BANK TREASURERS NEED BETTER DEPOSIT INSURANCE

The Senate Banking Committee convened on September 10 to hear testimony on potential reforms to deposit insurance, emphasizing the need for change due to the existing system's inadequate service to the public. Back on May 1, 2023, on the day that First Republic failed , the FDIC outlined three approaches that Congress could take with reforms: 1) to increase the insurance cap but still leave depositors with limited coverage, 2) to offer the public unlimited insurance coverage, or 3) to offer the public targeted insurance coverage that depositors can purchase in addition to the FDIC's basic limited deposit insurance coverage.

Deposit insurance emerged as a topic in Congress in 2023 after the FDIC guaranteed both insured and uninsured depositors at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank when they failed. Since then, the issue has languished without a hearing in Congress until now. The cap, which Congress set at $250,000 per deposit account in 2010 as part of the Dodd-Frank Act, is high by international standards. Still, bank executives at mid-sized and community-based regional banks who testified at the hearing explained why some of their business depositors needed a cap as high as $20 million. The topic remains highly controversial in Washington, D.C., where community banks and businesses are lobbying for a higher insurance cap while tax advocacy groups are lobbying against it, because it will end up raising bank fees and eroding service.

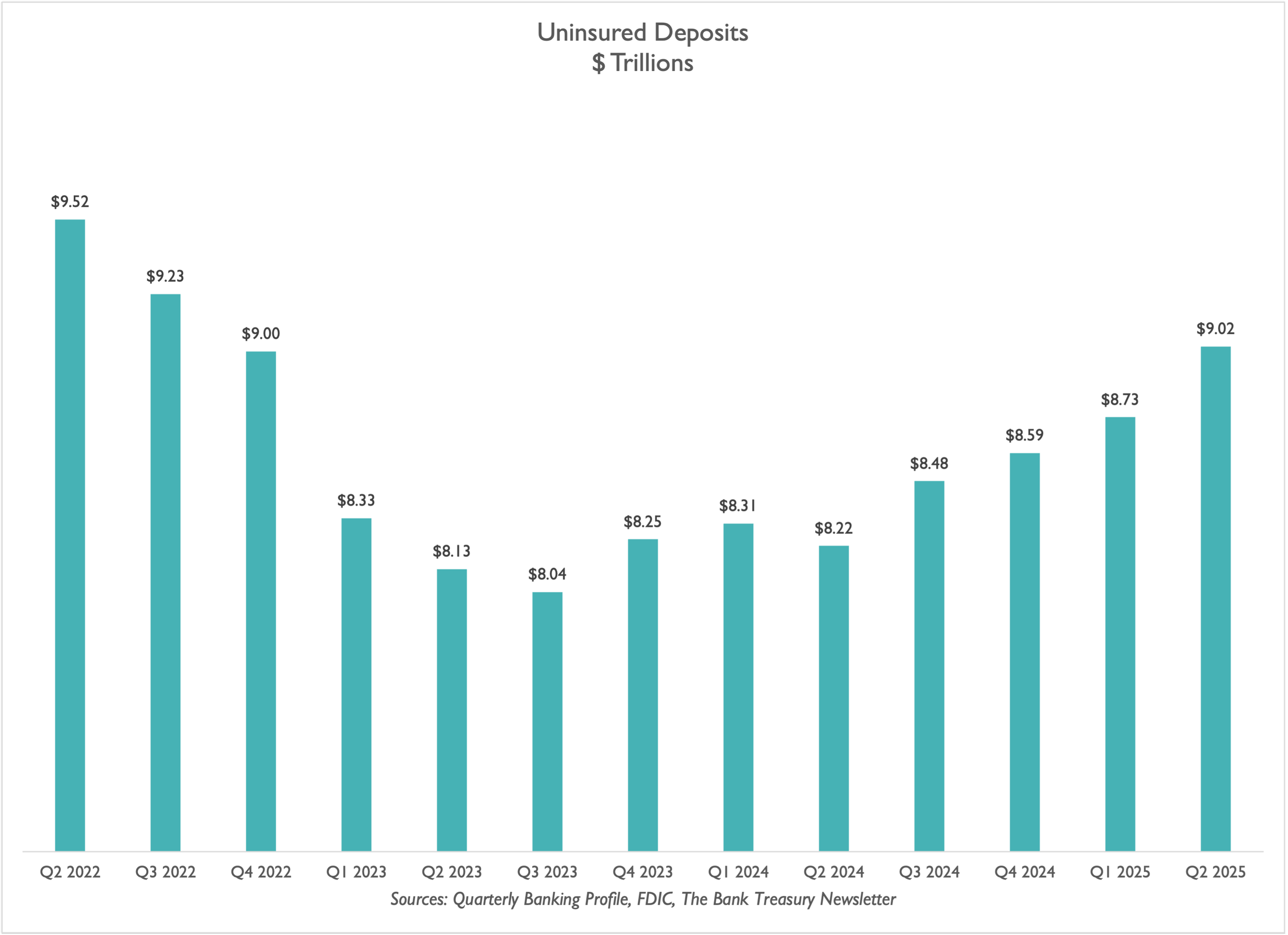

The average uninsured deposit balance according to call reports was $2 million in Q2 2025, and in aggregate, total uninsured deposits equaled $9 trillion, compared to insured deposits, which equaled $11 trillion. But while total domestic deposits grew by 4% in the last year, insured deposit growth is flattening. Indeed, if present trends continue, insured deposits could even shrink.

