BANK TREASURERS TRY TO CONNECT THE DOTS

By most measures, Q3 2025 earnings results presented a bright picture of the banking industry. Performance could certainly be better, and asset quality numbers are not as good as last year's, but they're still within the range of normal. Besides, the industry appears to have substantial capital and is on top of its credit exposures, notwithstanding the embarrassment to banks exposed to the First Brands and Tricolor Auto bankruptcies. Profits were up, net interest margins (NIMs) are ticking higher, and the deposit picture is steady. NIMs continue to benefit from the asset roll-off/roll-on spread, which acts as a tailwind, and from more earnings assets that banks booked when rates were at 0% maturing or repricing.

According to the Fed's H.8 report, domestic bank deposits grew to over $17 trillion last month, which is $100 billion higher than their previous peak in March 2022, and over $1 trillion higher the recent low they fell to in June 2023 in the aftermath of the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank, and First Republic. Loans are also trending higher, reaching a record $12 trillion last month, attesting to the public's healthy demand for credit, even amid uncertainty from tariffs and a government shutdown.

There was more good news on the bank front. Regulators announced their commitment to a much friendlier approach to supervising financial institutions, including pulling back bank examiners from formally citing them for minor infractions with Matters Requiring Attention (MRA), eliminating reputation risk as a category for concern, and limiting reasons for downgrading an institution's composite CAMELS rating (Capital, Asset Quality, Management, Earnings, Liquidity, and Sensitivity) to material financial risks instead of issues solely connected to lapses in governance. Moreover, bankers will be allowed to treat examiner guidance as merely nonbinding suggestions, rather than a new source of extra busy work.

But there is more: the Fed also seems poised to end Quantitative Tightening (QT) very soon. The balance of reserves on the Fed's balance sheet this month fell slightly to $2.9 trillion, the lowest level since the Fed began QT in June 2022, when it stood at $3.2 trillion. While Fed officials still describe reserves as "abundant," they are more mindful than they have been that they are approaching the line between "abundant" and merely "ample." Evidence supporting this view includes greater use of the Standing Repo Facility and firming repo rates for general collateral, rather than Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) and the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR).

According to the CME's FedWatch Monitor, there is a 99% chance that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will cut the target Fed funds rate by 25 basis points this month, to 3.75%-4.00%. Even so, the Fed's dot plot published last month showed a wide range of views among the voting members of the FOMC, from a member who favored no further cuts this year to one who favored rates falling by more than 100 basis points before year's end.

While voting members seem inclined to cut the Fed funds rate, they insist that their votes remain data-dependent, which is a problem: first, during the ongoing Government shutdown, there is limited data, and second, the data they do see is conflicting. Some of the data they say they have seen suggests that employment is either about to be in trouble, or has never been better, while the public's price expectations remain unchanged.

According to Lori Logan, president of the Dallas Fed, who is not currently a voting member of the FOMC but who will be beginning this January, the Fed should be thinking now about replacing the Fed funds rate as a target for monetary policy because the rate no longer derives from a robust enough market to base such a critical benchmark. The Fed has used the Fed funds rate as a target rate for over 30 years. She instead made the case for the Tri-party General Collateral Rate (TGCR).

The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,Kids learn to play connect-the-dot puzzles at an early age. They just need to follow the instructions and hold a number 2 lead pencil, and they can draw a work of fine art that their parents would be proud to scotch-tape to their fridge. Connect-the-dot puzzles help instill in future bank treasurers the value of rule-following in a fun and engaging way. All the while, the puzzles hone their fine motor skills so that one day they will have the sureness and fine hand to draw solid double lines to tally total assets or single lines to net interest expense from interest income.

Would-be proto-Rembrandts do not need to spend years in an art class to perfect their craft, nor do they need to be a natural Bob Ross. All they need to do is to trust the dots, to follow the numbers, to connect the dots labeled “1” to the dots labeled “2,” and in turn draw straight lines from the “2s” to the “3s,” the “3s” to the “4s,” and so on. If they follow the rules, their promised reward —the hidden picture, the meaning behind the dots —will surely slowly emerge from the jumble of dots they first see on the page. And then everything will make sense.

Seeing meaning in the dots and connecting one to the other is an ancient idea, even if the publishing innovation of numbering them is just rounding off at 100 years. Thousands of years ago, the ancients saw celestial beings in the stars above them. They imagined that Sirius, the brightest star at night, was actually the head of a large hunting dog belonging to Orion, a legendary hunter who, after his death, was immortalized in the night sky by Zeus. Following Sirius, the dog star, or the North Star as it is also known, ancient sailors crossed great oceans, and explorers mapped uncharted lands.

Drawing lines was the basis of their temple-building plans for their deities, and so geometry was born. Euclid, 2,300 years ago, based geometry on the premise that there are two points, Point A and Point B, which are distinct. Though neither point has any dimension whatsoever, each is infinitely infinitesimal to the point of being undefined; a straight line extends from A to connect with B to create one dimension. Thus, the AB line segment.

Points are dimensionless, but without them, lines are just open-ended extensions to infinity. Another straight line drawn from B at an angle to the AB line creates a connection to Point C, and a BC line. Lines AB and BC create two dimensions, and x and y coordinates, which bank treasurers care about when they attempt regressions. B is an inflection point, and C becomes another inflection point, creating an x, y, z space, also known as a cube, which follows the 2,500-year-old Pythagorean theorem about perfectly constructed right triangles and hypotenuses.

