BANK TREASURERS FOLLOW THE MONEY

U.S. banks reported another solid quarter of profits, with asset quality numbers remaining relatively stable. Their exposure to office commercial real estate remains a weak spot for them. Still, not a significant threat to their future financial performance, given that accounting for credit losses already incorporates a reserve for the life of their loan books under Current Expected Credit Loss. The story for 2025 so far remains unchanged, despite all the tariff drama and other uncertainties surrounding the Fed and its future independence.

Bank managers remain optimistic for their performance trends through the remainder of the year, regardless of whether the Fed decides to cut short-term rates this month, hold off to cut in Q4 2025, or not cut at all, and insist that their net interest margins remain as neutral as can be to any rate scenario. The latest open interest data from Eris Innovations, one of this newsletter’s corporate sponsors, shows that hedging activity increased in Q2 2025 and is already up in the first weeks of July. In addition to making it easier to hedge mortgage-backed securities with fair value hedges, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) announced last April that it is examining ways to modify cash flow hedge accounting rules.

However, bank bond portfolios remain significantly underwater for what was not hedged, as mortgage rates remain at levels not seen since 2001. Rate cuts would not necessarily help improve their fair value fortunes either, as they booked most of the portfolio on their balance sheets before the Fed's initial rate hike in March 2022. It would require a significant shift down the back end of the yield curve to bring their bonds anywhere near the par value at which they purchased them. Historically, they might have been optimistic that the Fed's rate cuts could help them out of the jam they are in. Still, when the Fed cut the Fed funds rate by 100 basis points in Q4 2024, the back end of the yield curve steepened, contrary to what happened before over several rate cycles spanning 40 years when the Fed lowered rates.

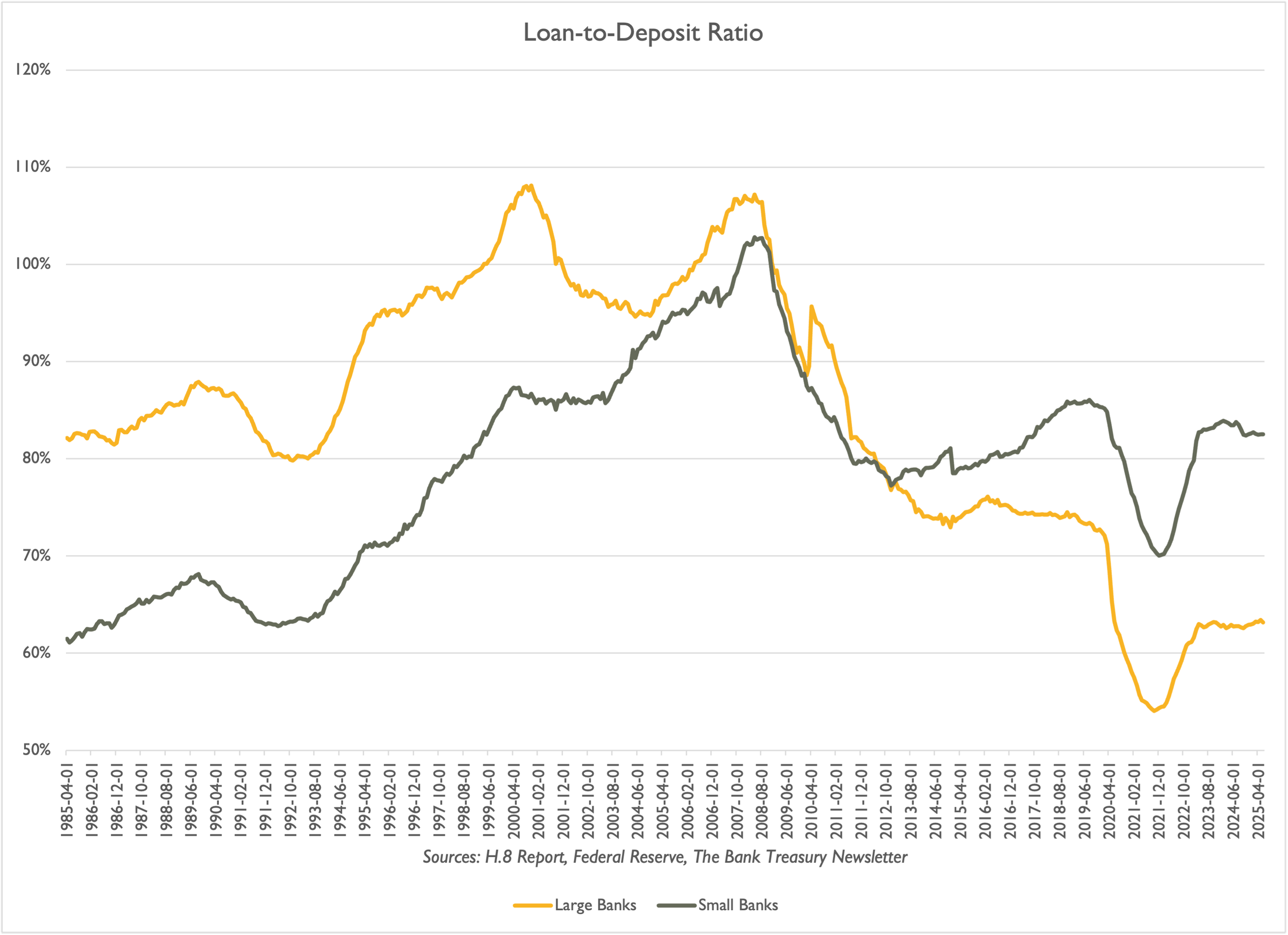

System-wide bank loans rose through the first seven months of the year to $11.7 trillion, or 70% of total deposits, compared to the 60% all-time historic low versus deposits they reached during the Covid pandemic and the 106% historic high they peaked at during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Deposits increased to $16.8 trillion, matching the level they peaked at just before the regional bank crisis in March 2023. Deposit growth notably defies the logic of quantitative tightening (QT), which should have exerted downward pressure on deposits as the System Open Market Account (SOMA) runs off based on a $5 billion monthly cap for Treasurys and a $35 billion monthly cap for Agency MBS, which continue to run off at half that rate. One reason might be that during QT 2, unlike QT 1, bank reserve deposits remain unchanged at $3.4 trillion, a level the Fed considers to be abundant. It pays banks 4.4% to keep their money with it overnight. Interest on reserve balances (IORB) is a controversial topic in Congress today, as the Fed’s cumulative negative Treasury remittances climbed to $235 billion this month, representing the difference between what the Fed earned from interest on its SOMA portfolio and other interest-earning assets it holds on its balance sheet compared to the interest it paid out to banks and money funds that fund it.

