BANK TREASURERS CAN’T FLOAT FOREVER

The “Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins” (GENIUS) Act, which was passed into law last month, established a basic framework to incorporate stablecoins into the payment system. It makes the Treasury, Fed, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) responsible for approving the issuance of a stablecoin, which opens the door for U.S. banks, potentially non-U.S. institutions, and even fintechs to issue them. Having a bank charter is an unstated but de facto minimum requirement to get their approval. Thus, since the end of May, there are now six pending applications by fintech firms with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) for a special fiduciary powers trust charter. Notably, this month, the state of Wyoming issued a U.S. dollar-backed stablecoin. Notably, the state will direct the interest earned on the reserve backing its Frontier Stable Token to support the Wyoming School Foundation fund. If a bank were the issuer, it would capture 100% of the interest income for its shareholders.

A trust charter comes with less stringent regulations than a traditional commercial bank charter. Still, if the OCC grants them to fintechs, they will automatically have a master reserve account at the Fed, the same as any other commercial bank. It would be a significant encroachment on banking territory in the payment space since payments ultimately come down to moving reserve deposits from one bank’s account at the Fed to another. More generally, the community bankers worry that stablecoins will lead to fewer deposits in the system and reduce their capacity to make loans.

Stablecoins are just part of a growing trend towards instant payments, a trend which saw check-writing fall almost entirely out of favor with both households and businesses over the last few decades, but especially since the onset of the pandemic, as they paid 19% of their non-cash payments with a paper check in 2020 compared to just 7% of their payments in 2024. The U.S. government will no longer make disbursements or receive payments with paper checks at the end of next month. Businesses of all sizes, from large global corporations to tiny community-based companies, are telling their bankers that they want instant payments, which they regard as potentially cheaper to use compared to other payment methods and easier on cash flow management.

For example, the Fed’s two-year-old instant payment service (FedNow) reported a significant surge in payment activity since the new year and especially in the last quarter, with volume up to a record $246 billion, compared to $49 billion in Q1 2025. Real Time Payments (RTP), another instant payment competitor, run by the Clearing House, also reported a volume surge last quarter, reaching $481 billion. FedNow permits single payments up to $1 million, and RTP permits payments up to $10 million, which means that the main use case for stablecoins will involve much larger payments. Cross-border payment flows, which U.S. banks dominate, could be one major use case for stablecoins, and could disrupt global revenues from that business, which last year topped over $200 billion.

Theoretically, there is no reason consumers might not use them one day for small value payments, except that they like their credit cards and reward points, and even if stablecoins could offer points, unless there were a specific advantage to using them, it is hard to see opportunities for much take-up. One thing that stablecoins cannot do that interest-bearing deposits can is pay interest to depositors before their banks ultimately debit their accounts for their purchases. Stablecoin owners, on the other hand, probably do not focus on earning anything from them, other than their utility as a means of payment. They are probably not very bothered that the issuer pockets the interest income on the coin until the token holder goes to cash it.

Notably, while both FedNow and RTP operate 24/7, FedWire, which handles most of the clearing for securities transactions, is still closed overnight and on the weekends, as is the rest of the capital markets. A proposal by the Fed last year to expand FedWire to 22x7 remains undecided, and it has not provided any updates on when it would. The conflict between the shorter hours when the capital markets are open and an instant payment system operating 24x7 means that bank treasurers with customers which use instant payments must manage a larger mix of demand deposits in their deposit accounts, but also more High-Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) on their balance sheet than they would otherwise to handle potential cash outflows when the capital markets are not open.

A higher mix of low-yielding HQLA cuts their balance sheet capacity to make loans, constricts their net interest margin, and dilutes their interest income. It also might encourage riskier lending with the lending capacity they have left, as experience with other payment systems in different countries suggests can happen.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

If you are like most of the bank treasurers who talk to our editors these days, you probably think that the stablecoin hoopla is a fad, a distraction from what you are thinking about right now. We hear you. Even the Fed does not think crypto is an issue worth dedicating a whole special group to supervise it anymore.

What you want to know is what the Fed going to do at its next meeting (probably cut, though who knows with the inflation numbers that have been coming out and ongoing tariff uncertainty) and what cutting 25 or maybe 50 basis points will do to the yield curve assuming inflation does not get back to 2% by then (probably cause the back end to steepen and lead to higher mortgage rates). Or maybe you just want to talk about how the economic data seems increasingly unreliable and suspicious, and what that means for a bunch of Fed officials who say their monetary policy decisions are data dependent. Or maybe you just want to complain that everything with numbers has been weird ever since the pandemic.

But you got it all wrong!

This crypto business and the GENIUS Act that Congress passed last month are about more than just a scam, more than just a waste of your time, and more than solutions in search of a problem that will end up opening the door for money launderers and other criminals to corrupt the payment system. Maybe they are that, too, but stablecoins are still worth your attention because the opportunities and risks associated with stablecoins are significant. Stablecoins are more than just a new cryptocurrency to add to the collection of other cryptocurrencies to which you generally pay no mind, like Bitcoin, Ethereum, USDC, DOGE, and others you worry are going to all come crashing down one day. Hopefully not on you, dear subscriber.

And, besides, stablecoins are a cool hot topic these days, not to mention super interesting. Who wouldn’t want to read all about their potential impact on financial stability, and the future of all civilization, or at least the bank treasury world as we currently know it, while soaking up the last days of summer, floating in a swimming pool? After all, the only pools you will see when you get back to the office next month are the football pools, and during the year, you never have the time to take your floating days anyway. So, do it now!