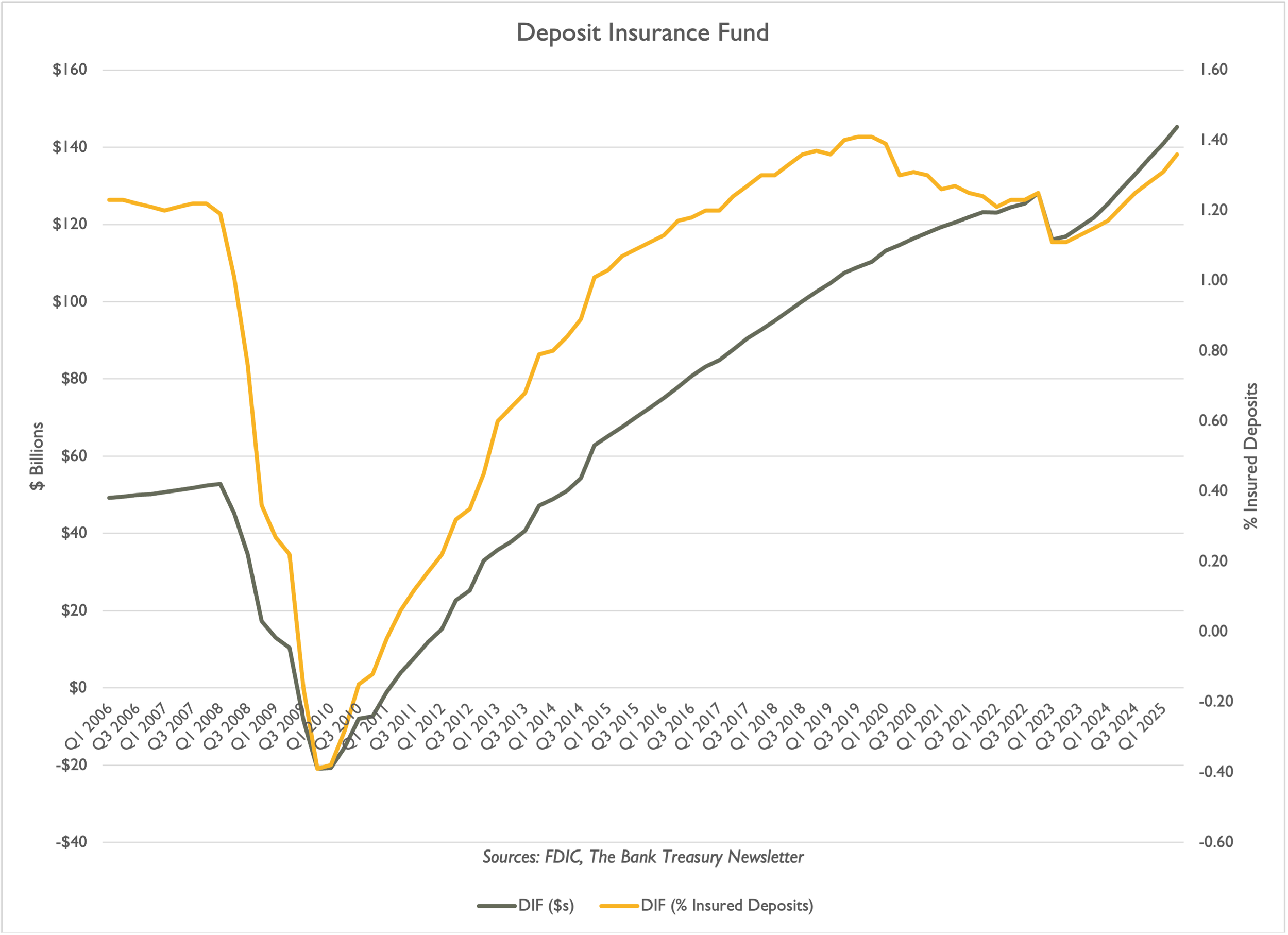

Special assessments, 75% of which the American Bankers Association (ABA) estimates banks with total assets over $50 billion pay, added $13 billion to the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) over the last four quarters, which increased it to $145 billion at the end of last June, or 1.36% of insured deposits. By law, the DIF must exceed 1.35% of insured deposits, which Travis Hill, acting chair of the FDIC, directed staff to examine whether to change the denominator from insured deposits to total liabilities to conform with the calculation for an institution's assessment expense.

The FDIC's Designated Reserve Ratio (DRR) is 2.00%, meaning that the FDIC still has more assessments to collect from the industry before it would be theoretically possible for the FDIC to suspend assessments for most financially strong institutions, a policy it last followed from 1997 to 2007. One of the ABA's recommendations to Congress was to reverse the 2017 tax cut law, which had prevented banks with total assets over $50 billion from deducting their deposit insurance premiums for tax purposes.

The Fed cut the Fed Funds rate by 25 basis points, reducing the range for the effective rate to 4.00%-4.25%. The vote was 11 to 1 in favor of the quarter-point cut, with newly confirmed Fed Governor Stephen Miran, who is on temporary unpaid leave from the Treasury and who assumed former Fed Governor Kugler's remaining term, which expires in January 2026, preferring that the Fed cut 50 basis points. Regardless, the cut was well-telegraphed to the market ahead of the vote, and the overall reaction to the rate cut in the days since the announcement leaves the Treasury yield curve in roughly the same position as it has been for the entire year (2s-10s spread is about 40-50 basis points, and the 3-month-5-year spread is negative 40-50 basis points). The new dot plot suggests that the Fed will cut another 25 basis points before year's end, and the CME FedWatch Monitor rates the odds of another cut for the October 29th meeting at 90%.

Quantitative Tightening (QT) continues. The Fed will let its Treasury portfolio run off at no more than $5 billion a month, and its Agency MBS portfolio run off at no more than $35 billion a month. However, actual run off has been much slower, below the caps set for Treasurys and MBS. Last month, for example, only $1 billion ran off its Treasurys, less than a decimal place considering its portfolio equals $4.2 trillion. Only $14 billion amortized from its Agency MBS book, bringing its balance down to $2.1 trillion. With its reserve account at $3.0 trillion, its lowest level since it began QT in June 2022, and having depleted the balance of its Reverse Repo Facility, which had absorbed much of the runoff from QT cushioning reserves these past two years, the only other account that could offset further runoff from the SOMA portfolio is the Treasury General Account (TGA). The balance in the TGA equaled $0.8 trillion, which the Treasury increased by $0.3 trillion in the last month to prepare for the chance of a government shutdown at the end of this month.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

Deposit insurance reform is back in the news. You must have heard about it. The Senate Banking Committee held a hearing on it this month, and judging by the comments from the committee members, they could not have chosen a better bipartisan topic to take up and do some legislating like they get paid to do.

Addressing the witnesses and his fellow senators from both sides of the aisle, Senator Tim Scott, a Republican senator from South Carolina and committee chair, was clear. Deposit insurance is about as American as apple pie (even if the FDIC is only 92 years old and the first apple pie recipe dates back to 1381 and was invented in England). He was solidly behind deposit insurance, without reservation, declaring that,

“Deposit insurance is central to the trust and confidence Americans place in their banks…That confidence is not just a promise on paper; it’s peace of mind for hardworking families and small businesses. That record of protection is a cornerstone of our economy and the reason deposit insurance is often described as the bedrock of our financial stability.”

Deposit Insurance Is About Peace of Mind

Peace of mind. Deposit insurance is about peace of mind. With the peace of mind that their checking accounts have sufficient funds to cover their bills, people and businesses can go out and grow the economy. Congress established the FDIC in response to the failure of 9,000 banks between 1931 and 1933, which resulted in $7 billion in lost public savings that it entrusted to these institutions, despite their supposed safety. Those were a lot of savings to lose, given that the total deposits in the banking system in 1931 were only $57 billion.

The disaster ruined reputations; bankers held in repute forever after (if the public considered them anything other than scoundrels before). It devastated the public and shook their confidence in the financial system beyond measure. Whatever money the public did not lose in the failed banks, it put back in the mattress, thereby removing needed cash from the banking system. It made the Great Depression a lot worse.

Deposit insurance means the public can sleep at night. Joe Shmoe, who runs a small business, lacks the time and know-how to analyze bank call reports. He has never heard of the Uniform Bank Performance Report or knows what to do with it if he did. The only thing he knows is that when he sees the regulation 7-inch by 3-inch FDIC signage in black lettering against a gold background at the teller window or on his bank’s website, he knows his money is safe.