Which is all fantastic if not for the fact that the world is not perfect, and the stars Euclid saw long ago, which inspired him to think in terms of points and lines moved out of place in relation to one another. They no longer connect in quite the same way to form anything remotely recognizable as they did when the ancients saw Orion and a hunting dog in their night skies. And even if the stars had all been stationary all these years, and none had collapsed on themselves to create black holes, or to supernova, a surface in the real world is not perfectly flat, two lines do not always align perfectly, and in real life, nothing is ever completely straight or on the level. There is always an angle, and the real world has many odd ones.

Connect-the-dot puzzles encourage false expectations about reality. In the real world, there are no hidden pictures in the dots for connecting. Some things will never make sense as a complete picture, at least not to human minds. In the real world, straight lines are hard to draw, and there are no numbered dots. There are no promises or guarantees in the real world, which is subject to chance and rife with uncertainty. There are no dimensionless points or theoretical extensions ad infinitum.

The real world has bumps in the road, mountains, and valleys to go around. The real world is subject to time, and light bends in the presence of gravity. The real world is subject to error and glitches in the model or the data. It has frictions, tailwinds, and headwinds. The real world is round, not flat. Flying around it means traveling along a great circle, not a straight line, and taking roll, pitch, and yaw into account when plotting directions. The real world has outliers and anomalies, it has enduring mysteries, and not everything will make sense one day. And in the real world, not all the dots are visible to connect at the same time; some are subject to change and revisions, and some are dots delayed due to technical issues related to a Government shutdown.

Machine Learning Connections

Navigating the bank treasury world is even challenging than flying around it. Connecting the dots —the data points, the economic statistics, interest rates, balance sheet, and income statement line items — means contending with imprecision, taking into account, and, with a grain of salt, noisy, misleading, and missing data. Straight lines do not get you from Point A to B in the bank treasury world, and neither do circles. You need stochastics, and you need to embrace random walks. Bank treasurers know to account for error. Connecting dots in the bank treasury world is an art form, less a science.

And the picture bank treasurers try to draw is hard to make out from the dots they try to connect. Because it is one thing to say that banking is a cyclical business, and another to explain precisely how. No two banks are impacted by the same scenario the same way. A bad day for the banks that were subject to the regulatory stress tests in 2023, there severely adverse scenario, would have actually been SVB's best day if it had not been exempted that year from taking it. Technology using machine learning and AI can help predict SVB's worst day —the one not on the Fed's stress test.

The software can make the connections that human eyes cannot see. Similar to how doctors use machine learning to detect certain cancers, Straterix software (a corporate sponsor of the newsletter) can identify each financial institution's unique vulnerabilities by projecting its financial statements forward across thousands of potential scenarios and macroeconomic variables. From its reading of the dots, bank treasurers can chart a course through the current landscape, prepared for the adverse developments that inevitably arise along the way.

Because bank treasury is a business based on probabilities, not certainties, it is a world where what might happen this way might not, and scenarios play out in this direction or that. Bank treasurers need to take all those possibilities, and their little details, into account when they draw a picture. Machine learning technologies, which are relatively new in the world of bank treasury decision-making, are a critical tool in asset-liability management, given today's complexities in drawing the picture. As the global bank's chairman, president, and CEO told analysts, AI is not replacing his staff. Instead, it is enhancing what they can do,

“Our view of AI is its enhanced intelligence…critical to delivering the services…it's an enhanced intelligence, not an artificial intelligence.”

Lines between causes and effects, betas and deposit repricing, credit cycles, monetary policy, tariffs, shutdowns, and a whole host of what-ifs separate what a bank’s financial condition is today from where it will be tomorrow. Between point A and B is a vast array of points and lines connecting to other points and more lines, each representing a possible path. Markets go up at Point A, or markets go down, and then, at Point B, the markets go up or stay the same, but at the same time, there is a shutdown or no shutdown. Meanwhile, war breaks out, or inflation rises or falls. Or there is a financial shock at Point C.

Not all dots matter when you try to connect them in the banking world. This time is different really means that this time, one set of factors may be more important than another set was in a previous cycle. Sometimes economic and credit factors threaten a bank’s financial performance. Sometimes it is interest rates and deposit composition that need watching.

Some factors matter more than others. The sell-off in the technology sector four years ago might not have been a proximate cause of Silicon Valley Bank’s failure. But connect the technology market troubles with the Fed suddenly turning very hawkish in 2022, when combined with a crypto-market sell-off, the closure of Silvergate Bank, and the FTX bankruptcy together could be directly linked to its failure, as Straterix founder Alla Gil wrote,

“As a result of the two-shock combination of interest-rate-driven inflation and VC funding withdrawal, the 16th largest U.S. bank collapsed at rocket speed. It would still be alive, however, had it considered the full range of scenarios with all combinations of potential shocks.”

So many factors go into where financial conditions end up that the human mind cannot calculate all of the potential directions in which tomorrow may go. Bank treasurers look at a wide range of possible paths ahead and prepare for them all as best they can, given limited knowledge and confidence in the data. They have to make do with the missing and to-be-determined data, too. Consequently, given that new machine learning technology is out there that could enhance decision-making, finding out about it should be on a bank treasurer’s top priority list.