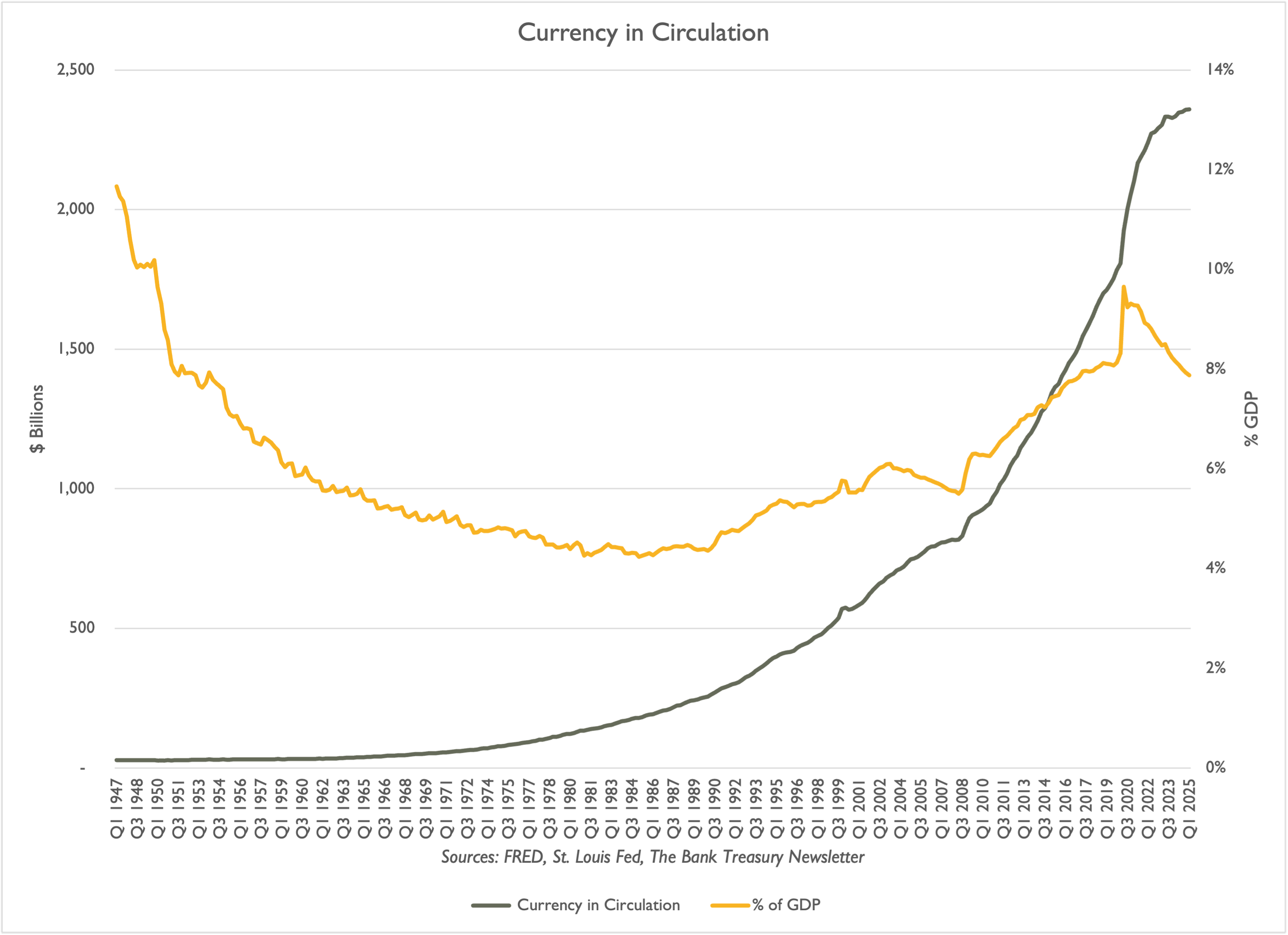

Bank treasurers have been concerned for some time about the digitalization trends in financial markets and their impact on the stability of their deposit franchises. They witnessed firsthand how destabilizing these trends can be during the regional bank crisis in March 2023. They are worried about the potential for disintermediation by stablecoins and other cryptocurrencies. Nevertheless, Congress passed the “Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins” (GENIUS) Act this month with bipartisan support. The law allows banks to issue stablecoins and, theoretically, opens the door to non-bank issuers to do the same, subject to authorization. Stablecoins must be pegged to the U.S. dollar and backed by short-term Treasury Bills or cash. The law will not allow the issuer to pay interest to stablecoin holders, which will make the cash banks convert into these coins equivalent to non-interest-bearing deposits, that they can use to fund interest-earning assets for their proprietary benefit until the stablecoin holders come to redeem them.

The Genius Act cannot take effect until the regulatory agencies, already tasked with revising existing bank regulations to make them more bank-friendly, write rules to implement it. They are under a deadline to complete them by January 2027. Meanwhile, given the connection between the cryptocurrency world and money laundering, the law requires the Treasury Secretary to solicit suggestions from the public within the next 30 days on how to protect the financial system from this threat. The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has three years to issue rulemaking based on those comments. Meanwhile, the Federal Housing Finance Administration (FHFA) last month instructed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to accept cryptocurrencies in loan assessments.

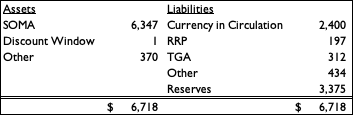

Bank CEOs were skeptical on analyst calls this month about the actual demand in the market for stablecoins, given their limited use case beyond using them to invest in other cryptocurrencies and the existing established choices for payments. Foreign remittances, for example, are another potential use case, but they would compete against already established networks, such as SWIFT. The new FedNow network volumes are soaring this year. Total stablecoins backed by US dollars amount to $250 billion, with most of these issued by two non-U.S. domiciled companies: Tether and Circle, the issuer of the US Dollar Coin (USDC). US paper money in circulation is ten times that, topping $2.4 trillion this month, and is also backed dollar for dollar against Treasurys. Euro paper money exceeds $1.5 trillion.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

Okay, class, please take your seats and settle down. Jay, I asked you to stop showing off those plans for the new Fed headquarters. Please put them away now. Don't you have enough trouble with that business already? Scotty, don't stick your tongue at Jay! You have your problems to deal with at Treasury, and there's also the potential for another Government shutdown this year.

Okay, then! Today’s class will cover accounting. No, no, none of that groaning, now. Accounting is essential in the bank treasury world. And, no, it is not dull. It might be a lot of things, but not that. If you do not believe me, just ask bank treasurers for an update on their bank’s underwater bond portfolio and see what happens. All I can tell you: don’t be alone with them when you do!

Because accounting is a very passionate topic in bank treasury circles, don’t roll your eyes, Jay. No, we will talk about interest rates another time. We cannot spend every newsletter obsessing over the timing of your next rate cut or whether your monetary policies are restrictive or irrelevant. Perhaps this time is different, and the economy, still going strong despite early signs in some of the latest inflation numbers of tariff-itis, may be immune to the laws of economics and business cycles.

Oh, hi, yes, Michelle, oh, I’m sorry, is it Mickey? Sorry. Congratulations on your new role as hall monitor for the banking industry. Sorry, vice-chair of supervision. Everyone is very proud of you, except perhaps Jay, who said he thought the job was essentially pointless, bordering on counterproductive. However, there is a time and a place for discussing bank regulations, and today is not that time or place. We can discuss that topic in a future newsletter.

You say it all comes back to bank supervision? I don’t necessarily disagree. But let’s not ignore the fact that you are losing all of your most experienced bank examiners and senior supervisors to early retirement, which only makes the job of Supervision that much more complicated than it already is. And even leaving aside your staffing issues, how can you supervise banks or devise ways to lessen Supervision’s burden on the industry if you do not first focus on accounting?

You can modify the enhanced supplementary leverage ratio for the largest banks to make it easier for them to buy Treasurys all you want, but first, you need to account for those Treasurys, Mickey. Leverage ratios are calculated based on call report data, which is based on generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) numbers, as if you did not know. Even if the FR 2052A data you collect from large complex banks is proprietary, non-public data, GAAP is ultimately the foundation for the constructed liquidity metrics.

What? Yes, that is true. There are differences between regulatory accounting principles (RAP) and GAAP, and there are some differences between the RAP as interpreted by the Fed, the OCC, the FDIC, and the NCUA. But those are exceptions. RAP is GAAP. Even the Fed’s balance sheet, which is subject to its own special accounting rules, is still tied to GAAP accounting.

Who can—excuse me, yes, Jamie, you wanted to say something about accounting? Yes, I promise there will be plenty of time at the end for you to vent about "crazy" accounting rules and why they do not matter. However, we must first learn about the standards and their significance before discussing why they are not relevant. Yes Brian? If we have time at the end of class, you can share with everyone how well your bank performed on the big test. Yes, Charlie, it's incredible how much progress your bank made last year. Who cannot be excited for you guys? And Jane, everyone is noticing the pop in the stock. Keep up the good work. However, let's first discuss accounting.

Accounting 101: It’s All About Balance

Accounting all comes down to two equations: assets equal liabilities plus equity, and debits equal credits. I know this is very basic, but these two equations describe entirely the economics associated with a financial transaction between two counterparties, and banking is all about financial transactions. Gazillions of transactions occur all the time at a bank, generating a multitude of debits and credits that result in assets, liabilities, and equity.

That is why banking is all about accounting. To understand what a bank does, it is essential to grasp the basics of accounting. Because when you think about it, other than a headquarters, some branches, and some staff, maybe a website, GAAP-based financial statements are pretty much the only tangible evidence that a bank even exists.

Double-entry accounting originated with the Venetians, whose merchants developed the concept during the Middle Ages to record their financial transactions accurately. Yes, Larry? No, your firm is not an exception. You follow double-entry accounting, but the large customer withdrawal you just had last quarter came out of your assets under management, not your balance sheet assets, because you have a custodial arrangement with your customers. You do not own the assets you manage, and therefore, the assets in your funds do not directly appear on your balance sheet. You look a little puzzled, but I promise we will revisit custodial accounting later when we discuss accounting for stablecoins, as there are some similarities between them.