He knows that his money will be in his account to pay his bills for another day, at least up to the $250,000 covered by insurance. The amended signage rules the FDIC finalized last month will make the regulations simpler for banks to follow, but the message on the signs will remain the same. Joe’s money is safer in a bank deposit account than stuffed in his mattress. That is what deposit insurance is all about—peace of mind.

With Peace of Mind You Get Moral Hazard

But peace of mind has an evil twin named moral hazard. Moral hazard occurs when you let your peace of mind run wild, lose your inhibitions, become overconfident, and take risks you would usually never take. Confidence makes you sloppy. With no worries or hesitations, moral hazard is about ignoring warning signs, like speeding through a crowded intersection right past a stop sign. Because you know that nothing can touch you, and someone else will pick up the pieces of wreckage you leave in your wake through your reckless malfeasance and malpractice.

Moral hazard can be self-fulfilling. It is about Joe’s bank taking needless, even unprofitable risks with his money because heads is a win for the bank’s owners and tails is someone else’s problem. Joe does not have to worry, provided his account does not exceed the insurance cap. Moral hazard is about not looking before you leap or just repeatedly rolling the dice and winning until you lose. You are going to lose if you keep trying; it is just a matter of when and how much.

Everyone hates moral hazard and loves peace of mind, but the two are a package. You cannot have one without the other. Politicians and policymakers have historically hesitated about deposit insurance because it can lead to moral hazard, which can end up costing the taxpayer a pretty penny (that is, if the Government made pennies anymore). But deposit insurance does not just create a moral hazard for Joe’s bank. It creates a moral hazard for Joe, too.

Joe would not need FDIC insurance if he were not so confident that his money was safe. He would read social media more often and not wait to substantiate unsubstantiated claims before acting on his concerns. He would punish his bank for its rumored unsafe and unsound behaviour with his money, line up right away at the teller window, pull out all of his money, and tuck it right back in the mattress where it belongs. Maybe the next time, his bank will think twice before taking a risk with it. Who needs FDIC insurance if you do not trust banks to begin with, FDIC or no FDIC?

But Joe’s sudden deposit withdrawal might lead to a run by other depositors worried like Joe and prone to act on the unsubstantiated story, and cause the bank to fail. In which case, the FDIC could face a bigger loss and a more expensive failure to resolve. This scenario is not far-fetched, as evidenced by bank treasurers who witnessed the fastest wave of bank failures of well-capitalized and highly liquid banks in two and a half years, which occurred unexpectedly and cost the FDIC $22 billion to resolve, covering both insured and uninsured depositors.

Perhaps Joe’s bank should have been more responsive to the social media posts about its health and taken action before it was too late, such as prepositioning collateral at the Fed’s discount window. Ironically, prepositioning collateral might be a good thing for a bank to do for safety and soundness reasons. ButFed researcherscan show that when a bank prepositions collateral at the Fed, it is also more likely to borrow from it. There were 1,996 banks at the end of 2023 (the last reported numbers) that had prepositionedcollateral worth $2.6 trillionat the Fed for that very purpose..

Deposit Insurance and Politics Mix

Perhaps Joe's bank should enhance its risk management, and Joe should refrain from overreacting to rumors. Nevertheless, bank failures are devastating to community stakeholders who rely on the bank for essential financial services, which is why deposit insurance is a public policy priority. And this is why the Senate Banking Committee rightfully convened to hear testimony this month from bank and credit union executives, along with representatives from the ABA, on how to make deposit insurance great again, or at least function as well as Congress intended when it created it 92 years ago.

Deposit insurance is about trade-offs between peace of mind and moral hazard. Trade-offs always involve politics, because politics is the language of getting two opposed sides to cooperate to get anything done. Thus, deposit insurance is all about politics. With politics in the mix, moral hazard and peace of mind can coexist, to the benefit of all concerned — a win-win-win.

There are sides. You have the banks that are in business to maximize shareholder value, just like every other God-fearing business in America tries to do. Deposit insurance is not a moral thing for them. They love it, but not for its social good. Banks view deposit insurance as an excellent way for them to attract low-cost, stable funding to use to make profitable investments on the other side of their balance sheets. Otherwise, what do they care what happens to their depositors' money? It is not like it is theirs!

Then you have the depositors. They do not really care how much money their bank makes or the risks it takes to make those profits (unless they also happen to be shareholders). They just want to know that their money is safe and available to pay their bills on time.

Both banks and depositors agree on one thing. They agree that deposit insurance is excellent, provided the other side pays for it, which is why the Government is yet another side in the conversation. And the novel compromise between all three sides, which created deposit insurance back in 1933, was that the banks would pay premiums to develop and support a deposit insurance fund that the Government would run and backstop when needed. For most of its 92 years, the deposit insurance fund managed by the FDIC has done its job, only supported by the assessments it charges banks based on their total liabilities.

Banks would have a way to offer low-cost deposits to the public, the public would get to sleep at night, and taxpayers would never have to pay a penny because the FDIC would supervise banks against their moral hazard inclinations. The deposit fund would always be sufficient to cover losses. At least that was the thinking. The FDIC was a win-win-win. Which it has been. Public confidence in the safety of bank deposits has been demonstrably critical to the banking system's funding stability and, by extension, the economy's financial health and well-being.

DIFS, DRRs, and Assessments Rates in Basis Points

And for all the griping about the cost of their deposit insurance assessment premiums, it is hard to see the point. Deposit insurance cost the industry $3.3 billion a quarter in the last two years since the regional bank failures in 2023, and it would be a third less of that if it were not for the special assessments the large banks have been paying ever since. But as an expense, the premiums are still a bargain compared to what the industry makes from low-cost insured deposits.

It has been able to use its $11 trillion of insured deposits to fund most of its $13 trillion loan book, for example, which went a long way towards helping it generate the $180 billion a quarter from net interest income it reported last quarter, according to the FDIC’s quarterly analysis. Those deposits remain the source of the industry’s cheapest and most stable funding. Regardless of the advertised teaser rates, the national average rate paid on a 3-month and 1-year CD under $100,000 this quarter was 1.7% while the book yield it earned on its loan book in Q2 2025 was 6.5%.