Nothing to See

From a practical standpoint, given the financial condition of their borrowers, the state of the economy, and what Fed officials have outlined recently, it cannot be easy to generate realistic scenarios that lead to bad days for the banking industry. Of course, it could be better. Bank treasurers all aspire to wider NIMs and greater NII.

But it is hard to see how a bank today could go from what one senior manager at a private financial firm called this month “a perfect environment for banks” — an ideal banking landscape —to a hellscape. Explaining how credit losses turn from normal to crisis level, calm turns to panic in the streets, and where all becomes destitution, markets on their back, and Armageddon is not a one-step process, but multiple steps that take one over the cliff. The path that takes them down a dark alley is complicated. Sometimes, even retracing steps through reverse-scenario analysis and the benefit of hindsight, it is still difficult for them to understand how they screwed up.

Despite all the stresses and strains the economy has already gone through —from pandemic to recovery to raging inflation to geopolitical tensions to market volatility to rising interest rates to falling interest rates to persistent above-target inflation to now a government shutdown, the economy is basically fine. Unemployment is low, and consumers are still spending. The surprise is all on the upside that no one expected.

Even now, no canary stars are forming a celestial picture up above that bank treasurers can identify as an omen. There have been some glitches, a few mistakes, which the First Brands and Tricolor Holdings bankruptcies highlighted this month, that, despite all the lessons learned and experience since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), lenders still make mistakes, some of which will be costly. But as many bank managers told the analyst community this month, everything is fine and there is nothing to worry about. They see nothing.

No, the First Brands and Tricolor bankruptcies are not canaries in the mineshaft, according to bankers seemingly blindsided by the losses. Is credit something to worry about? They do not see a picture in the data points they gather from talking to their customers. As doubts in the financial press fan investor worries over nondepository financial institutions (NDFIs) and Business Development Companies (BDCs), the chairman of the board and CEO of a large regional bank based in the southeast told analysts this month that there was nothing to see,

“I can say, overall, credit quality is strong. Let me sort of start with that as a premise. We have seen in the market I would say today, sort of idiosyncratic and uncorrelated events.”

There is nothing to see or say, according the CFO at a global bank,

“We're not observing anything other than continued strong performance in the credit portfolios.”

Cautious, another global bank CFO told analysts he took comfort in the fact that consumers were still paying their bills on time and spending money,

“I'm still very cautious. We are running our operations in a recession-ready mode. We're watching payments in order to get any early signals of stress. But again, as I look at the book, I feel comfortable with where we are and where our consumers are trending.”

If bank treasurers see a recognizable picture, it is the same one they have seen all year. Nothing changed since the last quarter, the picture is still consistent as far as the consumer is concerned, according to the CFO at another global bank,

“We have very little to say that's different from what we said last quarter, and it's because it's the performance of the consumer is just very consistent.”

So far, every glitch in credit like the First Brands bankruptcy looks to bank management like one-offs, according to the chairman, president, and, CEO of a large regional bank based in the Midwest,

“I suspect there are isolated issues that are in the industry…there'll be some episodic moments and some one-offs, but I think the industry is in a good shape…and many of those who reported are suggesting the consumer is in relatively good shape. We certainly are not seeing forward indicators in terms of delinquency or other measures.”

And as far as lessons learned in hindsight, bankers still struggle to see what they could have done differently, as the president and CEO of a large domestic bank told analysts,

“I don't think we'll do anything differently. We have very, very strong underwriting capabilities. When you have a large book, you have one or two issues. You must be appropriately reserved for it, which we are. You must be diligent…we have a lot of confidence in the quality of the credit book and our underwriting process. So, I'm not sure there's anything to be done differently.”

The CEO of a small regional bank based on the Midwest saw no clouds on his bank’s horizon,

“Right now, things look pretty strong, we're not really seeing…much of a…problem.”

The chairman and CEO of a large domestic bank understood that things can fall apart, but so far, everything looks fine,

“I remain comfortable with the economy as long as there is consumer spend and we don't have a big crack in employment or sign that it's weakening, but thus far, it hasn't fallen. I think the economy is fine.”

In fact, as he continued, he has been surprised by how well the economy has performed given all the challenges,

“The survey that we just did in partnership with Bloomberg with corporate CFOs surprised us to the upside…The vast majority were bullish, not just on our own company, but on the economy, which kind of surprised me. A big part of that theme was the work they've done to work through tariffs, whatever they might be. Just sharpen up their own companies, both in terms of resiliency and just cost efficiencies. The consumer remains strong, deposits are growing. We've got a whole bunch of things that could land on us, but none of them are there and none of them are certain.”

When the economy goes so long without a correction, lenders tend to get sloppy, cut corners, and take risks they should not take. Bank examiners may keep banks in line from slipping, but even unregulated lenders are enjoying excellent credit quality and following the basics of solid underwriting. According to the CFO at a major NDFI, borrower credit quality is stellar,

“I'd say the teams are generally seeing strong credit quality from borrowers. They're generally seeing a positive environment for credit investing. Even in syndicated loan markets, default rates have been declining.”

When the Tide Rolls Out, Dots Appear Naked

One thing about credit cycles, however, is that, as the old saying goes, when the tide goes out, you find out who has been swimming naked. Mistakes come with the territory in banking. But the chairman and CEO of a regional bank based in the West was appalled by the quality of the underwriting involved in the First Brands bankruptcy,

“I was appalled listening to one of the news programs the other day and one of the executives from one of the lenders…was on there, and he said, frankly, we just need to do better underwriting. And I thought, my gosh, you're making loans to complex entities out there. And you just now figured out you need to do better underwriting.”