However, the bottom line is that accounting is about what we own, whether it be a car, a house, an investment in a whole mortgage loan, a mortgage-backed security (MBS), or cash in a bank account. And it is about what we owe; whether it is the balance of an obligation that borrowers must repay their lenders, or the money banks must pay back to their depositors on demand, or to their FHLB, or their bondholders at maturity. It is about how the history of debits and credits has led to the assets, liabilities, and equity that we see today.

Equations encompass a variety of concepts, but one thing they all ultimately come down to is balance; any changes made to one side of the equal sign must always mirror the changes made to the other side. The right and left sides of a balance sheet are mirror images of each other. If you increase your total assets, by definition, you simultaneously increase some combination of your liabilities and equity to balance out that increase on the asset side of the equation. Or you reduce some other assets on your balance sheet to make room for the assets you grew. And the balance sheets for two counterparties to a financial transaction mirror each other; my debit is your credit, and your debit is my credit.

Because assets equal liabilities plus equity, and debits always balance out credits. Thus, if you have assets, you had to have either funded them at one point by taking in new deposits, borrowed from the FHLB, the Fed’s discount window, or taken advantage of some other borrowing. Otherwise, you would have had to raise fresh equity. Or the funding came from other assets you previously sold or that have matured. That is just arithmetic, accounting, and debits and credits.

The money to buy a bond or make a loan does not just come out of nowhere; it must come from somewhere, whether it is from another bank or a nonbank money fund. Money does not grow on trees, which is admittedly not entirely accurate, as the government prints it. Deficit spending contributes to the creation of new money regularly.

The government stimulus and the Fed’s Quantitative Easing during the Covid pandemic helped create money out of thin air, approximately $3 trillion of it, as measured by M2, which the Fed and the banking system distributed to the public. In the process, it generated its own set of mirror-image debits and credits that led to the $30 trillion of nominal GDP it reports today on one side of its ledger and the $36 trillion of Government debt it reports on the other side. This latter figure does not include the unfunded commitments it has for Social Security and Medicare, which, for government accounting purposes, are not recognized as part of the public debt.

Generally, money comes from somewhere. Bank treasurers make loans (assets) from deposit inflows (liabilities). There is a theory that they can also create money when they lend. It is a theory that warrants consideration, as bank treasurers recall that roughly $600 billion left the banking system in the wake of the SVB, Signature Bank, and First Republic failures, which depositors fleeing to safety transferred to money market funds. The deposit outflow could have crippled the banking system’s lending capacity. Instead, loans grew modestly in the second quarter of 2023. The small bank peer group in the Fed’s H.8 report, a group that bore the brunt of the deposit outflows, reported loans outstanding increased by $200 billion, to $4.4 trillion, in the year following the bank failures.

Of course, bank treasurers also turned to the FHLBs to help them cover their deposit outflows and fund their loan growth, which advanced them over $250 billion in the immediate wake of the crisis. However, whether bank treasurers obtained funding through making loans, FHLB advances, or found some other source of money on their balance sheets, the key point is that the money comes from somewhere and that debits and credits are always involved.

Measurable and Probable

You must be able to count on something to put on your balance sheet. Because double-entry accounting does not work unless everything that gets added to the balance sheet meets the definition of an asset, liability, or equity, and is measurable and reliable information. Assets are "probable future economic benefits obtained or controlled by a particular entity as a result of past transactions or events," to quote another accounting concept. Liabilities are a "present obligation of an entity to transfer an economic benefit."

Dirt might be precious, but unless you put it in a fancy bag with a colorful label and slap a price tag on it to sell at the farmer's market, it "ain't" worth—and you can complete the rest of that sentence. And more importantly, it is not an asset, leaving aside any sentimental value attached to it. I might owe you my life, but if you're like, "try to collect" when you ask for a favor in return, that debt of gratitude is no more my liability than your long-term receivable, in a strict GAAP accounting sense. I have nothing to credit, and you have nothing to debit. It is just business and accounting.

Debits on the left side of the balance sheet increase assets, while credits decrease them. Conversely, debits on the right side of the balance sheet reduce liabilities and equity, and credits increase them. Revenues generate credits in the equity account, improving the balance of retained earnings. Expenses generate debits and reduce retained earnings. Income recorded with an equity credit will always mirror a gain (a debit) on the asset side, and costs recorded in retained earnings with a debit to equity will always mirror a credit to payable liabilities.

And—I am sorry, who are you? Oh, hi Erik Thedéen, Governor of the Swedish central bank and the head of the Basel Committee for Bank Supervision. I assume you met Mickey. What was that? BCBS 239, "Principles for Effective Risk Data Aggregation and Risk Reporting," is critical. Thank you for mentioning that. If data is not reliable and accurate, GAAP does not work. Information technology and data infrastructure must be adequate; otherwise, bank treasurers have no way of utilizing them when they need to make decisions. During the financial crisis, they were not.

Without data, there are no debits and credits, assets, liabilities, and equity. Whether we are discussing accrual or fair value accounting, accounting for current expected credit losses, hedge accounting, or deferred tax accounting, it all comes down to debits and credits, assets, liabilities, and equity. Jonathan, you had your hand up. By the way, congratulations on your confirmation to the OCC.

Accounting For the Worst Bonds Any Bank Treasurer Has Bought Ever in Their Career

You want me to run through fair value and hedge accounting with the debits and credits so you can better understand why the U.S. banking industry’s fixed-rate assets are so underwater? And how does hedging with products such as our corporate sponsor Eris Innovation’s SOFR Swap futures contract impact the accounting for assets, liabilities, and equity? Well, Eris is probably better suited to run through the applicable accounting, but let’s start at the beginning with the first debits and credits.

In July 2020, when the average mortgage rate on a 30-year loan was 3%, bank treasurers purchased MBS bonds at par with the cash they held at the Fed in their reserve accounts, debiting their bond portfolios and crediting their reserve accounts. Their reserve account was where they had parked most of the surge in deposits they received during COVID-19 and the stimulus. They might have bought longer or shorter CMOs or Treasurys with the money. Still, whatever they decided to do, it was when interest rates across the yield curve were historically low, having been low since the GFC.

Consequently, any bond you bought back then was one of the lowest, if not the lowest-yielding bond, you had ever bought in your career. Bank treasurers were aware of this at the time. They described the debate raging in their head at the time about buying bonds with the reserves they had sitting at the Fed like this: on the one hand, sitting in cash and earning 10 basis points does nothing for my net interest margin (NIM) this quarter, and everyone hates me. On the other hand, buying MBS with a 3-handle coupon will weigh down NIMs for many more quarters to come, and everyone will still hate me.

The accounting was all straightforward. Bank treasurers credited the balance they had in their Federal Reserve account (the Fed simultaneously debited its reserve liability) and debited their bond account. The bond issuer, like Scotty here at Treasury, also simultaneously recorded the transaction as a credit to increase the government debt and a debit to increase its checking account balance at the Fed for the money raised in the offering. Less than two years later, the Fed went higher and faster than bank treasurers had ever imagined, to fight what Jay here said he thought was transitory inflation, but which four years later is still above its 2% target.

I hear you, Chris Waller, that you think it is time to cut now and that the persistent above-target inflation rate should not prevent a 25-basis-point cut. I think Kevin is in the same camp. Then again, do 25 basis points matter? And even if you do cut 25 basis points, are you sure that the back end of the yield curve will cooperate and come down, too? Because it increased in Q4 2024, the 30-year Treasury yield is now over 5%.

But let’s get back to Jay’s rate hikes in 2022-2023, which made every bank treasurer live to regret ever looking at bonds four years ago, which the accounting only made worse. The hikes cost bank treasurers 5-to-10 points of fair value against the original face value of the bonds they bought. Fixed-rate loans they made before the rate hikes also lost a significant amount of fair value, but GAAP only requires fair value for bonds, not for any other account on the balance sheet. Fair value only applies to bonds held in an available-for-sale (AFS) account, not to those held in a held-to-maturity (HTM) account.