But just so as not to bury the lead for this month’s edition of the newsletter any longer, we ask our readers to remember the number quadrillion. A quadrillion is a number your editor-in-chief readily admits never having heard come up before in polite conversations with our subscribers. It is a number so eye-goggling that he also admits to googling it when he encountered it in researching this month’s newsletter to make sure itwasa real word. And it is, writtenasthe number 1 followed by fifteen 0s. Okay, remember this, and we will come back to it in a hot minute.

What’s A Stablecoin Again?

But before we do, just to review the basics (and please see last month’s newsletter for additional thoughts on the accounting), a stablecoin is a digital currency that moves around between counterparties using that distributed ledger technology you heard about that Bitcoin uses with Blockchain. Which means now you have it, and in the next instant, I have it, and there is no question about title transfer or ownership rights to the coin because that is the whole idea behind distributed ledgers.

Everyone sings from the same hymnal; they see the exact page numbers and line items. There is nothing better in the universe for establishing that I paid you and you received payment, provided everyone first agrees on which edition of the hymnal we are using at this moment. Unfortunately, that might take a little time, given that when people talk about distributed ledgers, they mean distributed, like having computers geographically located around the world, literally all running the same algorithms simultaneously.

Under the law that Congress passed last month, a stablecoin is always backed 100% by a fiat currency that a third-party custodian manages. It is non-interest-bearing, which makes it the economic equivalent of a dollar bill, and not insured by the FDIC. These were key features the banking industry pressed for with the legislation when Congress was crafting it this year, to save the entire industry’s untimely mass disintermediation and to try to discourage their deposit franchises from self-deportation into the digital void.

Bank treasurers fear that their depositors, if offered the choice, will choose to own a digital deposit coin instead of a traditional deposit account. With stablecoins in the picture, they worry for the stability of their core deposits, their ability to profit from rate cycles, or to manage net interest spreads. They worry about the whole asset-liability management approach with stablecoins.

They believe they will disintermediate themand see them as no different a threat to their deposit franchises than the old central bank digital currency idea that theFed gave up on last year,and which the current Administration then banned earlier this year in anexecutive order. Even with all the safety features Congress put in the GENIUS Act, considered, bank treasurers are still very worried that deposit tokenswill be the death of commercial banking.

But What Threat Do Stablecoins Really Pose?

In your editor-in-chief’s view, it is hard to understand bank treasurer fears over stablecoins. Typically, the public does not like to carry cash if it can help it, unless the world is coming to an end, and even then, the average household may keep a few hundred dollars in a sock drawer in case of a zombie attack. It is not like people will withdraw their life’s savings to hold in a non-interest-earning, non-FDIC guaranteed stablecoin just because stablecoins are cool.

If that were true, what are deposit wars all about? Bank treasurers are not fighting wars over toaster ovens for account openings, and you guys do not even give those out anymore, even if they were once worth fighting over. Yes, depositors do move accounts if they are annoyed enough, but usually it is because they are sick and tired of having their bank rip their eyes out with fees and way off-market rates.

People who want to hold a stablecoin are not interested in a rate. They want a stablecoin to make a payment in a hard, trustworthy currency like a US dollar that can be denominated in any amount they want, even a quadrillion if they so choose, and which they can instantly transfer to someone else’s account in a flash using blockchain or some other distributed ledger system. That is the beauty of a stablecoin.

But most economically inclined participants in the financial system who keep bank accounts are not especially interested in how quickly the money in their deposit accounts can transfer to someone else’s account. Rates, security, ease of access, and FDIC insurance probably are higher up on their list of wants. And as far as retail payments are concerned, credit cards remain the dominant retail payment method of choice because they are effective for making purchases and come with reward points. Plus, you do not have to pay the credit card bill right away; you can wait at least until the end of the monthly statement period.

Maybe stablecoin issuers could one day offer reward points, too, but ultimately, there must be a benefit to switching from credit cards to stablecoins. Even if it might cost less to make an instant payment using a stablecoin instead of whipping out a card and tapping it on the card reader, the one thing about payments that people understand all too well is the hidden fees. There are always fees that no one thinks to count in their margins. Stablecoin savings could be a big mirage when you think about the costs one could get charged to convert fiat currency into stablecoins and then turn them back into fiat currency.

Stablecoins are not an investment; they are cash, and money managers do not get paid to sit in cash, even when the Fed pays the highest rate on the Treasury yield curve in the overnight, credit spreads are tight, and investments have more risk than rewards. They might want to use a stablecoin for trade settlement, and there is significant interest in tokenization for such applications. But once the trade settles, what would the holder do with a stablecoin other than turn it back into a bank deposit or use it to buy another investment that ultimately brings funds right back into the banking system?

And if they do not get paid by their clients to sit in cash, they certainly will not want them to sit in stablecoins, which make them no money and might even cost them something for storage, like the fees the Fed charges to store gold in its vault on top of all the other expenses they might incur. At least gold is an inflation hedge. And even went up for a change and made investors a lot of money in the last year.

Stablecoins are not even inflation-protected, much less an inflation hedge! No matter what happens in financial markets, their price will never change and never correlate with changes in any other financial asset because they are stable! Get it? A stablecoin will never be worth anything other than its par value, or at least holders better hope so. Past runs on stablecoins have not ended very well when doubts arose about the stability of a stablecoin’s off-ramp plans to convert back into the cash that backs them.

Even with the protections built into stablecoins with the GENIUS act, including that the reserve consists of dollars and Treasury Bills that a third party manages, there is no guarantee you can count on instantly converting your stablecoin back into a fiat currency in a crunch time. Bad things can happen, as a business already in the stablecoin issuance business conceded in its June 2025 securities registrant statement filing,

“Privately issued stablecoins may be subject to the risk of significant and concentrated redemption requests, even when they are fully reserved with high quality liquid assets such as cash and short-dated U.S. government obligations…in extreme cases, the market for the short-dated U.S. government obligations held by the…Reserve Fund might not be sufficiently liquid…to liquidate them in a way that allows us to meet redemption demands in a timely manner, which could potentially lead to redemption delays.”