Good times are forgiving, and bad times are not. Credit issues can emerge later as the credit cycle plays out, confirming another old saying: this time is never different. First Brands might be just a mistake, a blip, an anomaly, and an outlier, but it could be a sign of something much worse, because usually when you see one, you see more. If you see one cockroach, the chairman and CEO of one of the global banks told analysts, there is a good chance you will see more, even if you cannot see how or why, even if you would swear by your underwriting quality,

"When you see one cockroach, there are probably more, and so everyone should be forewarned.”

But you can look as hard as you can for risk and still not see it until the tide goes out and it bites you. That is the problem with risk. It usually is not where you look that you need to worry about; it is where you do not know where to look, and you will only see it when the cycle turns. As the bank executive continued,

“We scour the world looking for things that we should be worried about…Asset prices are high, a lot of credit stuff that you would see out there, you will only see when there's a downturn.”

Connecting Scenarios to NIMs and NIIs

Where will interest rates be next year? Or the year after? How will inflation, which ticked up to 3% last month, get back to the Fed’s 2% target range? Bank treasurers need to answer these questions to project net interest income and net interest margin. Even if they could predict the future with rates and the economy (and still be working for a living), tying economic and interest rate scenarios to outcomes for NIMs and NIIs is complicated. For starters, the standard scenarios they run are unrealistic and useless. As the CFO of a global bank noted regarding his bank’s NIM and NII vulnerabilities in potential rate scenarios such as instantaneous parallel shifts,

“When we talk about asset sensitivity as an instantaneous drop of 100 basis points…that obviously means, number one, that it happens tomorrow. Number two, it exists all year. And number three, it happens at the short end and the long end, all at the same time. So, I don't know how you would assign a probability to that, but it's obviously on the lower end.”

Even when the broad scenario outline is reasonably likely, many smaller variables in the story can shift the effect one way or another for the balance sheet and the income statement. Quantitative tightening also affects deposits and rates, further complicating the forecast. Forecasting deposit growth is tricky this way, as a global bank CFO noted, a lot is uncertain,

“Deposit growth…as we sit here right now and we update the macro environment, a few things are true. One is the personal savings rate is a little bit lower than expected. Consumer spending remained robust while income was a bit lower. So that's all else equal, decreasing balances per account. And as you obviously know, equity market performance has been particularly strong, which is driving flows into investments…that's a little bit of a headwind to balances per account. And relative to the scenario that we had at the time, rates are a little bit higher than what was in the forwards. And that is producing, again, slightly higher than otherwise expected yield-seeking flows.”