To reflect only the fair value loss on their AFS bonds which is unrealized because bank treasurers hold on to the bonds, they record a credit against the carrying value of the asset and a debit split between Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI), a sub account under equity the value of which they report after-tax, and deferred tax assets, to record the unrealized benefit of the fair value loss on them. Then they need to remember to reverse the debits and credits with the deferred tax asset account as the bonds mature over time to par, assuming they recover the unrealized loss at maturity. Yes, I know, fair value accounting and tax accounting can be a nightmare for bank treasurers trying to keep all the debits and credits straight.

The rate hikes between March 2022 and July 2023, coupled with the sharp increase in mortgage rates, generated a lot of debits to bank AOCI accounts, so much so that, according to the FDIC’s data, AOCI fell to negative $333 billion at the end of June 2023, 18% of equity, adding back negative AOCI. I know the bankers with us today have all complained bitterly over the years that fair value accounting rules for bonds are lopsided accounting. The same interest rate price changes that impact their bonds also impact their loans and funding, but only bonds are subject to special treatment. How is that balanced?

And indeed, there is a lot of economic truth to what they are complaining about, best summed up in their economic value of equity (EVE) calculations, a regular obsession of bank treasurers who view the left side of their bank’s balance sheet as a hedge of its right side, ignoring timing differences. But accounting is not about economics. It is about rules, and the fact that depositors can and have pulled out all their money at par in the blink of an eye.

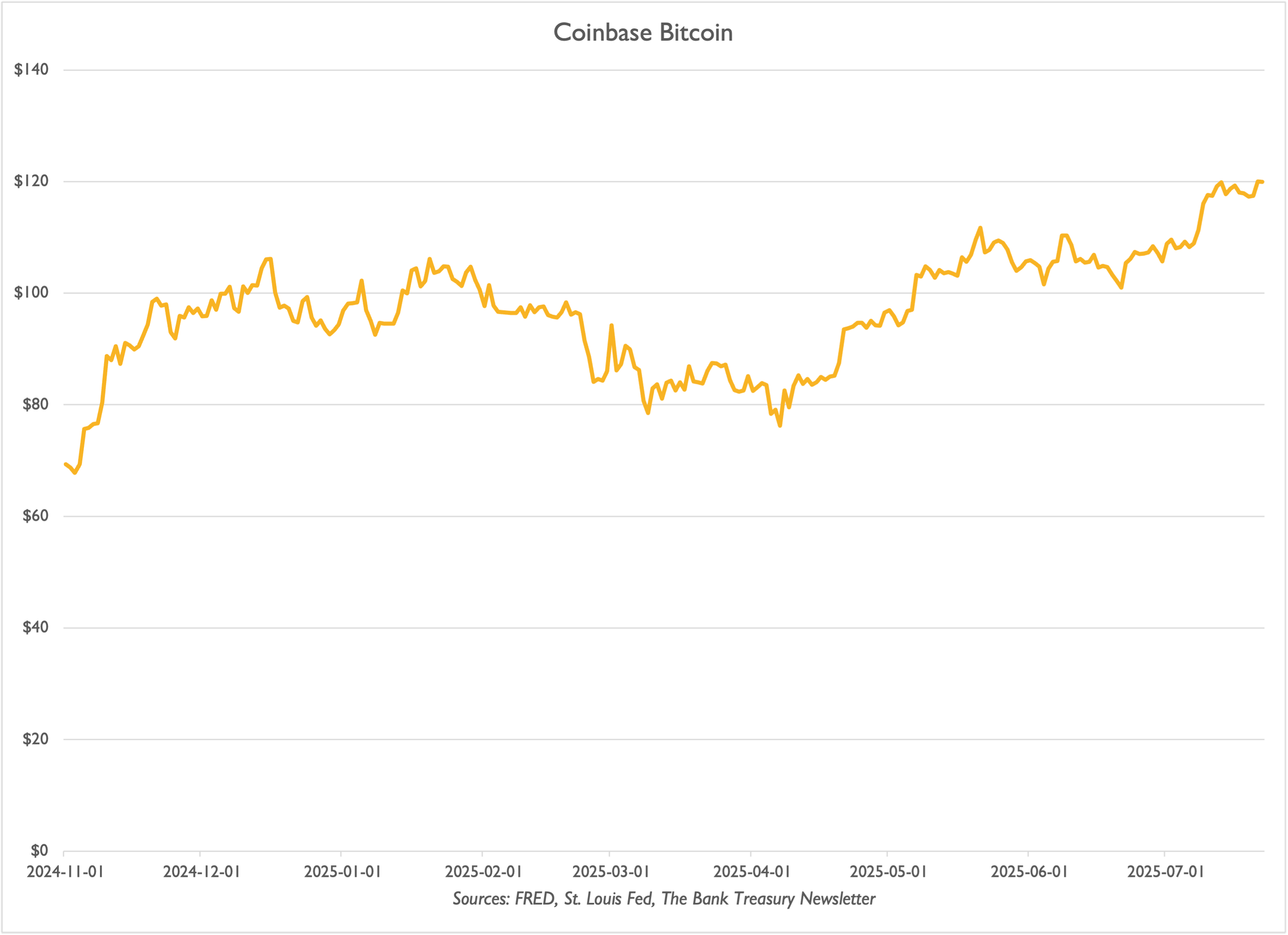

FedNow Q2 2025 settled payments totaled $246 billion, a five-fold increase over the volume in Q1 2025, which itself represented more than double the volume of the previous quarter. The average payment over the site increased from $37,099.02 in Q1 2025 to $115,331.82 this quarter, and the debits and credits associated with these payment flows occur at the blink of an eye, or officially, according to the website, in seconds. The speed at which deposits can be transferred to safety these days is one good reason why, lopsided accounting grumbles aside, bank deposits will never show up on bank balance sheets at any value other than their payoff value. Those are the rules.

Accounting is simply what the rules dictate. Even if the low-coupon MBS bonds bank treasurers still have stuffed away in their HTM portfolios and fixed rate commercial real estate loans on their books will be underperforming on their balance sheets and eating up shareholder value and tangible common equity used to fund them for a very long time, market value has no debit and credit consequences for any other asset or liability on bank balance sheets for purposes of current income but the bonds they hold in AFS or assets in any other held-for-sale account. Because if they want to sell assets before they mature, or at least have the option to do so, they must value them at fair value and bear the unrealized capital gains or losses. Those are the rules, the debits, and the credits.

Debits, Credits, and Derivative Hedge Accounting

Hedging involves associated debits and credits that bank treasurers neglect at their peril. A hedge is a financial transaction designed to mitigate the risk of loss on the balance sheet, whether in the bond portfolio, loan portfolio, deposits, or other funding sources. Thus, hedging involves something that you are trying to hedge and something that you are using to do the hedging.

There are also two types of hedges: fair value hedges and cash flow hedges. A fair value hedge hedges fixed rate financial instruments, and a cash flow hedge hedges floating rate financial instruments, synthetically converting fixed to float or float to fixed to the extent that the hedge tracks between 80% to 125% of the hedged instrument’s price change. It is called being highly effective.

Just like buying casualty insurance, buyers know that a catastrophe could occur and potentially cost them a significant amount of money if it does. Still, they do not know if the disaster will happen and, if it does, how severe it will be until it occurs. You might never have a catastrophe, in which case the annual premiums you spent to maintain the insurance policy were just a cost of doing business. Ultimately, you can never put a value on peace of mind, which is why it is not an accounting concept and why you do not show anything for it on the balance sheet unless you can quantify it.

Under GAAP accounting, you can only hedge with approved financial instruments, which are derivatives, including swaps and futures. Insurance is also a derivative product, worth conditional on what happens before it comes to term, whether a claim is made on it, and the only thing one can know about its value at any point in time before then is how much it is in or out of the money.

That is why the FASB wants all derivatives recorded at fair value, with debits and credits for unrealized gains and losses reflected in the income statement and recorded on the balance sheet as trading assets and liabilities. Because otherwise, there would be nothing to report on the balance sheet in a trading asset or liability account when banks trade them.

However, for hedging purposes, the rules are slightly different. Bank treasurers can take the fair value debits to equity and credits to assets, first pair them off and net them, before then reporting them in their income statements, and then only for the ineffective portion of the hedge, for price movements in the hedged financial instrument not covered by the derivative doing the hedging.