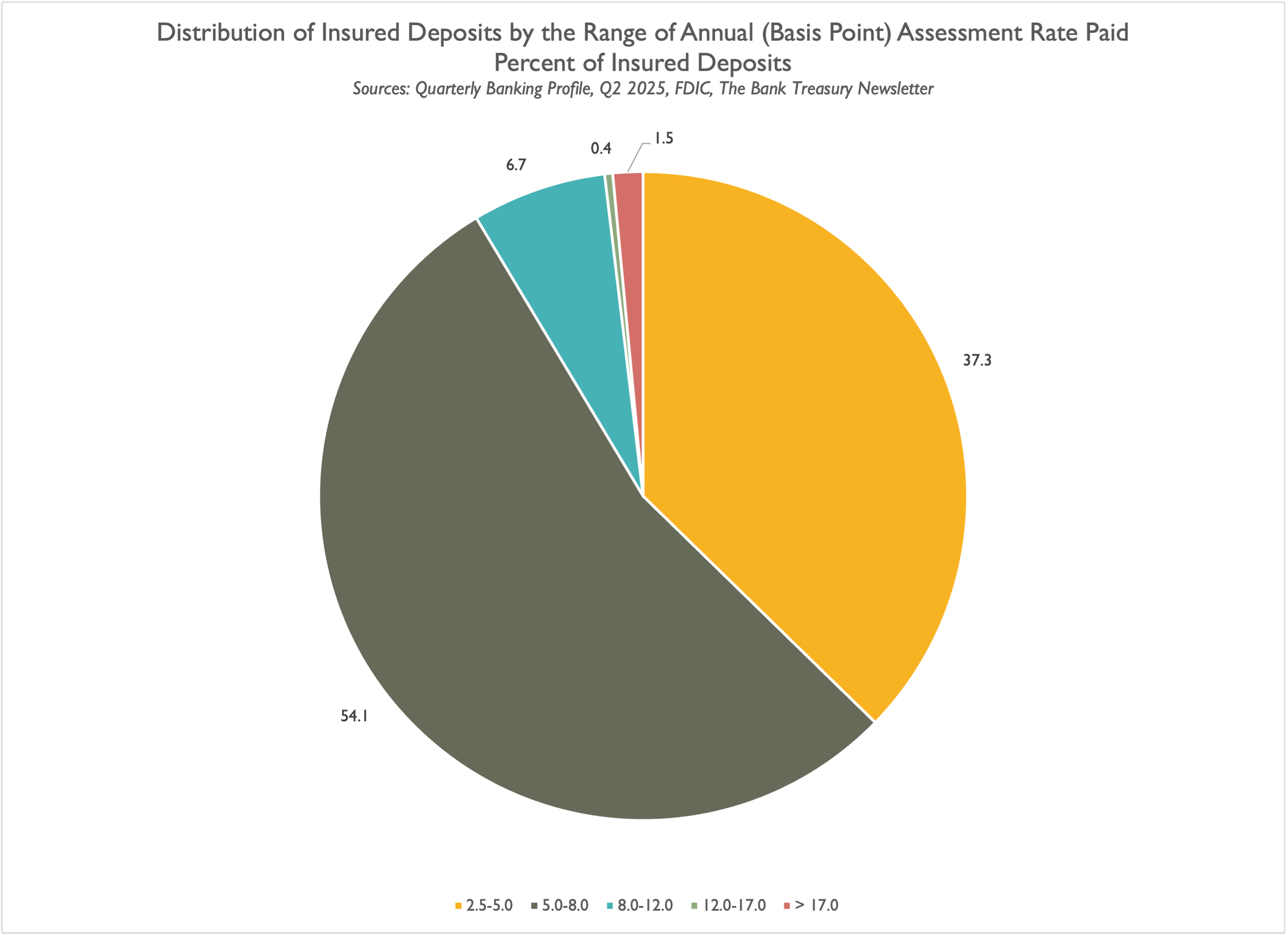

The absolute cost for deposit insurance is mere basis points compared to the value of the deposits the FDIC insures; its assessment rate it charges ranges from 2.5 to 42 basis points, based on each insured depository’s risk profile. Even the special assessment the FDIC began charging the industry to rebuild the DIF after Silicon Valley Bank, Signature, and First Republic failed, and to recover the losses to the DIF, is calibrated in mere basis points, 3.36 basis points assessed against the balance of an institution’s uninsured deposits over $5 billion, to be precise.

The banking industry calculates the dollar value of the assessment by multiplying the assessment rate times its assessment base, which equals its total liabilities, including insured and uninsured deposits, as well as other borrowed funds, both secured and unsecured. However, by law, just to keep it confusing, the DIF, which equaled $145 billion at mid-year 2025, must equal at least 1.35% of insured deposits. It actually equaled 1.36% at the end of June. Travis Hill, the acting FDIC chair, thinks the FDIC should measure the DIF adequacy based on the industry’s total liabilities instead of insured deposits, and directed staff to look into the question.

But either way, the numbers are the numbers--insured deposits equaled $11 trillion last quarter, compared to total liabilities which equaled $22 trillion, so if the denominator changes, so will the ratios. The FDIC also sets a target ratio for the DIF to achieve, called the DRR, which it set at 2% of insured deposits; thus, the FDIC would need to revise it, as well. But regardless, the FDIC intends to grow the DIF through regular assessments for the foreseeable future, even after it ends its special assessments by 2028.

A Record DIF Balance

A 1.36% DIF ratio is a significant milestone, but the record DIF ratio was 1.41% in Q4 2019, which is still well below the 2.00% DRR. But on an absolute basis, with a balance of $145 billion, the DIF is well above any previous level. But why does the FDIC need an even bigger DIF?

With $11 trillion of insured deposits, the FDIC would need a $220 billion DIF, and that is assuming insured deposits do not grow. Despite uninsured depositors after the bank failures in 2023 doing more to distribute deposits and take advantage of ways to get insurance through reciprocal deposits, insured deposit growth has been trending lower since 2023 and was even slightly negative in the first half of 2025 (Figure 1). Uninsured deposits, on the other hand, have risen significantly over the last year (please see this month’s chart deck, Slides 4 and 5).

Figure 1. Insured Deposits

Why does the public need a larger DIF to feel protected, ensuring it will not need to supplement the fund to bail out bank depositors, and that the fund remains sufficient to resolve losses? There were 569 bank failures since 2001, most of which occurred during the GFC wave, accounting for $786 billion in total deposits. The FDIC resolved all of them with the available DIFbalance. And today, conditions for banks could not be better.

Nothing But Blue Skies Ahead

The president and CEO of a mid-sized regional bank in the northeast told attendees at an analyst conference this month that his bank’s customers are optimistic for the year ahead,

“Our clients have been quite resilient…I think that a lot of our businesses…there's less fear, more optimism and people are being cautiously optimistic. And so you're seeing that translate into more loan growth in the industry. We're certainly seeing that at Webster and a continued build of the pipelines.”

A division head for the consumer division of a larger regional bank in the Midwest reported that consumer credit is nothing to worry about,

“We still see credit quality as being quite strong. The consumer is still quite strong.”

Things are going reasonably well and businesses are taking the tariffs in stride, according to the chairman, president, and CEO of a large regional bank in the southeast.

“I think people have gotten more confident with the tariffs and…generally speaking, the economy is doing reasonably well.”

Corporate America has figured out how to handle the tariffs, the chairman and CEO of a large regional bank based on the east coast told analysts,

“By and large, our clients in corporate America have kind of figured out how to deal with this.”

Stable was the word president and CEO of a regional bank based in the upper Midwest described the credit story at his bank,

“Credit has been pretty solid, pretty stable for us.”

The chairman and CEO of a regional bank based in the lower Midwest detected a lot of optimism from his client surveys,

“Do you know, we just conducted our annual survey of commercial clients, and I think despite all the noise around tariffs there was just an awful lot of optimism out there and our clients are really finding ways to deal with it. Whether it's through price increases or changing supply chains or just thinking about the business, they're accustomed to dealing with and overcoming these obstacles, and I feel like a vast majority of our clients are feeling more optimistic this year over last.”