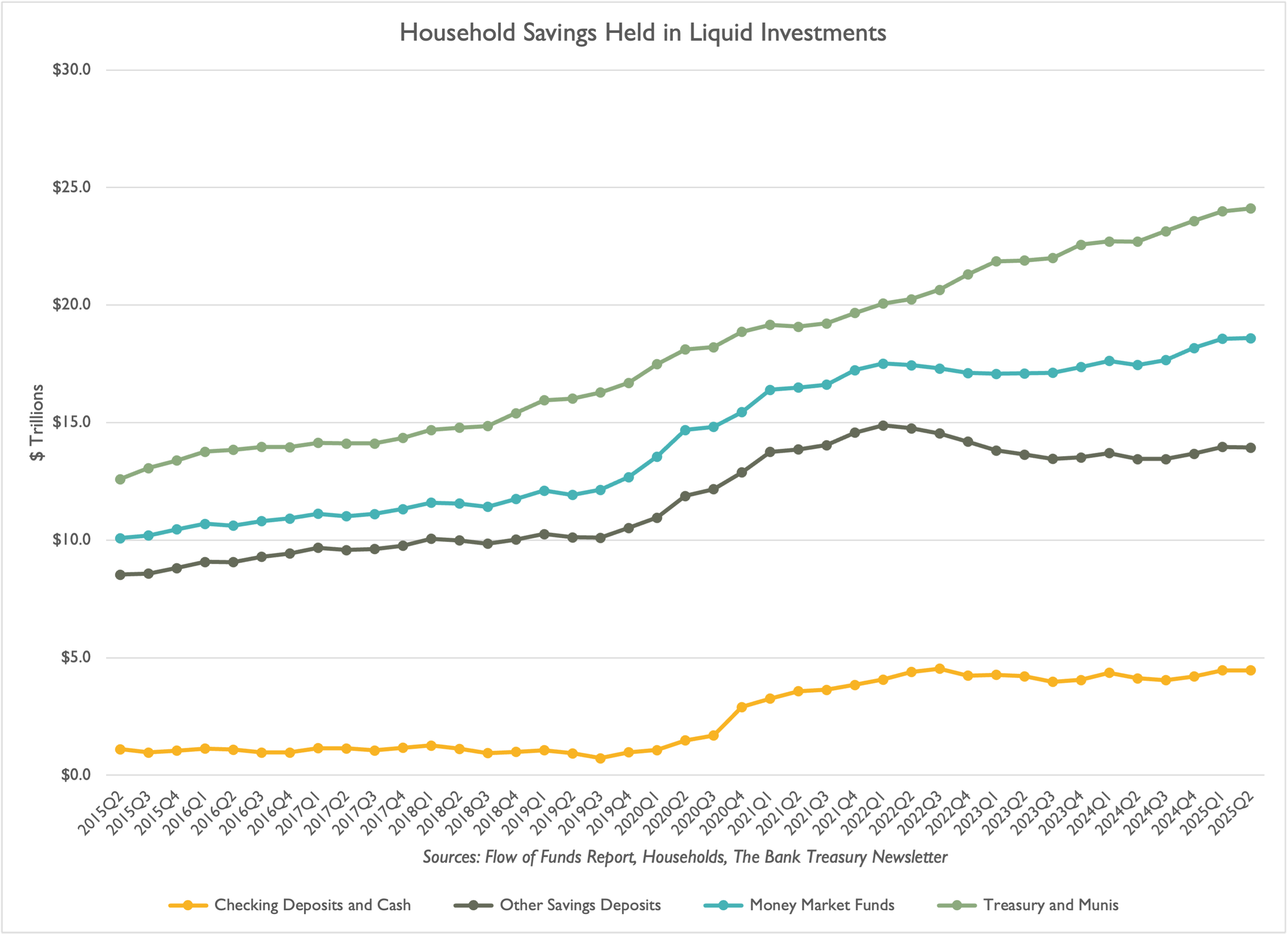

There are also broader trends to consider, as the CFO of a regional bank in the Southeast noted regarding deposit growth that deposits are competitive. H8 data (Figure 1) shows that deposit balances are growing and at a record high—over $17 trillion—but the industry is still losing out to money markets and other nonbank savings alternatives, which are growing faster,

“The deposits in the industry are shrinking…We mentioned in our last earnings call that we saw a mix out of money markets and we looked at where our clients are putting their funds, it was into brokerage accounts. And so I think the competition for deposits will continue to heat up.”.

Figure 1: Domestic Deposits Annual Growth Rate

Which leaves bankers wondering just like everyone else whether the data point they are looking at is just another dot on a line segment, or an inflection point and a new angle. As the CFO continued, she could not see a sign that deposit growth rates are reaching an inflection point,

“And if you look at this quarter, it's been strong with net new checking accounts this quarter. And so what you're left with is just the question of how that average balance per customer evolves and when you hit the inflection point of that number based on the factors that we've just gone through. And so at the margin, that kind of upward inflection point has been pushed out a little bit.”

Is a data point an inflection point, or an outlier, only the future knows for sure, but bank treasurers cannot wait for certainty, cannot wait for all the dots to make a call, is it a bird or a plane, or is it superman. Investment decisions need to be made now, prices need resetting today, the asset-liability committee needs answers immediately, and delay is no option. Decisions must be made. Because the Fed is set to cut very soon which could be costly in terms of NIMs and NIIs.

Routine is a bank treasurer’s friend. The trick with asset-liability management is to insulate the bank’s financial performance from volatile factors such as a change in monetary policy by the Fed. That buys time to see more dots and make a more informed decision. The CFO of a small regional bank in the southeast explained,

“From a margin perspective, we're well positioned. The rate cut in September so far has not impacted net interest income and margin. Rate cuts generally, if they're moderate and spaced out a little bit, shouldn't be harmful. I don't think -- if you recall back several years ago when rates fell dramatically and went way down, that's when everybody including us, kind of had some issues, losing some margin for a while, took a while to gain it back. But overall, I don't think that minor and spaced-out rate cuts would really be too impactful.”

Rate changes should have minimal impact on NIM and NII if bank treasurers are doing their job right. Right now, the most significant factor in those metrics is the roll-on, roll-off spread for new investments, where bank treasurers report reaching a point of rate relief. The balance sheet was rate neutral, according to the CFO at a large regional bank based in the Midwest,

“If you unpack the drivers of NIM expansion the biggest and most significant type of net driver is that fixed asset repricing…it's really driven foundationally by the roll-off yields…We're generally asset neutral…And so that really helps us to buffer the various scenarios in rate.”

If any rate change could directly tie to NIM and NII, it would be the shape of the yield curve, and in particular, the shape of the front end, which the CFO of a large domestic bank noted was still inverted,

“The curve from a SOFR versus five-year treasury is still quite inverted. If the curve becomes more upward sloping in that part of the curve, that could really help boost the speed in which NIM improves. “

The picture is confusing. Some might say it is grim. Charitably, one could describe it as complicated. The rate outlook is who knows; the economic outlook is possibly more uncertain than any Fed governor has ever seen it, and the number of dots that need to fit into whatever picture is emerging out of all this confusion is changing, whether bank treasurers should prepare for interest rates that are higher, lower, or unchanged. Consequently, they are busy hedging as much as they can as opportunistically as they can. The chairman and CEO of the same large northeast-based regional bank explained,

“Over time, we've been layering in hedges to protect the downside if the Fed cuts rates more aggressively. And so that's been a focal point. But again, we don't want to be wrong. We don't want to just concern ourselves with the Fed cutting more aggressively because we still have a lot of inflation, and we could stay sticky high. And so we haven't -- we've kept kind of a balanced view as to let's put those hedges on opportunistically when we see little spikes.”

Central Banking Dots

Central bankers ask themselves all the time: Is a surge in prices temporary, or is it something to really worry about that may force them to raise rates higher and faster again? Is it significant that company hiring is slowing down, or should we fret that people looking for jobs are looking less, or is the data faulty?