Which makes hedging complicated. Indeed, accounting rules do not make it easy to use hedge accounting because fair value debits and credits are not readily available when it comes to knowing about derivatives, the off-balance sheet financial instruments that do not appear on the balance sheet because their terminal value is conditional.

FASB is trying to make it easier to do both fair and cashflow hedging, rolling out multi-layered hedge accounting in 2023 to make fair value hedge accounting for MBS simpler and less hairy, and now looking to tweak the rules on cashflow hedging. But hedge accounting is complicated and not for the timid. There is just no two ways about it.

Combine fair value, hedge, and tax accounting, with deferred tax assets and liabilities, and then mix all that in with the complications involved when terminating a hedge early. Throw in some dangling debits and credits that can screw up the balance sheet and make the accounting complicated and expensive. It is easy to understand why many bank treasurers do not hedge interest rate risk in their balance sheets and did not hedge when they purchased the bonds in 2020 and 2021. So, that is the reason, Jonathan, why the industry is in the fair value jam it is in these days.

What was that, Scott? Oh, yes, that is true, Scott. Mistakes are not forever. Eventually, even the most extended MBS will pay off, just like the MBS sitting on Jay’s balance sheet in the SOMA portfolio, which might take a decade to run off at the rate it is going. Over time, the fair value loss will accrue back to par, converting the previous credits to the AFS into debits, and the earlier debits to AOCI into credits, which will increase equity and restore solvency. But not every bank treasurer has that kind of time.

Those deferred tax assets and liabilities will also need debiting and crediting; let’s not forget about them and avoid dangling debits and credits that will not balance forever. Of course, all bets are off if the issuer defaults. I suppose Scott, you would know more about that, given the substantial size of the Treasury’s refunding needs that you announced when you said that you expect to raise net new funding in Q3 2025 equal to $554 billion, a large chunk of it in Treasury Bills.

Balancing the Balance Sheets: Treasury, Fed, and the Public

The Treasury Bills that your Treasury department will issue to fund the deficit this year will create both an asset and a liability for the U.S. government, the debt a liability on the right side of the Federal government’s balance sheet, the cash raised through the auctions an asset on the left. You will keep the cash that you raise in the auctions at the Fed, which technically is the fiscal agent for the Treasury, in a special checking account managed on the right side of its balance sheet, also known as the Treasury General Account (TGA).

All the debt maturations, your timely interest payments, Social Security, Medicare, and every other government entitlement payment run through the TGA, each one a credit to the TGA. All the auction proceeds and tax receipts that flow in are credits for Jay, debits for you. And, yes, you are right, Scott, unlike the reserve deposits Jamie, Brian, Charlie, and Jane leave and the RRP, which Larry uses, Jay does not offer interest checking to the Treasury. But the TGA is not the main account on Jay’s balance sheet that really matters. It is just a topic of conversation because its balance is very volatile. Shutdowns, debt ceilings, tax filing deadlines, and a host of other variables impact it all the time.

Let’s look at some of the other line items on the Fed’s balance sheet that matter more than the TGA. You wanted to say something, Chris Waller, that I think you already said earlier this month when you visited the Dallas Fed?

“I know from teaching this topic over the years to my undergraduate students that unless you are an accountant or a banker, you would probably rather go to the dentist than listen to a speech about the Fed's balance sheet.”

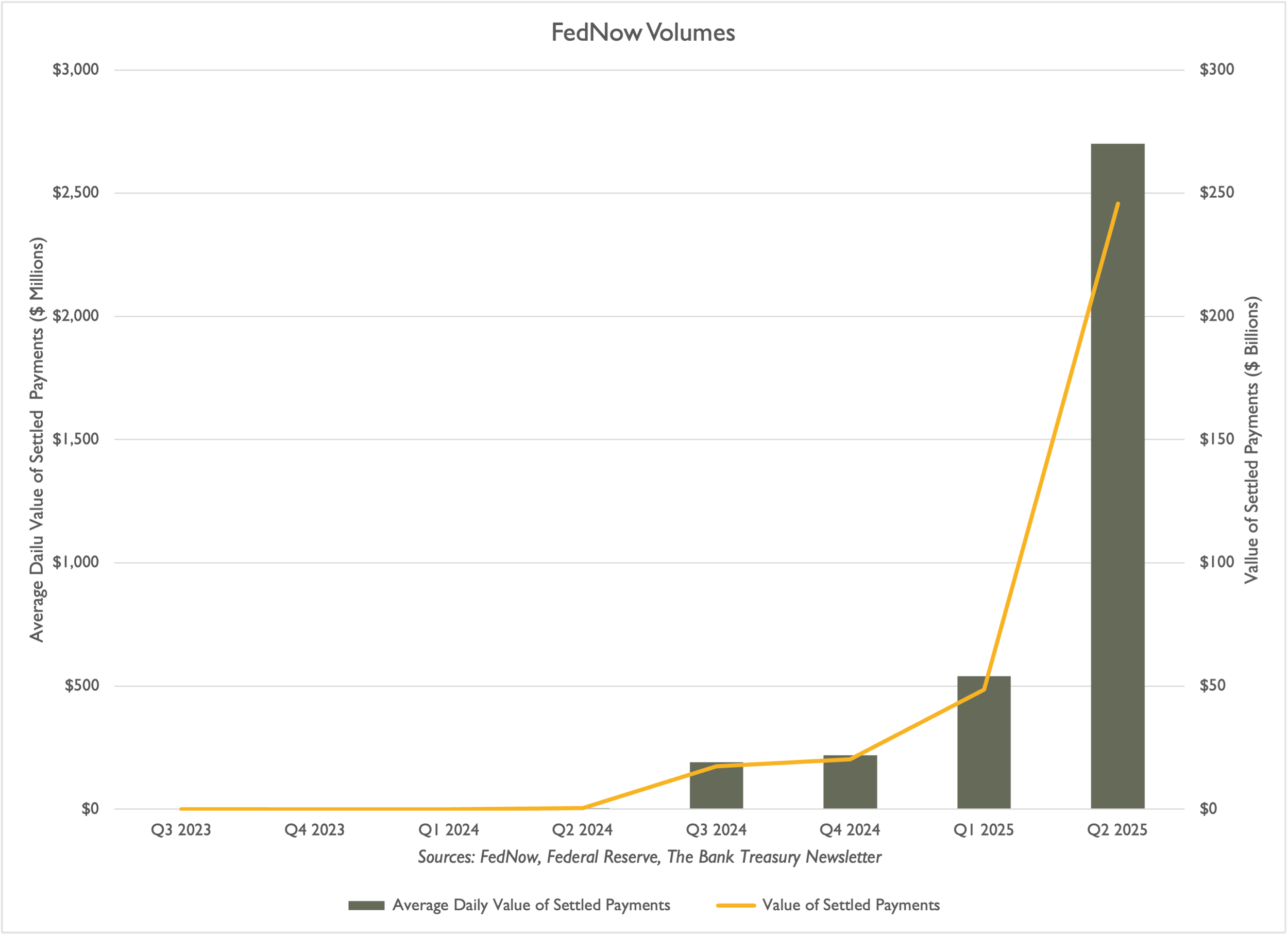

Thanks for those thoughts, but bank balance sheets and the Fed’s balance sheet are closely connected, given that bank treasurers are funding half of the Fed’s balance sheet. I am sorry, Ted, you said you want to ban Jay from paying Jamie, Brian, Jane, and Charlie interest on their money at the Fed? But that makes no accounting sense, Senator. Let’s look at a simple diagram of Jay’s balance sheet with some basic numbers that it reported this month (Figure 1) to see why the Fed’s balance sheet cannot go back to the size it was before Covid when its balance sheet equaled $4 trillion, much less the size it equaled before the GFC when it was under $1 trillion.

