BANK TREASURERS ARE THANKFUL FOR PENNIES

Bank supervisors proceeded with their plan to ease capital requirements for the most prominent institutions and submitted a set of alternative proposals to the President for review and consideration. They propose to reduce the burden of the enhanced Supplementary Leverage Ratio (e-SLR), which large banks complain impedes their capacity to support the Treasury market, including the repo market. Volatility in the Treasury repo market is noticeably higher than it has been in the last year and in the previous few months during the shutdown that just ended. Bank supervisors are worried that the banks are running into capacity problems given the growth in the Treasury market in the last decade, with outstandings going from $12.5 trillion in 2014 to $32.0 trillion this year, while banking industry assets only grew from $14.4 trillion to $24.4 trillion.

One of the proposal’s features would adjust the calculation of the e-SLR’s denominator to exclude Treasury securities held in trading accounts for Category 1 and 3 banks. Their plan would offer some regulatory relief with respect to the e-SLR, cutting the capital requirement for Category 1 banks on average by 20%-30%. However, large banks would still be subject to additional capital requirements for market, interest rate, and operational risk, would still need to pass the annual stress tests, and would still be subject to Basel III liquidity requirements, including the Liquidity Coverage Ratio and the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR).

The NSFR, which matches an institution’s long-term assets with long-term liabilities, is especially challenging for banks engaged in the repo market, which underpins Treasury market liquidity. Bank supervisors currently have no plans to change these requirements, but rather to reduce the degree to which the e-SLR is a binding constraint on large banks in supporting market liquidity, especially in the Treasury space. Bank supervisors gave large banks temporary relief from the e-SLR with respect to holding Treasurys and reserve deposits during Covid to help support market liquidity, and they believe that their proposal would be beneficial given the current strains they think they see in the market. In other news, which will also help improve liquidity in trading markets, the Fed finalized plans to expand the Fedwire from 22 hours a day, 5 days a week, to 22 hours a day, 7 days a week.

The Treasury repo market continues to show signs of stress, with rates for general collateral repo trading over 4% this month, above the top of the Fed’s policy range for the Reverse Repo facility (RRP), which it cut on October 30th to 3.75%. At the end of last month, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) reached 4.31%, and this month it has frequently spiked over 4.00%. By contrast, until last year, SOFR was generally in line with the RRP and at times a couple of basis points below it. Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) officials believe that the trading pattern with repo suggests that they achieved their objective to reduce reserve deposits from a level they describe as “abundant” to one that is “ample.” Therefore, they plan to end Quantitative Tightening (QT) next month.

However, despite the focus on QT’s impact on market liquidity, the main stress came from the government shutdown, which caused the Treasury General Account (TGA) balance to increase by nearly 50% since last September, from $650 billion to $950 billion, which put direct downward pressure on reserve deposits, which fell from $3.1 trillion in the beginning of September, to $2.8 trillion two months later. Notably, despite respective caps of $5 billion and $35 billion on its System Open Market Account (SOMA) Treasury and Agency MBS holdings, SOMA only fell $35 billion over the two months, from $6.31 trillion to $6.26 trillion.