What to make of the picture emerging from the dots, they ask themselves every day. Theirs is a world where the data they depend on evolves, and its future path spans many possible scenarios and multiple inflection points; the picture they want to see is still clouded by what has not happened yet. Theirs is an uncertain dot plot with a wide range of dispersion (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Latest Fed Dot Plot

As Chair Powell said at a meeting of the National Association of Business Economics earlier this month about the FOMC’s latest projections,

“There is no risk-free path for policy as we navigate the tension between our employment and inflation goals. This challenge was evident in the dispersion of Committee participants' projections at the September meeting. I will stress again that these projections should be understood as representing a range of potential outcomes whose probabilities evolve as new information informs our meeting-by-meeting approach to policymaking.”

On watch for alerts, bank treasurers struggle with quirks in their models and contend with stochastic anomalies in their regressions. Even with all the dots that the voting members of the FOMC can see, the picture is still not obvious. Chair Powell knows well that it is no easy task to see in real time what in hindsight seems obvious. Reflecting on the time four years ago when the Fed ended quantitative easing, he conceded,

“With the clarity of hindsight, we could have—and perhaps should have—stopped asset purchases sooner.”

Today, he has reason to wonder whether he was late to end quantitative easing four years ago next month, especially now that he is considering ending QT. Some of the dots he has seen recently could be giving him some pause. For example, the rate on overnight general collateral repurchase agreements remained above the Federal Reserve’s rate for Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) thanks to the pressure from Treasury bill auction settlements. Banks and dealers have also been tapping into the Fed’s Standing Repo Facility, indicative of liquidity strain in the Treasury market.

Connecting dots in the repo market to the Fed’s balance sheet, Julie Remache, Deputy SOMA Manager and Head of Market and Portfolio Analysis on the Open Market Trading Desk, saw a picture that told her that the Fed may need to end QT soon,

“Our indicators currently suggest that reserves are still abundant. But we have observed some firming of repo rates recently, in part due to the increase in bill supply after the debt ceiling resolution, and continued pressures are likely over time given ongoing Fed balance sheet reduction. We have also started to see some movement in the distribution of Federal funds transactions in response to higher repo rates—which is a healthy sign of market linkages, and exactly what we would expect. Most recently, this has translated to a one-basis-point increase in the Effective Fed funds rate (EFFR) relative to interest on reserve balances.”

The dots can change in the real world, even for time-honored target rates such as the EFFR, which the Fed began targeting 30 years ago. As Lori Logan, Dallas Fed president, explained, the Fed funds market is not the same market it was in the 1990s, before the Fed expanded its balance sheet and ultimately eliminated required reserves. Today, the Fed funds market is nowhere near as liquid as it once was, and the relative importance of the EFFR compared to SOFR has shifted to the repo market. Hence, the Fed is thinking about changing its target rate from EFFR to the Tri-Party General Collateral (TGCR) repo rate. She favored that rate over SOFR because, as she explained,

“SOFR combines two main market segments: tri-party repos that take place primarily between cash investors and large dealers, and centrally cleared repos that take place primarily between large dealers and smaller ones or leveraged investors. Large dealers have some market power in intermediating between the segments, so rates in the centrally cleared segment can partly reflect market power rather than the cost of funds. The tri-party general collateral rate (TGCR) is cleaner, and I think it would currently offer the best target. It incorporates more than $1 trillion a day in risk-free transactions that represent a marginal cost of funds and marginal return on investment for a large number of participants.”

Part of the job of bank treasury is getting out and talking to people. There's probably no better way to gather intelligence than Google. Still, if that is no help because the Government stopped reporting, there is no better alternative than pressing the flesh with your borrowers and your depositors. Without the benefit of publicly available data, central bankers have also gone out to press the flesh and ask people directly what they think. As Fed Governor Chris Waller told the Council on Foreign Relations this month,

“To deal with this lack of public data, I spend a lot of my time talking to business contacts, whose views help me to form my outlook for the economy.”

And even after all that effort, connecting the dots is still very difficult today because every data point conflicts with another. The dots do not look like any picture that makes sense. As Fed Governor Waller told the Council on Foreign Relations in a speech earlier this month,

“So far that input tends to support—rather than resolve—the contrast we have seen between strong economic activity and a softening labor market. Employers indicate to me that there was some further softening of the labor market last month, while retailers report continued solid spending, with a bit of caution from lower-income households…I see a conflict right now between data showing solid growth in economic activity and data showing a softening labor market. So, something's gotta give—either economic growth softens to match a soft labor market, or the labor market rebounds to match stronger economic growth.”

Economic data is fuzzy, but imprecision goes with the territory. And the stakes are high if the data is misread. As Fed Governor Waller put it,

“Since we don't know which way the data will break on this conflict, we need to move with care when adjusting the policy rate to ensure we don't make a mistake that will be costly to correct…While there are times when the data are consistent and paint a clear picture, the economy is vast and complex, and it is quite often the case that some of the data we look at will point in a different direction from other data and make that picture of the economy fuzzy. Almost every month, I need to use some judgment in sifting signal from noise in the economic data—it is just part of the job of economic forecasting and policymaking.”

According to Lori Logan, the picture she sees emerging is three-dimensional. Speaking to participants for a Fed survey late last month, the picture she saw was one without many more rate cuts,

“As I consider the path ahead, three features of the economy stand out to me... First, even setting aside temporary effects of this year’s increases in tariff rates, inflation is not convincingly on track to return all the way to 2 percent. Second, aggregate demand remains resilient, supported by consumption, business investment and buoyant financial conditions. Third, while the labor market has undeniably slowed, with meaningful costs to workers, not all the weakness represents economic slack that less-restrictive monetary policy can ameliorate.”