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Figure 1: The Fed’s Balance Sheet as of July 17, 2025

Sources: H.4 Report, Federal Reserve, The Bank Treasury Newsletter

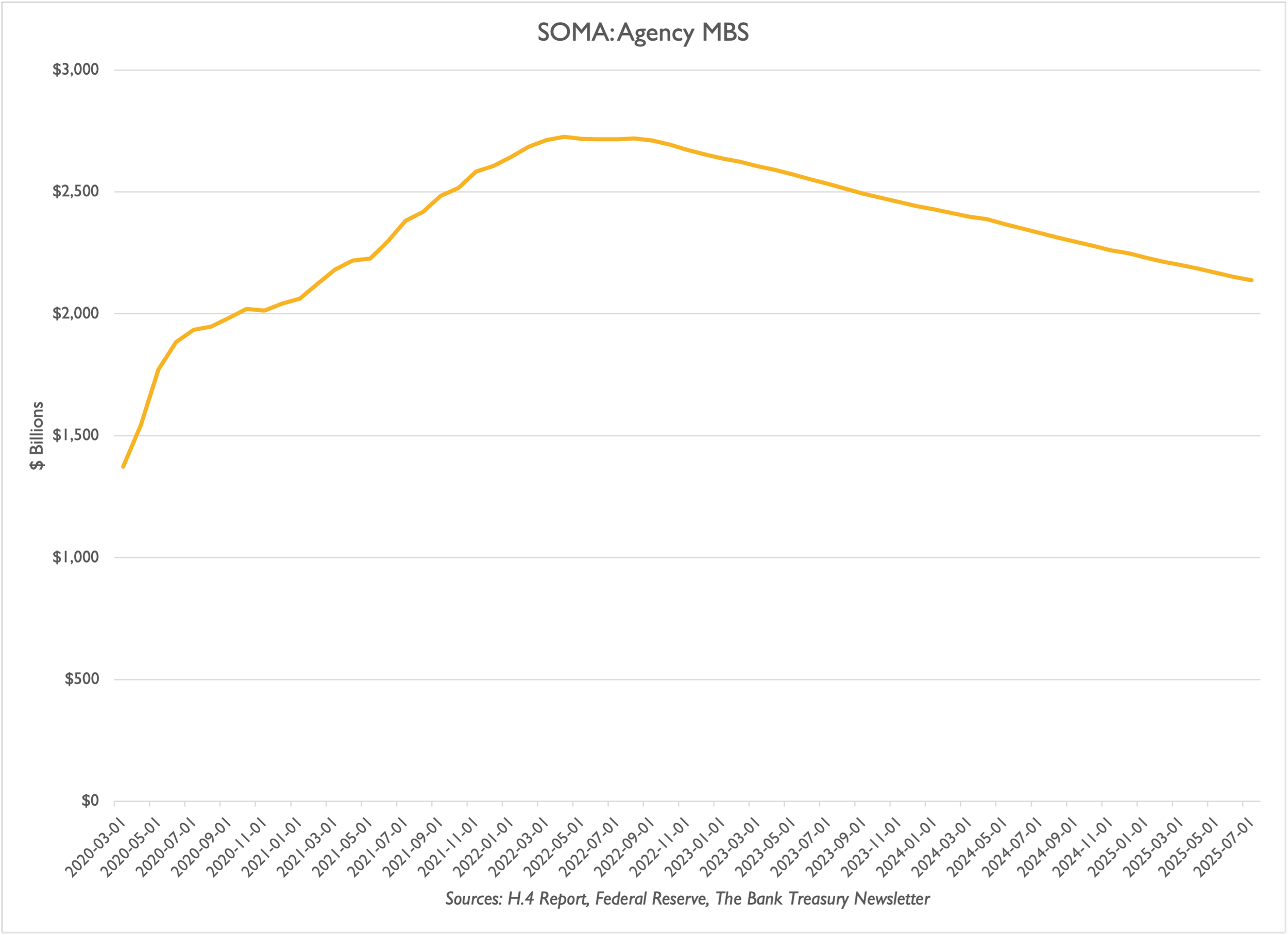

On the left, the Fed’s SOMA portfolio is virtually its entire total assets leaving aside the $7 billion balance in discount window loans, which includes a $1.4 billion balance in Paycheck Protection Program loans, the $11 billion in gold stock it keeps in its basement vault at the New York Fed, and an assorted list of other items including what the Fed estimates as $53 billion in coins lost and forgotten in someone’s cushion. Based on recent comments by Fed officials, the Fed likely plans to continue to let the size of its SOMA portfolio of Treasurys and Agency MBS run off at $5 billion and $35 billion per month, respectively. The Agency MBS portfolio, however, is running off at half that rate, for total monthly QT outflows equaling $20-$25 billion.

Every dollar of run-off is a credit to SOMA. The debit so far to balance that credit has hit the RRP, the balance of which is down to less than $0.2 trillion, but a few years ago, it was almost $2.4 trillion. Or it could balance credits to SOMA through debits to other assets, as it did in 2023 when it launched the Bank Term Funding Program on the left side of its balance sheet and grew it in early 2024 to $160 billion before it expired in March 2024 and then ran off in a flow of credits. One account that has not hit yet to balance the credits to SOMA is its reserve account, the balance of which has remained unchanged since the beginning of QT.

While the Fed shrinks its balance sheet, the public is busy picking up the slack, stepping up in the auctions and in the Agency MBS issuance to buy the new bonds that the Fed did not replace. The run-off credits to the Fed’s SOMA then mirror the debits to the public’s assets and credits to its deposit accounts. QT causes the public to withdraw cash from its bank accounts, which forces bank treasurers to withdraw reserve deposits or find some other account they have on their balance sheets to credit or debit to fund the outflow. As bank reserve balances are stable, this must mean that they found other accounts.

But if Ted was able to prevent Jay from paying interest to Jamie, Brian, Jane, and Charlie, there is a good chance that they would leave a lot less in their reserve account than they have sitting in it now. And the problem with that is that reserves, in addition to a bank treasurer’s highest quality liquid asset on the balance sheet, reserve deposits are also central to the payment system run through FedWire, which investors use to settle payments for the Treasurys they buy in the auctions and to settle trading.

The Treasury market would essentially grind to a halt, and the risk of financial panic would increase if the supply of reserves were not adequate, as it proved to be on September 15-16, 2019, when the SOFR rate jumped 3 points overnight to 5.25%. Indeed, research by the New York Fed showed that stresses in the overnight repo market are already showing up in the spread between repo and the Fed’s rate on the RRP.

Since the Fed has no idea where the line between abundant, ample, or just not adequate is, or has any confidence that if it did know where that line is right now, that line would stay in place, the Fed is committed to maintaining an abundant reserve policy and playing it safe. Abundant reserve policy means that it will maintain a supply of reserves well beyond demand, sufficient to insulate the prevailing effective Fed funds rate from slight changes in the balance. The Fed calls this reserve demand elasticity, which it tracks on the New York Fed’s website.

You want to make another point, Chris, why the Fed needs to pay interest on reserves?

“If reserves bear no interest, then commercial banks will have strong incentives to avoid holding a lot of reserves, and instead hold short-term, interest-bearing assets like Treasury bills. If banks managed their liquidity only by buying and selling Treasury securities, several banks selling Treasury securities at the same time could flood the market and put undesirable upward pressure on interest rates across the economy. An ample-reserves regime where we pay interest on reserves ensures that there are enough reserves in the banking system to avoid this kind of sell off in Treasury securities, helping to stabilize the financial system without any harm to banks or their customers.”

Thank you, Chris, and the ramifications of eliminating IORB do not stop there. To balance the balance sheet if a sizeable enough chunk of its reserves were to leave, the Fed would probably need to sell off some of its SOMA book, which would be the same as accelerating the pace of QT. Obviously, if the Fed still thinks its monetary policy is too restrictive, accelerating QT is probably not a great way to ease. The Fed could always force banks to keep their money in reserves by increasing required reserves from $0, the level it lowered it to in March 2020. Or it would need to find some other liability to credit to balance the debit outflow from the reserve balance.

And the fact is, like you said, Chris, paying interest to the banks and the money funds does not cost the Treasury anything.

“Whether the Fed or banks hold the Treasury securities, the Treasury is paying interest on its debt. And, if the Fed is holding the Treasury securities, then the interest payment from the Treasury to the Fed on the Treasury bills is matched with an interest payment from the Fed to banks on their reserves. So, paying interest on reserves is not creating any additional expense to the Treasury.”

Yes, but just for the record, the Fed still needs Treasury to make up the shortfall between what the Fed earns on SOMA and what it pays out in IORB and RRP. That creates its own set of debits and credits, which result in an odd liability on its balance sheet called “Negative Treasury Remittances” (NTR). The Fed reported this month that this liability equaled a cumulative negative $235 billion. A negative liability automatically adds to its reserve deposits, just as if the Fed were to suddenly turn around and revert to Quantitative Easing, thereby expanding SOMA. Last year, for example, the Fed reported interest income of $159 billion from its SOMA portfolio, and $227 billion interest expense, of which $186 billion went to pay banks for their reserves.