Stablecoins entail a set of operational risks for both the issuer and the receiver, as any new payment system might create. There could be a bug in the computer code, the third-party reserve manager could suffer a security breach, or there may be a problem with the distributed ledger system, a process gap, or human error. There are money laundering and fraud issues to worry about with stablecoins, where money moves in a blink and is impossible to recall. What seems at first glance to be a foolproof method to make a payment can end up going bad just like any other payment system.

The only reason why anyone in their right mind would want to own some stablecoins right now is because they need dollars and they need to move them in a second. You want dollars if you live in another country with high inflation, and you do not trust the stability of your government. Or you want to keep a digital version of the dollar as a ready source to invest in cryptos like Bitcoin that do go up and down in price, or to make an instant payment. Cross-border payments, as Fed Governor Waller highlighted when he spoke about them earlier this year, are another good use case worth exploring.

Businesses keep operational deposits that are part of the partnership that they maintain with their business banker, and some of those deposits could end up in a stablecoin. But only if a stablecoin offered them a faster, more efficient way to pay their bills and payroll than they already have with services including Automated Clearing House (ACH), same-day ACH, wire transfer, RPT (run by the Clearing House), and FedNow (run by the Fed).

Both RPT and FedNow are instantaneous payment systems, and FedNow allows payments up to $1 million, and RPT now accepts payments up to $10 million. Volume on both services has soared this past year, with RPT reaching $481 billion in transactions in Q2 2025 compared to FedNow at $257 billion.

Theoretically, any user of the RPT or FedNow services could make multiple payments timed sequentially that could add up to larger sums, regardless of the impracticality of having to set up, say, a hundred $10 million payments to pay out $1 billion. The only businesses that need to make an instant payment larger than $10 million in a single payment and then might want a stablecoin choice added to their payment menu would need to be large middle market and large corporates. These are the types of companies that might theoretically want to make an eleven-digit or larger payment. But businesses in this camp are tied to their bankers with more than just a payment choice. Concierge banking counts for something, and let’s not forget the coffee served in the branches.

So what is the worry with stablecoins? How can they be anything other than a more efficient way to make a payment? How can they, with total outstandings equal to $2.5 trillion, really pose a threat to disintermediate banks and take their deposits away, especially since the U.S. commercial banks, with $18 trillion of deposits this month, have $5 trillion more than they need to fund the balance of their loans?

Even with reassurances that stablecoin owners cannot earn interest (at least directly), that they cannot get FDIC insurance, that only authorized issuers can issue stablecoins, and that those approved will need a bank charter, bank treasurers are still worried. That is because their worries are about more than just stablecoins. Bank treasurers are afraid of the entire trend towards instant payments. Instant payments are changing the dynamics around bank treasury, not all for the best, from the perspective of bank treasurers.

Float Away Instantly

Instant payments eliminate delays in moving funds from party A to party B. Bank treasurers like delays because they create float, which makes them money. Lagging is their middle name, from holding back Fed rate hikes to taking their time to clear payments and credit accounts. Almost everyone makes money from float, from the payer to the payer’s bank, and even to the payee’s bank—all parties to a transaction profit from payment delays. You could say they make out like bandits. All, except for the party getting paid late. For them, time truly is money.

Instant payments are frictionless, and friction is the name of the game with float. Instant payments will kill float. Checks create most of the float, given that it can take forever to take a cash check, but credit cards and any other payment system create their versions of float, too.

Float is the phantom money created by delays in the payment process when the debit to the payer’s deposit account is at a different time from the credit to the payee’s account. It is a form of double-counting, an inefficiency in the financial system that creates problems and opportunities. Suppose the credit to the payee’s account precedes the debit to the payer’s account. In that case, there is positive float in the system because both the payer and payee have use of the same funds at the same time until the bank finally debits the payer’s account for the payment. Both can continue to earn interest on their funds until the process completes.

That process takes time, from seconds to days, depending on a list of factors. Many payments are automated and take no time, but large payments, for example, might need some manual processing, too, which adds to the time. There could be mistakes in the payment instructions, a missing date, or a signature on a check. Some banks operate the latest processing systems; others operate last year’s model and might move a little slower.

Thus, if the payer’s bank’s processing system was faster than the payee’s bank’s system, the debit to the payer’s account could precede the credit to the payee’s account. Then, when the Fed debits the payer’s bank’s reserve account for the payment before it credits the payee’s bank’s reserve account, that creates negative float. That is what is happening today.

Most people do not pay their bills by check anymore, but the phrase “check is in the mail” tells you everything you need to know about why checks are practically synonymous with a delayed payment. Checks must clear to access the funds, meaning the payee’s bank sends them to the payer’s bank for payment. The payer’s bank must first verify that the payer has sufficient funds in the deposit account to make the payment and that the payer permits the bank to make the payment. Only then does the payee get their money.

That sounds straightforward, but it is a process with details, and payments are known to get bogged down in the details, those seen and those unforeseen. Today even the oldest check processors use some form of image capture and electronic transmissions but can you imagine back in the days when banks had to send checks by trains, planes, automobiles, and stagecoach, maybe, how long it would have taken to clear a check when it had to go from payer’s bank to the payee’s bank, each located on a different coast or, or maybe even in other countries?