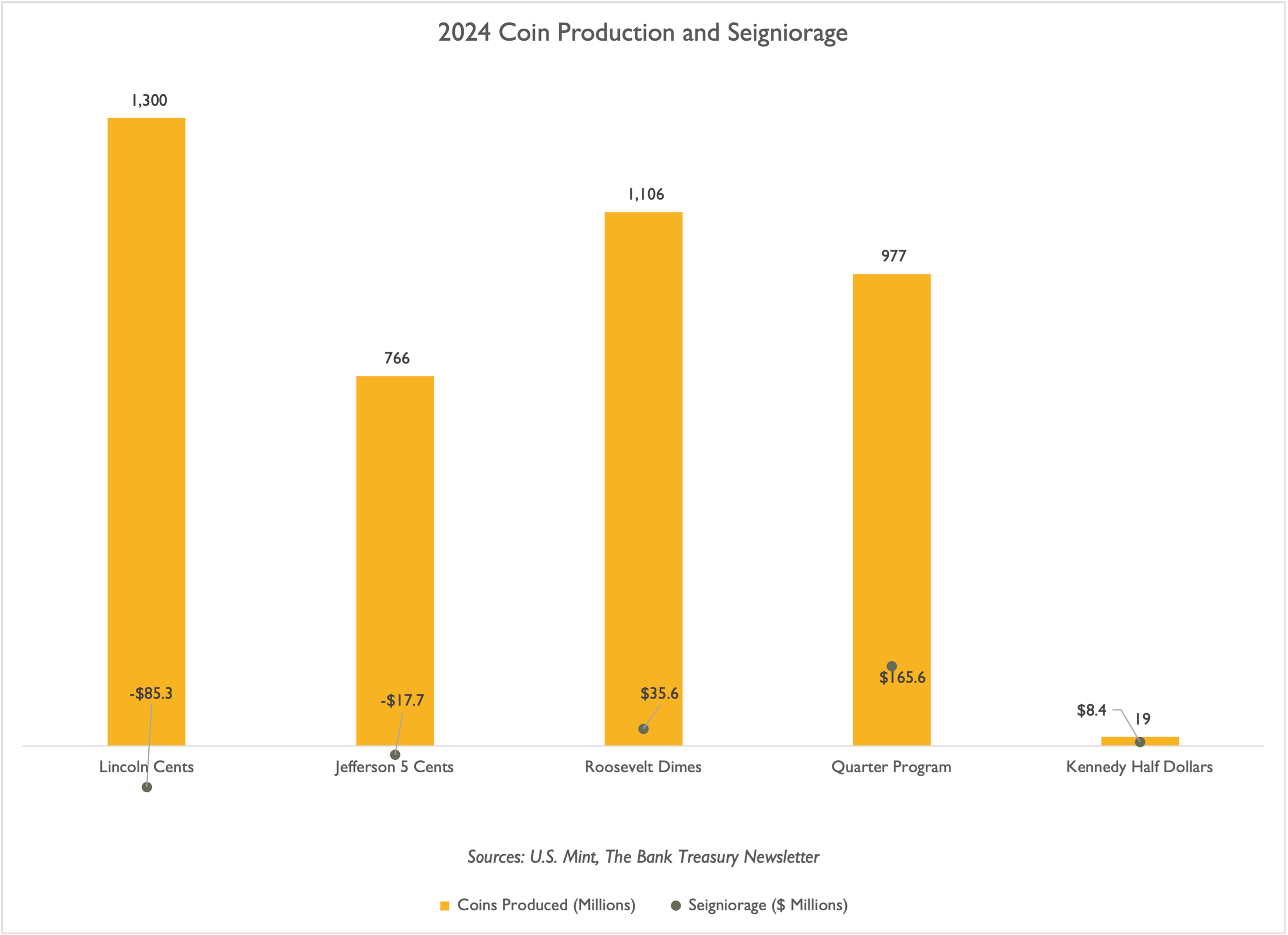

After more than 25 years of calls by both Democrat and Republican politicians for its end, the President of the United States ordered the Treasury this year to stop making pennies, the oldest coin minted by the government. The U.S. Mint coined 3.2 billion pennies last year and spent nearly four cents to make one penny. The penny and the nickel are the only coins the Mint produces where it regularly loses money on seigniorage, with recent years topping $100 million a year; most of the loss comes from the penny. Notably, survey after survey finds that the public has long regarded the coin as a nuisance. Aside from leaving them in mason jars and desk drawers instead of using them, which returns them to circulation, they will sometimes simply discard them.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

You heard about the business with the pennies, right? The U.S. Mint stopped making them. Policy experts have been discussing the penny problem for years, but finally, someone took action. Back in February, Trump ordered the Treasury to kill it (or, perhaps a better description would be: “retire it”), supposedly while he was watching the Super Bowl halftime show. Or maybe while he was coming back from it, who knows, with the information you get on social media these days, where he made the announcement. In any case, so, yeah, that happened.

Last May, the Treasury followed through, and the U.S. Mint purchased its final shipment of copper-alloyed zinc blanks to make pennies from, marking the end of an era—bye-bye pennies. In fact, there are already reports of shortages, and the situation is only going to get worse. Perhaps even worse than the flight delays caused by the recent shutdown. But the pennies, Man! Telling ya, people are going to start rioting in the streets over them, you will see.

Fun Facts

Hey, fun fact. Did you know that the penny is the oldest coin the Mint has been producing continuously since 1793? Amazing! However, the Pilgrims (this month's newsletter is our annual Thanksgiving-themed edition, so they deserve honorable mention here) used pennies, which they called pence when they were not using barter or wampum. And, they even used half-pennies, because that was the currency they took from England.

Can you imagine being in a checkout line buying groceries, and the person ahead of you started counting out half-pennies if they existed? OMG! It's bad enough that you still have people paying with cash, counting out every penny, holding up the line, and wanting exact change. By the way, half-pennies are no joke. The U.S. Treasury had them in circulation until 1857, when it eliminated them. Who is going to be laughing now? Dum, de dum, dum, da!