Currency in Demand: Hard Cash Versus Digital

After reserve deposits, currency in circulation is the second-largest liability on the Fed’s balance sheet. At $2.4 trillion, Federal Reserve notes —the paper money in your wallet —fund 36% of the SOMA portfolio. By law, the Fed’s SOMA Treasury holdings back the reserve notes in your wallet, which is one reason the Fed’s balance sheet will never shrink back to its size before the GFC and Quantitative Easing. In July 2005, for example, the Fed’s entire balance sheet totaled $796 billion, virtually all of which consisted of a portfolio of Treasuries on the left side and paper money on the right. Reserve deposits equaled just $12 billion.

Like the TGA, the Fed does not pay interest to holders of paper currency. Therefore, if the Fed could return to funding its Treasury portfolio solely with paper money, the Fed would become a highly lucrative source of revenue for the Treasury, especially when raising rates. However, unlike any other liability on its balance sheet, currency in circulation simply grows. Sometimes, as is the case now, growth is glacial at 1% per year. At other times, as in 2020, growth is explosive. Sometimes it is just steady, as in the years after the GFC, when currency increased from $0.8 trillion to $1.8 trillion on the eve of COVID.

Chris, you had something to say about the TGA and currency in circulation?

“An important point that applies to both currency and the TGA is that the Federal Reserve does not have control over the size of these liabilities and hasn't been responsible for their sharp increases. Together, they represent about $3 trillion of our $6.7 trillion balance sheet, or roughly 10 percent of nominal gross domestic product. So, the size of the Fed's balance sheet, which is now about 22 percent of nominal GDP, is nearly half accounted for by these two liabilities that are not under the Fed's control. Those who argue that the Fed could go back to 2007, when its total balance sheet was 6 percent of GDP, fail to recognize that these two factors make it impossible.”

It is hard to imagine, you are right. Of course, if the Fed could convince the public that holding more paper money was desirable, maybe by forcing the economy into a recession and deflation, it could issue more and finance its balance sheet with less reserve deposits. It could keep rates at 0% or even figure out a way to turn rates negative. Bank treasurers could hold cash in their vaults.

However, vault cash is a non-interest-earning asset for a bank and does not count as High-Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA), contrary to terms like ready cash, hard cash, and cash on the barrelhead, which may lead one to believe otherwise. Maybe Mickey could consider adjusting the leverage rate for vault cash after she finishes fixing the capital cost for holding Treasurys. However, hard cash is generally a tough sell to the public, which often wants more cash when it wants it and less when it does not.

A central bank digital currency, which the Fed studied before the current Administration banned it through executive action and which the Anti-CBDC Surveillance State Act would prohibit by law, would not have paid interest to holders either. As an instant payment method, it would have competed in a space already dominated by credit cards on the consumer side, with digital payments still a distant second choice. FedNow is growing in popularity, but more generally, CBDCs are just not a big topic in the US, where the public’s confidence in the US Dollar, despite the bleeding deficit and unfunded commitments, remains unshaken.

A central bank digital currency, which the Fed studied before the current Administration banned it through executive action and which the Anti-CBDC Surveillance State Act would prohibit by law, would not have paid interest to holders either. As an instant payment method, it would have competed in a space already dominated by credit cards on the consumer side, with digital payments still a distant second choice. FedNow is growing in popularity, but more generally, CBDCs are just not a big topic in the US, where the public’s confidence in the US Dollar, despite the bleeding deficit and unfunded commitments, remains unshaken.

Crypto Currency and Accounting for Stablecoins

Like paper money, the new GENIUS Act bans stablecoin issuers from paying interest and requires them to back their coins dollar for dollar with Treasurys. However, the demand for cryptocurrencies, including stablecoins, is not driven by interest income. Holding cryptocurrencies is speculative unless you live in a country such as El Salvador, where confidence in the country’s national currency was so low that it adopted the U.S. dollar as its national currency in 2001 and made Bitcoin legal tender in 2021, only to reverse course this year under pressure from the IMF. The main use case for stablecoins is to invest in other cryptocurrencies, which, like them, operate on blockchain technology.

Yes, Jamie, you had a comment this month during your call about stablecoins?

“I don't know why you'd want a stablecoin as opposed to just a payment.”

A good question. One reason your customers are interested in stablecoins is the push by the Administration. Last month, the FHFA ordered Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to accept cryptocurrencies as part of the mortgage application process. The order did not specify whether this included only stablecoins or other cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin. However, you are right to question how stablecoins solve the problem of payments in the U.S., a conclusion reached by members of the Fed’s Federal Advisory Council last May,

“Council members opined that stablecoins offer no significant advantages when compared to real-time 24/7/365 U.S. payment solutions, specifically Real-Time Payments (RTP) and FedNow. These existing systems are capable of matching stablecoins in terms of transaction speed and finality for U.S. payments. In addition, these systems are available at a low cost, and in some cases—such as with Zelle—are provided free of charge to consumers. In contrast, transactions involving stablecoins on a public blockchain incur fees, even when both the sender and recipient are located within the United States. Furthermore, customers may be subject to fees for converting between stablecoins and fiat currencies.”

Issuing a stablecoin is not exactly going to be easy for banks or non-banks. Going by the 2022 guidance from the New York State Department of Financial Services to stablecoin issuers which remains the most comprehensive guidance on the subject by any state banking department, and was incorporated by Congress in the GENIUS Act, an issuer must meet a set of requirements to validate its claim that the coin is fully backed by U.S. dollars or the equivalent in short-term Treasurys dollar for dollar in a reserve fund.

Demonstrating that it can meet timely redemption (less than 48 hours) requests to convert stablecoins back into U.S. dollars, it must segregate the assets in the reserve from the rest of its assets and obtain a monthly attestation by a registered third-party CPA that it is meeting the reserve requirements for the coin are some of those requirements. In many respects, managing a reserve fund to back stablecoin issuance would be nothing new for bank treasurers, who already follow somewhat similar procedures for managing the collateral they use to borrow advances from the FHLBs.

Meeting them and not paying interest or distributing income to the coin holder, the SEC ruled last April that the stablecoins issued by a bank are not even debt securities, they are just cash converted into a digital currency, a debit to its cash account and a credit to a noninterest bearing deposit account where the coin buyer left the money with the bank stablecoin issuer. Thus, in some sense, stablecoins are another form of digitalized deposit. However, if you do issue them, there are significant opportunities to generate some money. Jane, did you have a comment to make?

“Yeah, look, digital assets are the next evolution in the broader digitization of, payments, financing and liquidity. Ultimately, what we care about is what our clients want and how do we meet that need…we're exploring reserve management for stablecoins, the on- and off-ramps from cash and coin, backwards and forwards. We are looking at the issuance of a stablecoin…and then also providing custodial solutions for crypto assets. So, this is a good opportunity for us.”

Indeed, as Chris, you summed up those opportunities in stablecoins, and why they could represent a more profitable non-interest-bearing deposit than the traditional form on bank balance sheets,

“To date, most stablecoin issuers appear to generate revenue primarily by earning higher returns on their reserve assets than they incur in expenses. They issue a zero-interest liability and use the proceeds to acquire interest earning assets, thereby profiting from the spread. As with bank deposits, the interest rate environment will have a significant effect on the profitability of firms issuing stablecoins. Higher interest rates generally mean higher rates of return on reserve assets, which generates revenue for the issuer. However, higher interest rates also have the potential to make noninterest-bearing assets less attractive for consumers to hold. That said, users who hold stablecoins as an accessible, safe store of U.S. dollar denominated value may not be particularly sensitive to the interest rate environment, a phenomenon we already see today with some holders of physical U.S. dollars.”

Whether stablecoins take off due to legislation such as the GENIUS Act remains to be seen. Outstanding coins equal just $250 billion, with two of them, Tether and USDC, accounting for most of the issuance. Neither is a bank, and together they account for 80% of the total stablecoins outstanding. Tether, the largest issuer, is headquartered in El Salvador. Moreover, the use cases beyond crypto investment remain limited. It may help with foreign exchange, where stablecoins could be a cheaper way to make international B2B payments; however, the jury is still out. It might help people who do not have access to a bank account pay their bills, but the costs of using crypto to date have not been cheap.