According to the Atlanta Fed, the public only paid 7% of its bills with a paper check in 2024, down from 19% in 2020, a trend that the post office closures and the pandemic probably had a hand in helping along. But just 30 years ago, more than 70% of noncash bill payments were made by paper checks. The American public wrote out 65 billion checks a year in the mid-90s. And before the Fed, paying banks used to discount checks paid to out-of-area banks coming to claim the funds. They pocketed the discount, making the whole check-clearing process iffy and costly for the payee trying to get paid. To compensate for those costs, the payee often up-charged their customers for the use of a check to make the payment.

Making money from float is less profitable today than it used to be, too, at least in terms of what you can earn in interest. For one thing, banks do not pay much interest on savings. These days, the average rate that a bank would pay the payer for the float if left in aninterest checkingaccount would be no higher than 6-7 basis points. If the funds were in a money market depositaccount, the payer could not expect to earn much more than 60 basis points.

Float Used to Confuse Monetary Policy

Fed float today equals minus $675 million, just a basis point compared to the Fed’s $6.6 trillion total assets. Trending just under $0 since the GFC, it has been a minuscule drag on reserve deposits. But back in 1979, the Fed’s balance sheet equaled less than $100 billion, reserves were less than $20 billion, and float on the Fed’s balance sheet had just surged to $6.7 billion, so it was a much more significant number that Fed watchers watched. Float was relatively big in those days, because the public paid almost all its bills with checks (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Federal Reserve Float

Float was a significantly unstable variable in the Fed’s monetary policy plans, as it managed a scarce reserve policy in those days, unlike today, when its policy assumes that the supply of reserves will remain abundant. The balance of reserve deposits on its balance sheet today continues to hold steady at $3.3 trillion, unchanged since it began quantitative tightening more than three years ago. But in 1979, the Fed float was getting in the way of monetary policy, increasing or decreasing the supply of scarce reserves for purely technical reasons, related to the weather, a computer glitch, or human error.

And so, beginning in 1981, the Fed made a concerted effort to minimize float on its balance sheet, and brought the number down to near $0, where it has held ever since. It forced the system to cut the time it took to clear checks, when it used to take a whole business week sometimes to clear them. Even with the new requirements and technological improvements that the Fed led to modernize the payment system over more than four decades, it probably will never get the float number to equal absolute $0, even if the weather may no longer be the reason for float. Human error can still complicate the process, and while AI innovations could reduce those glitches, some payments are just too complicated to automate.

And try as much as businesses and the Federal Government have done to discourage checks, they will never go away entirely, either. There is always going to be friction with checks, but all payment systems come with delays, even instant ones. ACH is a batch system that employers, for example, use to make their payroll. It is a lot faster than paying someone with a physical check, but it can take 1-3 business days.

Same Day ACH is as fast as the title implies, but there are cut-off times that can slow down a payment. Like a train leaving the station at a scheduled time, if the payer is not on time, they may have to wait for the next one. Wire transfers, which many businesses use to make large payments, can take a few days to clear.

Even instant payments can take time. For example, paying someone with Bitcoin could take 10 minutes on average and as long as an hour to complete a payment, including sending confirmations to the parties. Ten minutes is slow compared to Ethereum, which can take from seconds to a minute or two to complete a payment. Instant Visa takes about 30 minutes to complete a payment. FedNow and RPT take a couple of seconds max to complete a payment.

Technology glitches can be one reason for a delay, and even though the payment is digital, geographical distances between different servers (also known as latency) can slow down payments—the more steps involved, the more time a payment can take to complete. Steps for paying with a stablecoin include converting cash to a digital form, sending it to an exchange, and then converting the digital form back into cash. All these steps create potential bottlenecks. There could be congestion with updating the distributed ledger system when many coin holders are all looking to do something at the same time, or even the size of the transaction can play a role in slowing down a payment, as New York Fed researchers found was sometimes the case with Bitcoin payments.

Instant Payments and Stablecoins Create Liquidity Challenges

Demand by businesses and households for instant payments is growing. There is no stopping the trend. Total instant payments worldwide in 2024 equaled $22 trillion and could top $58 trillion by 2028. Bank treasurers can look at this trend two ways.

On the one hand, instant payments bring significant efficiencies to payments. Paying someone with anything other than physical cash is not free. It costs $4 to process a check. A wire transfer could be five to ten times more, depending on whether the wire is domestic or international. ACH payments are cheaper but still cost a dollar. Credit cards are expensive for merchants accepting them, and they tend to upcharge consumers using them for payments, just like they would if they wanted to pay by check. So, even if they do come with some fees, instant payments will still make paying cheaper than it is today for the payees and payers.

On the other hand, instant payments, stablecoins included, come with their liquidity challenges for bank treasurers, who may find themselves scrambling on a Friday afternoon to prepare for a large weekend payment expected over FedNow. Before instant payments, bank treasurers could delay disbursing funds to wait for an anticipated inflow, but instant payments mean no delays. With instant payments, bank treasurers end up with a larger base of demand deposits and will need to hold more HQLA to absorb cash outflows than they might have done in the past.

According to research by researchers for the National Bureau of Economic Research,

“Depositors benefit from immediate payments, but this convenience inadvertently implies a loss in banks’ autonomy in managing the timing of their payment flows. As our model shows, the reduced capacity to delay and net payments leaves banks more exposed to the volatility of payment shocks, which induces them to hold a larger proportion of liquid asset buffers and a smaller fraction of illiquid assets. That is, banks are effectively becoming “narrower.”

The downside of holding more HQLA is that it makes bankers take more risk with the assets that are not so liquid, as the researchers also found,

“Because of banks’ increased holding of liquid and safe assets, they also become more incentivized to take on credit risk when investing in illiquid assets such as loans.”