Come on, we are talking about Abraham Lincoln heads and the Lincoln Memorial tails! The dude created Thanksgiving, or at least made it a national holiday. Who knows what he might have gone on to do had he not been assasinated. Maybe make Black Friday an official day off, too. He was the guy responsible for the OCC and national charters, the banks that have the initials N.A. after their name that stands for National Association. His coin going out of style almost seems metaphorical considering what is going on in Washington these days. How can bank treasurers out there reading this just shrug? The end of the penny is definitely worth more than that, even if a penny is not worth much.

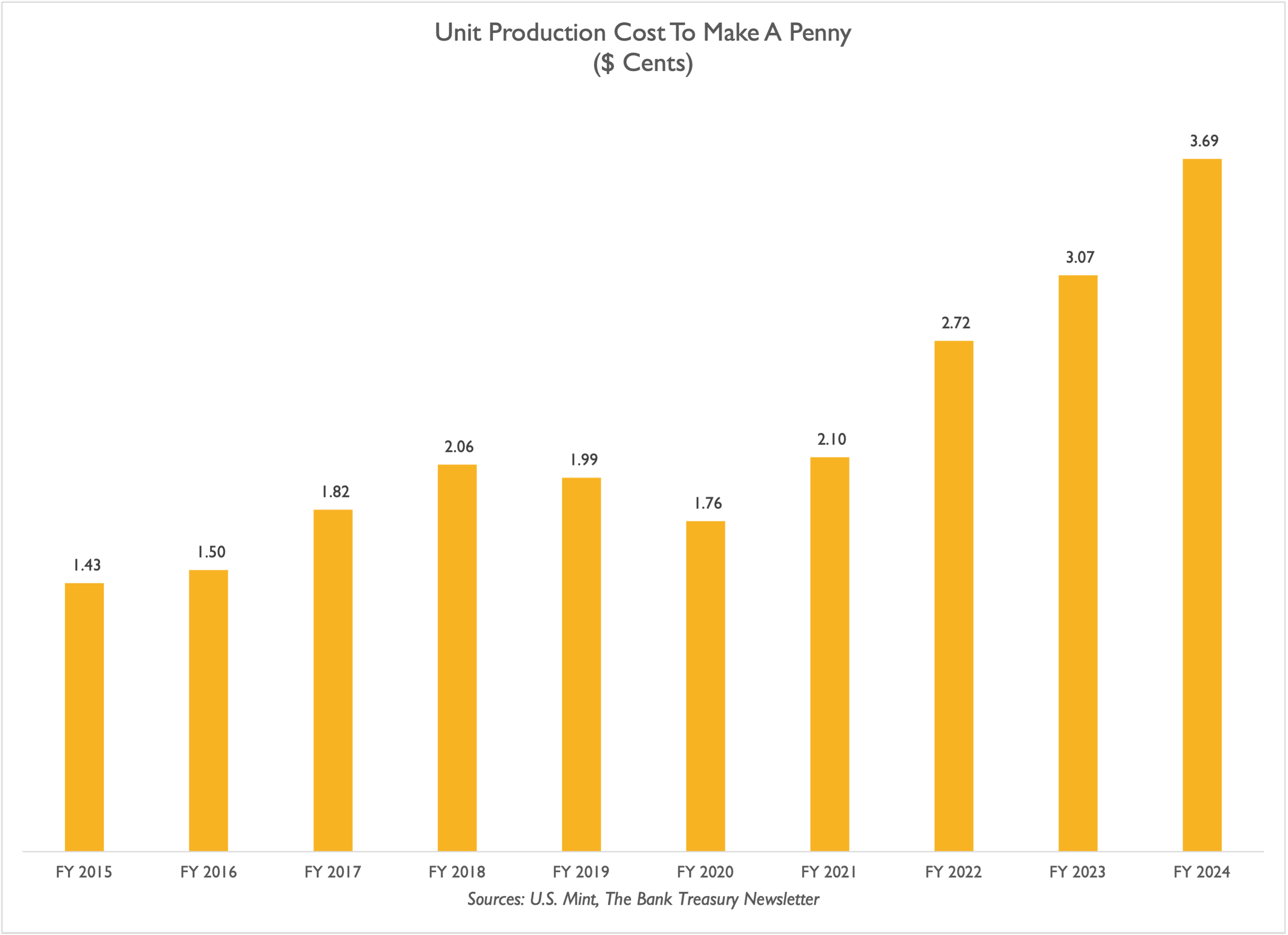

Do you know what is crazy, though? There is a lot of wild stuff with the penny story, but the craziest thing is that one pennycosts 3.69 centsto produce. Right, isn’t that crazy? Let’s do the math. Through the end of October, the U.S. produced1.3 billion pennies, which should have cost $48 million to create, but were worth only $13 million. Outrageous, right? But this is nothing compared to what it must have spent on making pennies in 2024, when it minted 3.2 billion, or before Covid, when the Mint was coining 8 billion pennies a year.