There are also risks to the stability of the financial system, even with the dollar's backing behind stablecoins. There is always the concern of money laundering to worry about, which cryptocurrencies naturally seem to facilitate. FINCEN has three years to implement rules to protect the nation's financial system.

Tied to Treasuries, if the public's take-up increases, it could lead to higher demand for Treasuries as a stablecoin reserve. And stablecoins may not be so stable if every coin holder suddenly demands redemption and forces a massive fire sale of Treasurys to meet it. And, as Mickey must be learning, it helps to have some experienced bank supervisors working for the agencies because, as she knows, there is no guarantee that legislation or regulation can effectively control foreign stablecoin activities, including non-U.S. issuers of stablecoins such as Tether, without them.

And even if an issuer cannot pay interest on the cash it converts into stablecoins, there is nothing in the legislation that would necessarily prevent them from offering reward points to holders and creating competition that way. They probably cannot offer cash rebates, but the IRS does not consider reward points taxable income. In some ways, reward points offered to stablecoin owners might be like when banks used to give away toaster ovens to people for opening a deposit account with them. They might not even have to worry about any accounting involved until and if they need to pay the rewards as a rebate.

Okay class. I hope you all see that accounting is not dull and that, even though accounting for fair value, hedging, the Fed’s balance sheet, and stablecoins are complicated topics, remembering that what goes on the left equals what goes on the right helps make sense of them. One thing you can always count on is that your debits will always equal your credits. Class dismissed.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2025, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief

This Month’s Chart Deck

There is still too much money in the financial system. The Fed’s supply of paper money, Federal Reserve notes, topped $2.4 trillion this month, which equals 8% of nominal U.S. GDP (Slide 1), a little less than two percentage points below where it peaked during Covid and the Federal stimulus, but still well above the ratio to GDP which prevailed for most of the last six decades. At the margin, a dollar increase in currency in circulation reduces bank reserve deposits by one dollar. While paper money increased, the passage of the GENIUS Act led to a rally in the price of Bitcoin, which topped over $120,000 for the first time (Slide 2).

Whether dollar-backed stablecoins will succeed as a viable digital electronic payment method remains a question, but the latest FedNow volume data would seem to demonstrate the business use case for digital payment services, as payment volume reached $250 billion last quarter (Slide 3), five times the volume in Q1 2025. FedNow caps the value at $100,000 for a single payment over the network, but banks on the network have the option to allow their customers to make payments up to $1 million. Last quarter, the average single payment over FedNow was $115,332 (Slide 4).

The Fed’s QT caps run-off from its Agency MBS portfolio at $35 billion per month, but given that much of the portfolio was purchased just before the Fed began to hike rates in March 2022, its principal paydowns are down and pacing at roughly $15 billion per month, which at this rate will take years before the portfolio’s size returns to the level it stood at before the Fed began QE in 2020 as a response to the Covid epidemic (Slide 5). Monthly run-off from its Treasury SOMA portfolio remains capped at just $5 billion. Since QT began in July 2022, the Treasury SOMA portfolio balance has decreased to $5.2 trillion, down from a peak of $6.7 trillion. Commercial banks added $171 billion to their Treasury holdings (Slide 6) during that period.

Before the Global Financial Crisis, the Treasury General Account (TGA) balance never exceeded $5 billion to $ 6 billion on any given day. The Treasury’s checking account balance at the Fed became a very different affair as Government shutdowns and debt ceiling drama became more the norm in the process of funding the Federal Government (Slide 7) and preventing it from defaulting.

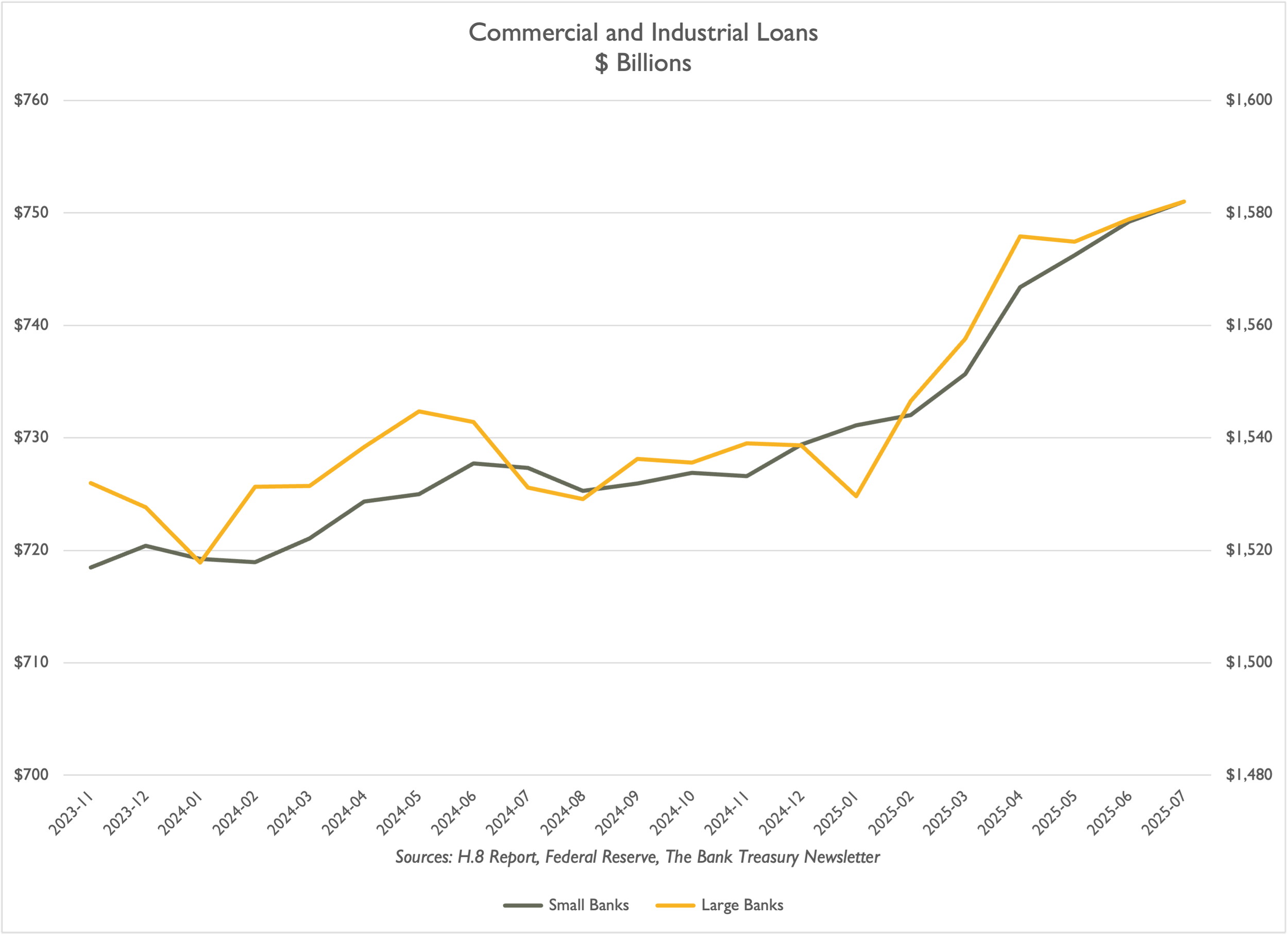

And despite QT and what the Fed believes is a restrictive monetary policy, loan and deposit growth have grown proportionally since June 2023 when the Fed raised rates for the last time (Slide 8), causing loan to deposit ratios for large and small banks to hold steady at 60% and 70%, respectively. Commercial and industrial loan growth drove overall loan growth (Slide 9), gaining momentum this year, which may be a sign of emerging animal spirits. On the other hand, the consumer’s discretionary spending could be weakening, a warning to be cautious. (Slide 10).

US Economy Powered By Cash

Bitcoin GENIUS Rally

FedNow Takes Off

FedNow Payments Soared Last Quarter

Fed’s MBS Bleeding Off Below Its Monthly Cap

Will Banks Buy More Treasurys If SLR Gets “Fixed?”

TGA Volatility: A Post GFC Phenomenon

Loan Growth And Deposit Growth In Synch

C&I Loans Feel Animal Spirits

Discretionary Spending Slower Since 2022