Tellingly, even making riskier loans does not necessarily improve earnings. Banks handling instant payments end up making fewer loans than they might have wanted and holding more lower-yielding HQLA than they would have preferred, exposing them to more credit risk, and not much to show in income for the trouble, as the researchers concluded,

“Banks’ increased risk-taking increases loan risk premia but decreases loan income per unit assets because the lower ratio of loans over bank assets dominates.”

Payments with stablecoins do not directly impact bank liquidity or deposits because the funds backing them are managed off-balance sheet and are not in the control of the bank issuer. With other instant payment methods, the impact would be direct. However, anticipating that customers would want to shift deposits into stablecoins could have the same effect on liquidity decisions.

Last year, the European Union adopted bank regulations covering instant payments, effective this coming October, that will require bank treasurers working for institutions operating in its member states to make far-ranging changes to their liquidity management practices and model assumptions. For example, bank treasurers think about daylight and overnight liquidity, but the distinction between business and after-hours hours blurs in an instant payment world.

The regulations will require them to plan for the unanticipated weekend payment with a weekend liquidity buffer, provide intraday reporting, and conduct liquidity stress testing to manage a world with no downtime. They introduced a new metric that bank treasurers will be required to track and report to supervisors, called the “Largest Net Negative Cumulative Position,”which equals the largest negative balance that can occur on a weekend that they will need to forecast based on historical data and using multiple stress scenarios.

What’s Driving the Demand for Instant Payments?

Businesses want instant payment capability because their customers want it, and customers like it for a variety of reasons. The Gen-Z generation wants it the most of any age demographic, a group that prefers using a debit card to a credit card and spending within their means. And many of that age group consider putting in even a four-digit pin a pain point that “they can’t even.” And pain points can mean the difference between sold and not sold in their world. But as far as other demographics are concerned, once customers set it up, they typically and quickly see how instant payments are easy to use and less expensive than other payment systems offered by the businesses that serve them.

According to a Fed business survey conducted this year, nearly four in ten businesses of all sizes want a digital wallet to manage loan disbursements and paydowns. More than a third of those surveyed want instant payments to handle recurring bills and invoices. A growing percentage wants their banks to offer just-in-time, business-to-business (B2B) payments, including same-day ACH. Requests for payment transactions, which are a service provided with RPT, were up eight percentage points to 22% in this year’s survey compared to last year’s.

Instant payment use-cases that the businesses surveyed foresee are unlimited, including large insurance payouts and legal settlements. However, this does not mean that small-value use cases for instant payments do not exist, such as for refunds and rebates. Two-thirds of businesses surveyed said they would use instant payments if their bank offered the service.

Everything is going instant. FedNow sees demand for instant payroll and instant bill pay, as businesses seek out the efficiencies and the opportunities to move large sums in an instant, with no limit, as a survey respondent from a large servicer business explained,

“We need the ability to quickly process transactions, whether it’s through cards, ACH or integrated payments. A smooth and user-friendly system will reduce friction and speed up order fulfillment.”

A large construction business owner said,

“We need to incorporate faster digital payments that encourage clients to do business with us, directly improving sales.”

A medium-sized service business-owner was focused on the benefits instant payments offer for managing liquidity, cash flows, and working capital,

“Faster payments enhance liquidity, especially managing working capital. Implementing automated invoicing and payment tracking systems to streamline financial ops, reduce error and improve cash flow management.”

Even small businesses recognize the important of instant payments. Many see the ability to make instant payments to improve cashflow and reduce costs, as a small service provider said,

“We need to transition from receiving payment by mailed checks to electronic payments with apps, invoicing systems, software, technologies, and banking accounts to handle mobile payment and electronic payments.”

Even a very small business owner saw instant payments as a game changer for profits,

“It is hard to get customers to pay invoicing on time without a digital payment platform. We need to find a platform we can pay bills and receive payments online.”

Cross Border Use Case

Businesses and maybe consumers might be warming to instant payments, but the demand for a stablecoin over all the other instant or near-instant payment systems they already have access to is a much bigger demand, a bigger number than the entire U.S. GDP last year, real or nominal. Because this month’s newsletter big reveal is that, according to the IMF, global cross-border payments in 2024 were nearly $1 quadrillion. And just to crunch out those numbers for a second, one basis point on $1 quadrillion equals $100 billion a year. Given the size of this use case, bank treasurers should look forward to generating lots of interest income as a stablecoin issuer in the coming years.

And the story gets better for bank treasurers in the U.S. because guess what. About 80% of that volume went through a bank, and 53% of those banks were in the U.S., compared to Euro-Area banks with 18% of the cross-border traffic. Chinese banks grew from 1.4% of the payment flows in 2021 to 3.7% in 2024. And most of this cross-border flow is especially suited to stablecoins, because the survey found that 83% of payment flows through banks were for payments over $50 million. The IMF survey found that 60% of the payment sums were larger than that.

Making a cross-border payment is not cheap, even if, according to a Financial Stability report from last year, the cost is coming down some. Both the payer and payee get socked with fees, some hidden and some explicit. First, there is the bid and offer spread for the foreign exchange, where banks build in their profit. Customers also pay a nominal upfront fee to complete the transaction.

Stablecoin Economics

There are opportunities and costs with stablecoins. If one of your depositors pulled cash from their checking account and asked you to issue a stablecoin for the sum, the money in the account will no longer sit on your balance sheet. The deposits would move into the equivalent of a third-party managed sweep account off-balance sheet and collateralized by T-Bills and U.S. dollars. You will not be able to use the deposits to make loans, so that is a downside, but the growing trend to instant payments probably will force you to make fewer loans anyway to make way for more HQLA.