Commercial asset quality and consumer asset quality are just so good, exclaimed the CFO from one of the top four global banks,

“It's been interesting to me just how good commercial asset quality has been, and it's been gratifying to see the consumer.”

And there is a good reason why the consumer is so strong, and not just because unemployment is low. Home values have gone through the roof while mortgage indebtedness is unchanged (Figure 2). The situation for households today differs significantly from before the GFC, when people used their homes as cash registers, unlocking their equity through home equity loans. Household balance sheets today are strong.

Figure 2. Home Values Versus Mortgage-Indebtedness

As he continued,

“So, the question was how you reconcile weak unemployment numbers over the course of the past 3 or 4 months with pretty good consumer asset quality to this point, yeah…So, we haven't seen that yet in our numbers. And I feel like this is one of those consistent things over the course of the past 2 or 3 years where people regularly ask us, have you seen the…consumer weaken? Have you seen the consumer weaken? No, we haven't seen the consumer weaken yet. But there's a lot more than just unemployment. Unemployment is a very important driver for card, no question, number one, but remember also, home prices in a very good place right now.”

Businesses and consumers are strong, having been battle-tested by COVID and other stresses over the past five years, according to the chairman and CEO of a large regional bank based in the northeast,

“I'd say on the corporate side, our clients are in very good position. So one thing that companies got good at over the last, call it, five years has been to become adaptable and resilient. And so getting through COVID, the high inflation, the tariffs, I think businesses have become good at doing different scenario planning and making sure they have alternative ways to run their business in terms of supply chains and things like that…I think, in general, the consumer has stayed strong. Employment levels are still strong, so we're not all that worried all the credit trends in the consumer portfolios are very positive for us.”

Everything is solid, and even office is not looking as grim as it used to look, according to a senior executive at one of the global banks,

“There's no real concentrated area that we're worried about…The one area that we continue to watch is office…And even while office fundamentals are weak, they're starting to see some signs of improvement. It certainly feels like we're off the bottom in office.”

Stable to improving, and no concerns was the way the CFO from a large regional bank based in the Midwest saw his bank’s loan book,

“There are really no areas. It's stable. It's improving…there's not a lot of areas that give us any concern at this point.”

Sentiment is positive, according to the CFO of a large regional bank based in the southeast,

“Sentiment is good. I think there's…a lot of speculation about whether we're seeing the full impact of tariffs. But by and large, on Main Street, it seems that business owners and consumers have confidence to make investment decisions and to expand.”

One reason credit might be so good with banks is that private equity firms are taking on some of the banking industry’s riskiest clients. Banks lend to private investment firms, which then on-lend to these risky borrowers, meaning that banks are not entirely protected. The chairman and CEO of a regional bank based in the West believed that the threat to banks might be a spillover effect if the private equity firms get into more trouble than they expected and start to pull back from the market. When things go wrong, as he said, they go wrong and spectacularly so very fast,

“I think it's been a long time since we've had a real storm…At some point, when something really starts -- it breaks in a big way, I do worry about the lack of a liquidity backstop. I mean they've got lockup periods and everything else that will help. But at some point, those chickens come home to roost. People will want their money out. And if it happens at the wrong time, I worry about the spillover effects into banking.”

Why Pause Assessments Now While Things Are Going Good?

But as conditions stand now, the FDIC’s resolution costs are low and stable. Through most of the previous decade leading up to the bank failures in 2023, the FDIC had been regularly booking negative provision expense against actual resolution losses because it had overestimated the losses it initially expected to sustain. Which makes sense, as well-supervised institutions with strong capital ratios, if they fail, generally do not cost the FDIC much to resolve. So, why again does the FDIC need a larger DIF? Why does it even still need to charge insurance premiums, or should it even consider cutting them?

The last time the DIF exceeded its statutory requirement was following a period when bank failures were low, in the mid-1990s. Congress passed a law that prohibited the FDIC from charging premiums to healthy institutions. There were even times, in the 1950s, and again in 2005, when Congress authorized the FDIC to pay the industry rebates for its past assessments because the DIF’s balance had grown beyond what Congress believed was in the best interest of the banking industry and its ability to generate profits. However, authorizing reimbursements to banks for past insurance assessments was not on the agenda for Senators of the Banking Committee this month, who consider various aspects of deposit insurance reform that all require a larger DIF.

A Tale of Two Depositors

Deposit insurance is a win-win-win situation, but the problem is that the benefits are not always evenly distributed among all parties involved, and sometimes some depositors lose while others win. Not all resolutions are equal for the depositors. True, most of the time, the FDIC arranges for a purchase and assumption, where it picks a healthy bank to buy the failed bank’s assets and assume all of its deposits, insured and not insured.

But not always, especially when banks and their depositors are small. Since the regional crisis in 2023, six small banks have failed. In the disposition of two of these banks, the purchaser did not assume the failed bank’s uninsured deposits. One of them was a bank in Texas with $64 million in total assets, where depositors held $3 million in uninsured deposits, and the other was a bank in Oklahoma with $107 million in total assets and $7 million of uninsured deposits.

Rain does not fall too much where these banks are from, and communities are hardscrabble and overlooked. So it was for these two banks and their treatment by the FDIC, where uninsured depositors were left high and dry. The best hope for uninsured depositors at these banks is that they see a fraction of their savings returned. According to the FDIC, the best-case scenario for the Oklahoma bank is that uninsured depositors will incur a 50% loss. Senator Elizabeth Warren, a Democrat from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, highlighted the disparity in how the FDIC handled large depositors at the three failed banks in 2023 compared to small depositors in the two cases from the last year,

“Take a look at what happened in March of 2023. Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank blew up…To protect from additional bank runs and stop a full-blown financial crisis, the Fed, FDIC, and Treasury took the extraordinary step of guaranteeing all—all—uninsured deposits at those banks. The government backstopped literally billions of dollars in deposits for massive corporations, like the venture capital firm Sequoia, crypto company Circle, and electronics company Roku. And those companies did not lose a penny.”

That was one side, she noted, but then there was another side, the little guy,

“Compare that with two small bank failures in Oklahoma and Texas in the years after SVB crashed and the story turns out to be very different. Local small businesses, like pharmacies and grocery stores and construction companies that kept cash at those community banks, got $250,000 in FDIC coverage and collectively lost millions of dollars on the uninsured balance.”

Deposit insurance is vital for the little guy if he is to have access to the financial system, because he cannot analyze the safety and soundness of the bank where he keeps his money. As she went on to say,

“I don’t think we want or expect small businesses to comb through community bank call reports every quarter to see if it’s safe to keep your transaction account there. I don’t think they should be required to make an investigation to see if there might be executive fraud at the bank when deciding where to have a checking account. The last thing a small-town dentist or landscaping company or a bakery should have to worry about is losing money because their local bank failed.”