But that is not the way Fed Governor Stephen Miran sees it, who wanted a 50-basis-point cut last month and expects the FOMC to cut again on October 29 and again at the meeting in December. Even if not all the data is available to base a decision about rates, the picture he sees demands action,

“It would be helpful to have the economic data to make the decisions we need to make. Certainly, we would want to inspect the economy for signs of moves lower in inflation, for signs of changes in the job market. But without those data, we still have to make a decision anyway, and so we’ll have to rely upon our forecasts for doing so.”

AOCI Dots Stubbornly Remain

Stepping back from the noise, bank treasurers try to see the big picture, read the tea leaves, and map out where they see long-term trends going. They look past the day to day gyrations in the market, where mortgage rates this month are the tightest they have been in three months but more generally the lowest they have been in three years. They recall that they booked their bond portfolios and fixed rate loan books earlier than three years ago, which are now laden with 2% and 3% coupons and still carry the weight of negative Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI). As the president and CEO of a small regional bank in the Midwest told analysts, AOCI remains a challenge for mergers and acquisitions, notwithstanding the multiple acquisitions in the market going on today,

“I would say that we still have the overhang of the AOCI that's keeping some sellers on the bench. It's a slow boat to China. And it's not just the AOCI in the bond portfolio, but there are -- it's disappointingly surprising how many bankers booked really long maturity and lower fixed rate loans and it's just going to take some time to work out. So that has a dampening effect on -- the sellers, they all think they're worth fill in the blank, whatever. They all think they're worth 1.5 times to 2 times. And when you factor all those purchase accounting marks into the equation, it makes it more difficult.”

The good news is that lower rates are fueling a wave of refinancings. According to the Mortgage Bankers Association index, refi demand was up 81% last month compared to September 2024. The bad news is that the number is off a low base and could just be a blip. Even at three-year lows, there is no wave of first-time borrowers forming to dilute existing earning asset concentrations in low-returns on bank balance sheets, no refi wave coming to take them out of their underwater fixed-rate loans. As the president of a large regional bank based in the northeast noted,

“If you look at the US homeowner right now…74% of the country has interest rates under 5% on their mortgage. And so you'd have to believe a whole lot to have a massive refi pickup here with rates having a six handle on it now and the long-term rate is relatively stable.”

Other Worrying Dots

Bank regulatory rollback is another dot or set of dots in the picture. Whether this is a good thing or a bad thing depends on the perspective. Managers at the largest banks regularly complain that regulators keep layering rules on top of regulations, buffers on top of buffers, capital for credit risk, interest rate risk, liquidity risk, and operational risk, without considering that the requirements could be overlapping and over-punitive.

Bank supervision is an endless struggle to balance focus on fundamentals and process. Banks might get into trouble over bad loans, but with enough capital on their balance sheets, those losses become immaterial to their financial condition. Lenders to First Brands and Tricolor are not facing ruin. The worst fallout from the episode was their embarrassment at being stung.

But the faulty underwriting that led to First Brands and Tricolor might be linked to poor risk management and governance issues. Maybe these episodes are cockroaches. Shining shoes, dotting the I, and crossing the T might seem irrelevant to avoiding more significant problems, but often good process leads to good outcomes, as compliance lawyers would say. On the other hand, bank supervision is not immune to going overboard.

So, regulators are recalibrating their approach to keeping the nation's banking system out of trouble. The FDIC and OCC, for example, raised the bar for issuing enforcement actions to focus on so-called safety and soundness issues. Notices for deficiencies, such as MRAs, must focus on actual violations, not merely potential ones. They also pledged to focus on material issues. FDIC and OCC examiner suggestions are nonbinding, and regulators will downgrade a bank's composite rating only for reasons tied to material financial risks. Reputation risk is no longer a thing.

The chairman and CEO of a global bank applauded the bank supervision's back-to-basics focus on bank balance sheets, rather than a no-refi wave to take them out of their underwater fixed-rate loans. As the president of a large regional bank based in the northeast noted,

“We had Silicon Valley Bank blow up because they're so focused on governance, they forgot to focus on interest rate exposure. And they are making changes that focus on what is actually the real risk that banks are bearing.”

According to the chairman and CEO of a large domestic bank, bank supervision has gotten bogged down in paperwork. The notices for MRA and Matters Requiring Immediate Attention (MRIA) may have been well-intentioned at first, but have now become make-work exercises. Bank supervision could save banks significant time and money if the process were less formal. Sometimes, an MRA or MRIA should just be a suggestion and not a requirement,

“The MRA proposal if it does nothing else, will get rid of all the crazy work we do on minor MRAs…If we get an MRA -- and by the way, we get a lot of them for kind of silly reasons--you have to…negotiate it with the regulators, that's a team of people, then you write your response to how you're going to fix the MRA, and then you assign people who are responsible for the MRA and then you set up committees, and then you spend 1,000 hours…You could actually fix the issue that they were concerned about in 10 hours.”