But with the earning assets for the reserve fund held off-balance sheet, your bank will earn 100% of the interest income, just like if they were on your balance sheet. The difference would be that you would not incur a capital charge for the T-Bills held in the third-party managed reserve fund. Even under the newly ended enhanced Supplementary Leverage Ratio that the regulators proposed last month, you could not hope for a better deal. Issuing a stablecoin means you can have your interest rate “cake” and “eat it,” too.

You may not be able to avoid any capital charge. Operational risk with stablecoins will lead bank examiners to demand operational risk capital. Just because the deposits move off the balance sheet does not mean the bank issuer is relieved of its fiduciary responsibilities that could hold it liable for customer losses, as bank regulators wrote in a statement released last month. For that matter, general costs to carry more HQLA will also reduce returns. But whatever those costs, a stablecoin issuer would still make out ahead; the capital and liquidity costs will pale compared to the interest income they will earn on the reserve fund.

And the liquidity dynamics with stablecoins to convert them back into their fiat currency are not as fast as the process of using them to pay for things. Stablecoin issuers must make timely redemption into the stablecoin’s underlying fiat currency. But under the guidelines that the New York State Department of Finance wrote in 2022, for example, timely does not mean instantaneously, as an issuer can take up to 48 hours to complete the redemption and sometimes longer if, say, the issuer was a bank and the coin holder requested to cash it during a three-day holiday weekend.

The chairman and CEO of one of the global banks likened stablecoins to mutual funds, because, with funds, too, redemption does not necessarily mean that the customer can get their money instantaneously. He also wondered whether stablecoins were a solution looking for a problem to solve, because banks like his already meet demand from customers for instant payments. But he did see the value of programmable stablecoins to address concerns for fraud and money laundering,

“I’m not against stablecoin. It’s like a mutual fund. But mutual funds have rules. What are the rules can be around stablecoins?...It’s a little bit of a solution looking for a problem, because if I’m going to send you -- we already have the - Coin. We already move money 24/7… quite effectively, efficiently, safely, with all the cyber protection…There are things that stablecoins maybe can do that traditional cash can’t. Like, it’s programmable. I might be able to send that stablecoin. Then you can send it to 10 different vendors you want to pay on a regular basis.”

Fintech Rush Into Trust Charters

Theoretically, any company can issue a stablecoin under the GENIUS Act, including banks, nonbank financial institutions, hedge funds, and insurance companies. Even industrial companies not engaged in any financial activities can issue them. But the law requires that the Stablecoin Certification Review Committee (SCRC), comprised of the Treasury Secretary, the Fed chair or Vice-chair of Supervision, and the chair of the FDIC, must first approve a nonbank issuer. To issue a stablecoin as a nonbank, the SCRC must unanimously approve and determine that the public company will not pose “a material risk to the safety and soundness of the US banking system, the financial stability of the US, or the federal deposit insurance fund.”

So, if a fintech decided that it would be a great idea to issue a stablecoin, its best bet would be to get chartered like a bank, and the bank charter of choice for fintechs today is the national trust bank charter supervised by the OCC. National trust banks cannot take deposits or make loans, but the OCC does not regulate them as stringently as it does with traditional commercial banks. Community bankers complain that the fiduciary activities the fintechs propose to take on with these trust charters, including managing the reserve fund and other safekeeping responsibilities related to a stablecoin issued by the fintech, are the economic equivalent of making loans and taking deposits. In a letter to the OCC, the Independent Community Bankers Association complained,

“Traditionally, a national trust bank acts as a custodian who provides safekeeping services for the assets of trust beneficiaries. This may include the safekeeping of securities, estate planning services, or long-term wealth preservation. Traditional trust bank departments do not compete with traditional commercial banks because they do not lend or offer deposit accounts to retail customers…As a national trust bank, First National Digital Currency Bank, N.A. (FNDCB) is legally prohibited from taking deposits. However, by managing Circle’s USDC reserves and facilitating the issuance of USDC, FNDCB will enable Circle to offer a product that functions similarly to a demand deposit, and which has the potential to drain deposits out of traditional banks.”

Trust banks may not be able to make loans or take deposits, but they could maintain a master account at the Fed with reserve deposits, giving them the same access into the payment system as any other commercial bank. Over the last year, there were thirteen applications for trust bank charters, only five of which were approved, and all were commercial banks. One of the applicants withdrew its application.

The seven pending applications at the OCC are from fintech firms, which should tell bank treasurers something about the profits they can make in the stablecoin space. The fintechs might be on to something, something big. The number quadrillion comes to mind.

Stablecoins and the Transporter Room

According to some estimates, the diameter of the universe might be 270 sextillion miles, which, for the record, is 1 million times a quadrillion. At the rate money is growing these days, $1 quadrillion in cross-border payments in a year might seem like nothing one day. But you need the right, most up-to-date technology to handle that flow, with the capacity to scale up or down. Speed is of the essence, whether we are talking about crossing the universe or handling gazillions of dollars in payments.

Fans of Star Trek, the old sci-fi television show, remember that Captain Kirk used the Transporter Room to leave the starship to go down to a planet. Standing in the bay area, Scotty, the first engineer, operated the machine that turned Kirk into a shimmering cloud of light photons, which he then sent in a stream down to the planet, where they would rematerialize back into his human form. The whole process took a couple of seconds and almost always worked out fine, going from the transporter room to the planets and back again. But there was that time when a computer glitch caused Kirk to end up in the wrong dimension, and Scotty was very challenged to get him back to the right one.

The great thing about the transporter room was that it worked instantaneously, but the bad thing about it was also that it worked instantaneously. If you are traveling around these summer days on a plane, you know all about delays, and even if you never saw the TV show, you probably fantasized about having such technology during a long flight delay. Travelling by plane, even with the delays, is still a lot faster than driving or walking, of course. But delays are a drag, whether we are talking about travel or payments.