Deposit insurance alters the banking industry’s competitive landscape. It levels the playing field between the large banks, which took in uninsured deposits after the bank failures in 2023, and the small banks, which lost the confidence of their uninsured depositors and never regained their deposits. Deposit insurance helps offset the reality that there are banks that are too big to fail, and that the small banks pay for it in higher funding costs. Independent Community Bankers of America (ICBA) President and CEO Rebeca Romero Rainey acknowledged that large banks may require a bailout. Still, Congress could fix that by raising deposit insurance to level the playing field, as the senators heard at the hearing,

“With the federal government using its systemic risk exception to protect uninsured deposits at failed large banks, Congress must ensure that any reforms to FDIC deposit insurance help address the nation’s ongoing problem of too-big-to-fail financial institutions…ICBA looks forward to continuing to work with policymakers to ensure the nation’s deposit insurance system offers community bank customers the same protections as those provided to customers of larger institutions.”

The CEO of a federal credit union echoed her concerns,

“While credit unions remained safe during the March 2023 crisis, we are deeply concerned about the risks posed by implicit guarantees for ‘too-big-to-fail’ banks and the threat this creates for Main Street and our national security.”

There are many sides when it comes to weighing whether and how Congress should improve deposit insurance and address the public’s economic future. There are big banks and little banks, strong, healthy banks, and weak, risky banks with regulatory ratings below satisfactory, big depositors and little depositors, individuals and businesses, taxpayers, regulators, and a lot of other vested interests in the communities they serve. They each have unique needs that merit a targeted approach to deposit insurance reform.

But their needs all start with a higher cap on insured deposits than the $250,000 per account they have now. Sure, there are workarounds, reciprocal deposits, and deposit networks that give large depositors more insurance coverage, but those options are not enough. Moreover, it is insufficient for Congress to decide to punt on reform and merely increase the cap on insurance to reflect the real value of a $250,000 limit set in 2010.

How to Make Deposit Insurance Great Again

Cumulative inflation since 2010 to date equals 48%, which means that Congress should raise the cap from $250,000 to at least $370,000. But that might not be enough. Based on the last call reports, there were nearly 7 million bank accounts in the U.S. (excluding retirement accounts) with balances over $250,000, and the average uninsured account had a balance of almost $2 million.

The ABA outlined 10 recommendations its members would like Congress to incorporate in deposit insurance reform, and raising the insurance cap was just one of them, and not even first on its list. The first recommendation on its list was for Congress to grant the FDIC emergency powers to guarantee all liabilities as needed in stress scenarios at its discretion. The next time there is a Silicon Valley Bank, there should be no guessing and waiting on Congress to vote in an emergency that leads to more uncertainty. That was precisely what happened in September 2008, when House Republicans rejected the initial version of a bank bailout bill widely considered urgent, which led markets to sell off and intensify the financial crisis.

No one-size insurance cap fits all. During the hearing, witnesses from the ABA told the senators that even small community banks have business depositors where $20 million of insurance coverage would go a long way towards helping them help the communities they serve. As the chairman, president, and CEO of a regional bank representing the ABA confirmed,

“We think that $20 million number covers the vast majority of our operating accounts, so we’re very comfortable with that as a group, as our 100 banks in the mid-sized banks. So that’s the number we’re comfortable with, but $250,000 just does not seem to be enough.”

In the same vein, Senator Angela Alsobrooks, Democrat from Maryland, wants deposit insurance to cover payroll accounts, which would be a vital financial service for small businesses,

“Permanently extending deposit insurance to payroll accounts will protect small businesses, community banks, and the people they serve. I am proud to partner with Senator Hagerty in this commonsense bipartisan effort to build an economy Marylanders, small business owners, and all Americans can trust…I want small businesses in Maryland and across the country to have security in the event of another Silicon Valley Bank crash. All small businesses that bank with smaller banks deserve the security larger businesses that bank at big banks receive.”

Deposit insurance reform needs to be targeted, Bill Haggerty, Republican Senator from Tennessee insisted at the hearing,

“Targeted deposit insurance reform is vital to strengthening the regional banks, community banks, and Main Street depositors who support local economies in Tennessee and across the nation,”

If Congress wants to make deposit insurance great again, one place it might start is to make deposit assessments tax-deductible again. In 2017, when Republicans controlled both the House and the Senate, they passed the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).” And wouldn’t you know it, one way they came up with to pay for the tax cuts and the jobs they passed was to restrict banks with total assets over $10 billion from deducting their deposit insurance assessments from their taxable net revenues.

Since then, banks with total assets between $10 billion and $50 billion can only claim a partial deduction for their insurance payments. In comparison, banks with total assets over $50 billion can no longer claim any deduction. According to the ABA, banks with total assets between $10 billion and $50 billion paid for 10% of the $13 billion assessments the FDIC collected in 2024, while banks with total assets over $50 billion paid 75% of total assessments. Tax penalty relief would help banks make more loans, offer higher deposit rates, or just earn more for shareholders.

What is the issue with that? As the chairman and CEO of a bank based in the West said,

“A regulator once explained to me the difference between safety and soundness. He said, soundness is, you've got to make money. He said…we need to make sure that we don't hug this industry so tight that you can't operate.”

And the banking industry wholeheartedly supports good regulation, which will not only help protect the DIF but also help keep it out of trouble. As the CFO from a regional bank based on the West Coast analogized,

“The regulators are a bit like parents, right? They remind you that you should be putting your coat on because it's getting cold out when you go outside. And when you're a child, that seems a bit annoying. And as you grow up, you come to put the coat on yourself.”

Deposit insurance is political, politics are about tradeoffs, and tradeoffs are tough to decide. Raising deposit insurance caps has financial consequences, and some will pay higher assessments than others. As Senator Tim Scott said during the hearing, deposit insurance is excellent, and reform is overdue, but,

“But, as I have learned in the past and said as well, reform is not simple. It comes with trade-offs. Expanding deposit insurance, for example, may provide more security for some small businesses, but if it’s not calibrated properly, it comes at a cost to banks, small businesses, and everyday Americans. The Committee must weigh these trade-offs carefully, with an eye toward what truly strengthens our financial system rather than what simply sounds appealing in the moment.”

There are tradeoffs to deposit insurance reform. He must have already read the letter from the Coalition Opposing the Increase in FDIC Deposit Insurance Limits which said,

“We, the undersigned organizations, representing millions of taxpayers and consumers nationwide, write to express our strong opposition to increasing the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) deposit insurance limit for non-interest-bearing transaction accounts. While framed as a measure to stabilize financial institutions, proposals to increase the limit upwards of $20 million would impose significant and unjustifiable costs on these same companies, with downstream effects borne by American consumers and taxpayers.”

The letter cited facts and figures and complained that the DIF would need to go up and so would premiums,

“According to recent estimates prepared by the Taxpayers Protection Alliance (TPA), raising the deposit insurance cap to $25 million for business accounts (e.g., non-interest-bearing standard commercial checking accounts) would create exorbitant costs. Such a move would necessitate a one-time special assessment of approximately $30.1 billion to recapitalize the DIF to its statutory minimum. Critically, these proposals would increase FDIC premiums by nearly two-thirds (64 percent) over the first five years. The average bank’s FDIC assessment—currently 5.9 basis points—would rise by an additional 4.0 basis points, climbing to 4.3 basis points within five years. Even after the special assessment is satisfied, banks would remain subject to higher annual assessments of at least 1.5 basis points in perpetuity.”