Streamlining the regulations that have gotten out of hand may not result in specific headcount reductions, but it will at least free up staff time to focus on their day jobs--making money for the bank, according to the CFO at a regional bank on the East Coast,

“When you had a review, you get observations. And then if it was more serious, you might get an MRA, or something really serious, an MRIA…You have a year to get it fixed before they come back…And…by just having a recommendation to do something, you don't have a whole process…that you have to do when you're trying to fix a MRA or MRIA. So just that itself, the timeline to get it done a lot faster, a lot less people working on it. As far as how much that actually reduces in head count and all that, I think it's -- definitely will be less people needed in the remediation areas. We'll probably try to redeploy folks in other areas…because those people are experienced people that you want to keep in the company.”

The chairman, president, and CEO of a large regional bank based in the Midwest added that coordinating exams between the different agencies, between the Fed, the OCC, and the FDIC, will also help free up staff time bogged down in endless meetings with bank examiners covering the same material,

“Since the GFC, there was a lot of layering of regulation on regulation, a lot of focus on process, a lot of focus on procedure, and a lot of focus on documentation. And I've been really pleased with what has been a dramatic change in that just a refocusing on safety and soundness, on liquidity, capital and earnings. The other thing is the regulators are…coordinating…exams so that we can do them concurrently as opposed to consecutively. Getting rid of some of the duplication, lets our risk teams focus on the risks…as opposed to preparing for exams, going through exams, and wrapping up exams.”

But still other dots complicate the picture. In the last quarter, Congress passed the Genius Act, which lets banks and other approved financial institutions issue their own coins. Stablecoins, instant payments, and the whole move in markets to same-day settlement create the potential for significant disruptions in the financial industry.

Bank treasurers worry that the crypto market will siphon deposits from the banking system, especially if nonbanks take advantage of loopholes they worry exist to offer interest-bearing stablecoins, which the GENIUS Act bans. Jonathan Gould, the Comptroller of the Currency, tried to allay their worries in a speech this month to the American Bankers Association, telling them that deposits would not leave the system overnight,

"It would not happen in unnoticed fashion…would not happen overnight…If there were to be a material flight from the banking system, I would be taking action."

According to Eugene Ludwig, Mr. Gould’s earlier predecessor from the 1990s, something is coming, but it is nothing new-fangled like stablecoins. As he wrote this month,

“This is what Wall Street neglects — and what policymakers cannot afford to ignore. Betting against the market may be risky, but for Washington, betting against the economic well-being of most Americans is reckless. If these trends continue, we are headed into a serious economic storm. Early warning signs are everywhere. Food-bank networks report record demand, even in states with low official unemployment. Credit-card and auto-loan delinquencies have climbed back to levels last seen before the 2008 crisis. And surveys show nearly 60 percent of Americans don't have enough savings to cover an unexpected $1,000 expense.”

Unfortunately, history shows that what bank treasurers really need to worry about is what may be staring them straight in the face, but that they do not see, even with numbered dots. The dots in this picture might connect and still not show anything, but maybe bank treasurers just need to learn to look harder.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2025, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief

This Month’s Chart Deck

Lending to non-depository financial institutions (NDFIs) was a buzzy acronym that popped up during this month's quarterly bank earnings calls as a potential source of credit risk. The term, however, encompasses many different business sectors and borrower quality. However, since the Fed began tracking the number in the H.8 report in 2015, loans in that category shot up to $1.7 trillion this month, a 60% increase over the last year (Slide 1). Bank managers also reported healthy loan growth. Still, banks surveyed in the previous Senior Lending Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS) report, released last August, did not report any tick-up in demand for Commercial and Industrial loans (Slide 2). The consumer remains healthy, with unemployment holding steady and the participation rate back to near historic highs (Slide 3).

While the H.8 data shows that the banking industry’s deposits at over $17 trillion are higher than they were before the Fed began to hike interest rates in March 2022, the bigger picture is that the industry is steadily losing share of household savings to the money market funds (MMFs) and TreasuryDirect.Gov where they can buy Treasurys directly through their checking accounts (Slide 4).

The voting members of the Federal Open Market Committee meet this month to decide on another 25-basis point cut in the Fed funds rate have a touch decision ahead of them, blind on much of the macro-economic data they depend on to do their jobs because of the Government shutdown, Fortunately they have other sources of information from the 12 reserve banks which help to fill in the missing data. For example, the New York Fed publishes consumer inflation expectations for 1-year and 3-year (Slide 5), which supports the thesis that inflation is falling. But then the inflation number last month pops up to 3%. The data is conflicting.

Treasury's new issuance is adding to financial stress in the system, which has caused a sharp increase in outstanding repo over the last 12 months (Slide 6). On the other hand, amid uncertainty from tariff policies and the shutdown, market indicators also support the thesis that all is well in the financial system. The Office of Financial Research's financial stress index remains well anchored at 0 (Slide 7), while the probability of a recession remains low according to the New York Fed's recession probability index (Slide 8). Credit delinquencies in household debt are higher, normalizing from ultra-low levels (Slide 9), but corporate bond default risk remains as low as it has ever been over the past 20 years (Slide 10).

NDFI Lending Volumes Go Exponential

C&I Loan Demand Slows

Employment Participation Fully Recovered

Household Savings Mix Shifts From Bank Deposits

Inflation Expectations Remain Unchanged

Outstanding Repos Up Nearly 60% Last 12 Months

Financial System Stress Remains Normal

Probability Of A Recession Down

Consumer Delinquencies Continue To Normalize

Corporate Defaults Hold Near 20-Year Lows