On the other hand, getting somewhere instantly is not always opportune. For example, usually London time is five hours ahead of New York City. If you need to travel between the cities, the flight time is about seven or so hours, depending on which way the winds are blowing during the year over the Atlantic Ocean. The good thing about those seven hours spent on the plane, assuming no delays, is that a disciplined traveler from New York can use them to reduce the effect of jet lag. Traveling in Business or First naturally makes that easier, and you can even enjoy a fine meal and a movie in the process. Transporter room technology could get you there instantly, of course, but that would leave you with no defense against jet lag, and there is no hope for a meal or a movie. Some float time is not bad.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2025, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief

This Month’s Chart Deck

The case for a rate cut next month remains unclear after this month’s inflation data. The real effective Fed funds rate (Slide 1), based on the nominal Fed funds rate less the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) inflation rate, is still above the historical average going back to January 2000, and suggests that the overnight rate is still too restrictive. However, inflation remains an unpredictable variable, and several Fed officials still sound cautious. They may be leaning to delay rate cuts until next year until they can see more evidence that it is getting back to the 2% target range.

Even if the Fed cuts the Fed funds rate in the fall, there is no guarantee that this will help bank treasurers who still contend with deeply underwater bond portfolios, including both bonds in held-to-maturity (HTM) and available-for-sale (AFS). The fair value (FV) of their total portfolio remained at $0.5 trillion below their amortized cost (AC) (Slide 2) at the end of the last quarter, 100% of which were in their mortgage-backed securities (MBS) books (Slide 3). Total unrealized losses for HTM and AFS fell from 25% of Tier 1 capital at the end of 2022 to 20% last quarter (Slide 4), attributable to run-off in Treasurys. Banks also have less exposure to bonds. At the end of 2022, their investment portfolio equaled 24% of total assets, which they reduced to 20% at the end of Q2 2025 (Slide 5).

Despite the underwater bond portfolio’s heavy drag on their interest income, the industry continued to widen net interest margins (NIM) in the last two years (Slide 6), which on average reached 3.7% in Q2 2025 according to data collected by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC). NIMs have not been this wide since the onset of the pandemic, and are up from 3%, a 25-year low, in Q1 2022.