Ultimately, depositors will bear the burden,

“Financial institutions will assuredly pass these costs on to consumers in the form of higher service fees, reduced credit availability, and less favorable terms for small businesses…Moreover, such a drastic expansion of federal insurance coverage fundamentally alters the risk calculus of depositors and financial institutions, embedding greater moral hazard into the system.”

Which is why Senator Scott said that he was definitely and unequivocally, determined to do nothing right away on deposit insurance reform until maybe later,

“That is why I have been clear: deposit insurance reform should not be based on rushed decisions. We are here to build the best policy to protect the American people, promote responsible banking, and maintain confidence and diversity in our financial system – from the smallest community banks to the largest institutions.”

Deposit Insurance Reforms: A Long Time Coming

Rushed is an interesting word for him to use to describe the process. The FDIC first published a discussion memorandum on deposit insurance reform back on May 1, 2023. If FDIC insurance is so bi-partisan, where has Congress been since it came out?

The report outlined three ways for Congress to reform the 92 year old program: 1) Congress can do nothing, or just incrementally adjust the cap on deposit insurance 2) Congress could let the FDIC offer unlimited insurance for all $20 trillion of deposits in the system, or 3) Congress can let the FDIC offer targeted insurance for some depositors and not others. Those are the basic choices which, up until now, Congress has chosen not to make and which Senator Scott is intent on continuing to put off.

The choices are agonizing. More insurance means more bank regulation, which the banks do not want. Expand the insurance umbrella, which everyone wants, but no one wants to pay for a bigger DIF. Alternatively, leaving this problem for the next Congress to decide would be a move that helps no one, but cannot hurt politically.

There are good reasons why Senator Scott might hesitate to do something about deposit insurance reform. It is a thankless effort, at best politically neutral, and not one of those top three reasons a politician can run on for reelection. At worst, the public will blame you for unintended consequences. Deposit insurance reform is not great politics, which is why the last time the subject came up in Congress was 15 years ago with Dodd-Frank, and the time before that was in 1991 when Congress passed the FDIC Improvement Act (FDICIA).

The FDICIA changed the way the FDIC charged assessments, from a flat rate to the risk-based system we have today, incorporating each bank’s supervisory rating to assess the loss the FDIC would incur if it failed. When Congress created the FDIC in 1933, the initial rate the FDIC charged banks for insurance coverage was 8.3 basis points, and Congress fixed the insurance coverage at $5,000. All banks paid the 8.3 basis point nominal rate, and the coverage remained unchanged until 1950, when the deposit insurance fund reached $1 billion and Congress approved the first increase in the coverage from $5,000 to $10,000.

Compared to Congress’s hesitation over the last 35 years to touch deposit insurance legislation, it showed no such reticence from 1950 to 1980. Congress passed legislation to raise the FDIC’s insurance cap five times in those 30 years, raising it from $10,000 in 1950 to $100,000 in 1980. It took another 30 years after that hike before Congress raised the cap on insured deposits from $100,000 to $250,000, by which time the real value of $100,000 had fallen by 60%.

Legislating deposit insurance reform has been a good way to invite your political rivals to snicker from the sidelines. Richard Carnell, Assistant Secretary for Financial Institutions in the Treasury Department in 1996, told conference participants, discussing FDICIA hosted by the Brookings Institution, how the law was an embarrassment to everyone connected to it when it passed in 1991,

“The initial response to the FDIC Improvement Act of 1991 was chilly, to say the least. Treasury Secretary Brady called FDICIA a pale shadow of the fundamental reforms…that the nation's banking system so badly needs. The Wall Street Journal reported the widely held view that FDICIA may undermine banks further. President Bush criticized the legislation …and he warned that this shortsighted congressional response to the problems we face increases taxpayer exposure to bank losses. The December 19 enactment date -- three weeks after Congress adjourned -- in part reflected the President's decision to sign the bill privately, with no media event and no champagne. History does not record whether he held his nose.”

No one likes more bank regulation, sometimes not even the Fed governors who vote on it. Asked about FDICIA, Federal Reserve Governor John LaWare said after Congress passed it in 1992,

“How they had the audacity to call it an 'improvement act' I'll never understand.”

And then complained later that summer that FDICIA,

"…piled increasing regulatory burdens on virtually all banking institutions, taking a shotgun approach to past problem areas.”

Congress's goal was to improve deposit insurance by transitioning from a fixed rate to a risk-based assessment rate pricing system. But complaining about deposit insurance reform is a long-standing tradition, even before Congress passed the FDICIA. Right from the beginning, in 1933, the ABA, which supports deposit insurance today, lobbied heavily against it. Francis H. Sisson, then president of the American Bankers Association (ABA), wrote to President Roosevelt to implore him to veto Glass-Steagall, which included legislation that created the FDIC and the insurance fund. As far as he saw it,

"The American Bankers Association fights to the last-ditch deposit guarantee provisions of the Glass-Steagall Bill as unsound, unscientific, unjust and dangerous. Overwhelming opinion of experienced bankers is emphatically opposed to deposit guarantee which compels strong and well-managed banks to pay losses of the weak…The guarantee of bank deposits has been tried in a number of States and resulted invariably in confusion and disaster to the financial structure of the United States…Strong banks should not be assessed to pay a premium for mismanagement."

He knew from his history. No less than 150 bills were introduced between 1886 and 1933 to create a national deposit insurance system that went nowhere. But the ABA president was only half-right about the state funds and their failure rate. The states made two attempts at creating a government-backed deposit insurance fund. The first period was between 1829 and 1866, when six states, led by New York, established funds for bank deposits. The state-run deposit insurance era ended in 1866 after Congress passed the National Banking Act of 1863, which prompted banks to convert from state to national charters. When they closed, the insurance funds sponsored by New York, Ohio, and Iowa had a surplus over their claims.

On the other hand, the funds set up by Vermont and Michigan ended with deficits because the funds did not have enough time after they launched to finish their capitalizations before they were overwhelmed by a wave of regional bank failures in the mid-1850s. A wave of bank failures also doomed a second attempt by states to set up insurance funds between 1908 and 1917, including in Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Texas, Mississippi, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Washington. All of them closed with deficits that state taxpayers had to cover.

For all its flaws, deposit insurance in the U.S. is mostly more generous than its international peers, at least in terms of its coverage amount. Canada, for example, covers deposit accounts only up to $100,000. The U.K. covers £85,000, Australia covers $250,000. Japan has ¥10 million coverage per account, which also equates to about $100,000 USD. In Europe, deposit insurance covers depositors up to €100,000, but depositors can obtain additional temporary insurance for life events such as the sale of a home.

U.S. depositors and their bankers believe that the present deposit system urgently needs reform, and feel frustrated that Congress wants to take its time to do anything about their concerns. But maybe everyone should appreciate that the FDIC’s deposit insurance system might just be the best in the world. Perhaps some of our apple pie recipes popular in the fall originated elsewhere, but our FDIC signage is definitely made here in the USA.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2025, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief

This Month’s Chart Deck

The problem with the FDIC’s deposit insurance coverage system, as bank executives testified this month in front of the Senate Banking Committee, is that it is not working for their bank depositors, especially their business accounts, some of whom say they need $20 million coverage for their payroll deposits. And insufficient coverage complaints by business customers are across the board, large and small. In addition, because of inflation, the $250,000 cap that Congress set in 2010 is worth just about half its value today. However, increasing insurance coverage will result in higher deposit insurance assessments, which large banks, which pay most of the assessments collected by the FDIC, already find expensive, made worse by the fact that they cannot deduct the premium expense for tax purposes. With the balance of the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) already at a record $145 billion, the FDIC is still targeting 2% of insured deposits as a goal it plans to meet through further assessments.

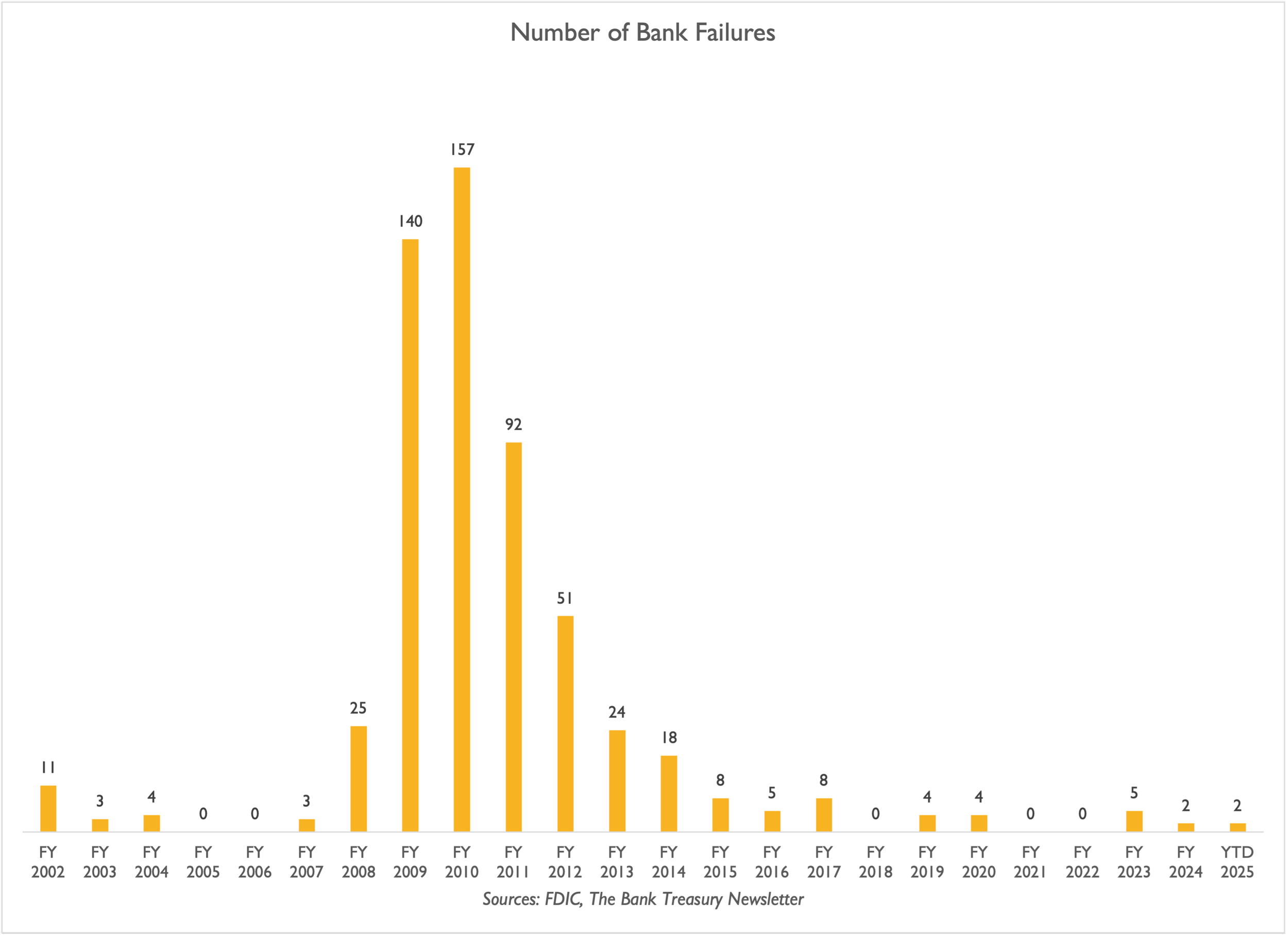

FDIC insurance is a national success story because, for most of its 92-year history, leaving aside the S&L crisis in the early 1980s, the financial crisis in 1989-1991, the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, and the regional bank crisis in 2023, most of the time, thanks to strong bank supervision and capital requirements, the number of bank failures is low and the losses when banks fail have been low, too (Slide 1). As a result, the FDIC can rebuild the DIF after losses deplete it, without needing any additional capital support from taxpayers. Over the last 6 quarters, for example, the FDIC added back to the DIF nearly $1 billion through cumulative negative provisions for insurance losses (Slide 2), which is partly why the DIF now exceeds the statutory 1.35% minimum versus insured deposits (Slide 3).

Meanwhile, depositors seem to be putting more of their savings in uninsured accounts. Thus, the balance of deposit accounts over $250,000 (Slide 4), uninsured deposits (Slide 5), and even the balance of money market funds (Slide 6), which are also uninsured, all increased in the last six quarters.

The low-cost funding that FDIC deposit insurance creates is a critical component of bank treasury and a powerful driver for net interest margins and income. For example, the national rate on a 3-month CD never got higher than 1.6% when the Fed was raising the Fed funds rate in 2022 and 2023, and when the Treasury was paying 3-month T-Bill investors over 5% (Slide 7).

For all its present shortcomings, the U.S. deposit insurance system is still one of the most generous in terms of coverage compared to systems in other countries (Slide 8). And most banks pay less than eight basis points in annual assessments, not only in terms of numbers (Slides 9) but also in size, with the FDIC assessing banks accounting for 92% of all insured deposits in the system between 2.5 and 8 basis points a year against their total liabilities (Slide 10).

Most of the Time, Failures Are Rare

FDIC Insurance Loss Negative Provisions Continue

DIF At Record Levels

Large Depositors Return To Banks

Uninsured Deposits Grow Since SVB’s Failure

Money Market Funds Grow Since SVB

Insured Deposits Are Worth The Deposit Insurance

US Deposit Insurance Cap Versus Other Systems

Most Banks Pay Just BPs For Deposit Insurance

Large Banks Pay Basis Points For Deposit Insurance