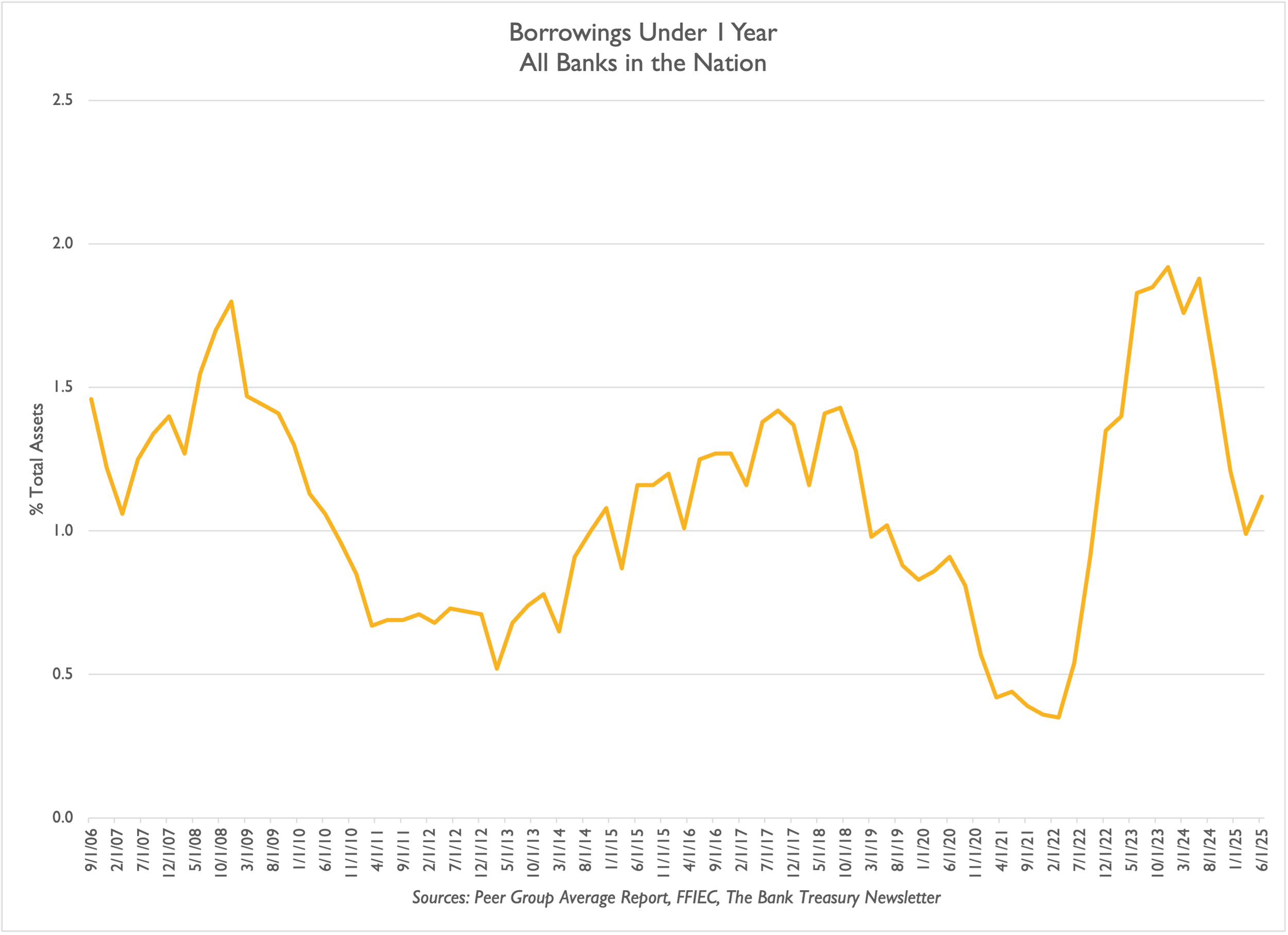

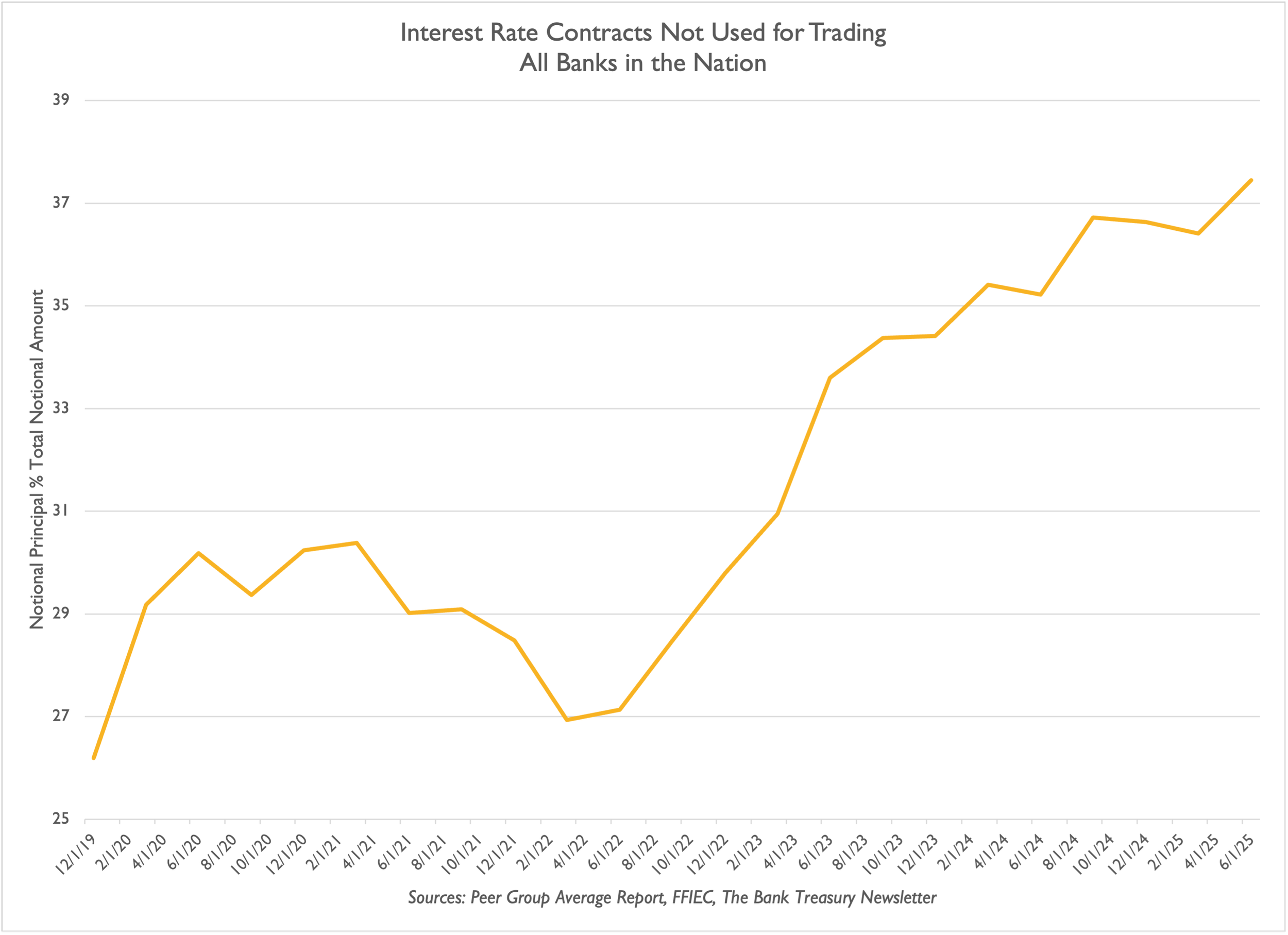

Even as the industry has been repricing its time deposits lower all year, depositors continue to roll and add cash to their accounts. Total assets funded with time deposits maturing in less than one year increased from 12% in 2022 to 22% this last quarter, a 13-year high (Slide 7). Demand deposits as a percent of total deposits, at 25%, is unchanged over the previous four quarters, a remarkable streak compared to its history over the past 25 years (Slide 8) which has been more volatile. As their deposit funding pressures eased in the last year, bank treasurers let some of their short-term borrowings from the Federal Home Loan Banks run off, but that trend seems to have flattened out in Q2 2025 (Slide 9). Finally, bank treasury hedging activity, measured by the notional principal of interest rate swaps not used for hedging (Slide 10), continued to increase last quarter.

Real Rates Head Lower As Inflation Edges Up

No Relief In Sight For Underwater Bond Portfolios

MBS Accounts For All The Pain

Capital Exposure Improving But Still Massive

Asset Mix Continues Tilting Away From Bonds

Net Interest Margin Back To Pre-Pandemic

Depositors Continue Adding Time Deposits

Demand Deposit Trends Flatten

Borrowings May Have Found A Floor

Hedging Activity Up In Q2 2025