So, going with 3.69 cents a penny, before Covid, the Mint might have spent $300 million a year making pennies. That is a lot of money for pocket change! People might still have sentimental feelings for the pseudo-copper coin, but not when you are talking about a nine-digit budget to produce it. However, on the other hand, it is still not a significant amount of money when considering the growing multi-trillion-dollar deficits and government debt, which this year topped over $38 trillion.

With paper money in circulation climbing this year to over $2.4 trillion, pennies are not even a rounding error in a budget equation. You could pinch every penny you find for the rest of your life, and a hill of beans would be worth more! But maybe every penny matters when we just saw the most extended government shutdown over the budget deficit since the Mint started producing pennies.

Picture the scene. The Eagles had pretty much shut out Kansas City by the halftime show. Kendrick Lamar came out and was in the middle of singing “Humble,”

“Nobody pray for me, it been that day for me.”

And Trump, announcing the end of pennies, clacked out on his phone,

“Let’s rip the waste out of our great nation’s budget, even if it’s a penny at a time.”

More fun facts. According to the American Bankers Association, there are 250 billion pennies in existence. Each one may weigh no more than 2.5 grams. But put them all in one pile and you are talking about 625 billion grams, or 689 tons.

Most of them are not really in circulation. Most of them are either in mason jars like the one pictured above, a drawer, or maybe like murdered dead bodies buried in a landfill. Do you know the leading reason why people with mason jars full of pennies do not take them to a bank and redeem them for bigger bills? They weigh too much and are not worth the effort. Easier to pull out a credit card and buy a new mason jar to hold more pennies, or repurpose an old coffee can.

And, oh yeah, people really do throw out their pennies. Yes, really! Check out the pie graph on page 13 in this Richmond Fed 2022 study. They throw them out, but they are reluctant to discuss it. Throwing out pennies, just leaving them on the street and walking away, is like abandoning a pet in the park, or a newborn at the firehouse. People do it all the time. They just do not want to admit it.

Whatever, who knows. Pennies are, let’s say it, a nuisance. Raise your hand if you pay with a credit card for a small transaction rather than getting hit with some of these coins to jangle around in your pocket or purse until you find someone else to dump them on. By the way, it is your right to refuse pennies as change. Charity boxes are all about pennies that no one wanted but did not have the courage to face their moral failings and discard. That is right. Getting rid of pennies is going to really hurt charity box collections.

Pennies are a burden. Maybe having one is suitable for buying one-cent candy, but shelling out coins, counting them, and then carrying the jingling things is a pain. And how about taking all your coins out to go through a security gate? Who wants to be busy with that? Economists at the Atlanta Fed believe that eliminating the penny is a good idea, but perhaps not as effective as it could be, because merchants are already rounding prices to the nearest nickel anyway. The penny is already gone.

It is bipartisan to be against the penny, even if the economically most disadvantaged, underbanked, and unbanked, when they are not using money orders, are thankful to count out every penny when they buy their daily bread. But the Kill Bill effort is a long-standing political tradition in Congress, going back to the “Price Rounding Act of 1989,” H.R. 3761.

Last April, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, a Democrat from New York, joined colleagues from both sides of the aisle to push for the latest version, the “Common Cents Act of 2025,” and declared in a press release introducing the proposed legislation to eliminate the penny,

“The penny is outdated and inefficient and no longer serves the needs of our economy. By suspending its production, we can reduce government spending, streamline transactions, and move toward a more practical financial system. It’s time to invest in a future that works for the 21st century economy, and that starts with suspending production of the penny.”

Cynthia Lumis, Republican Senator from Wyoming and co-sponsor, boldly agreed with the President of her party,

“I agree with President Trump that the time has come to fully end production of the penny and save American taxpayers money. The fiscal reality is undeniable: the U.S. Mint spends three cents to produce each one-cent coin…we have to implement meaningful opportunities to reduce costs, update our currency system, and codify the elimination of government inefficiencies. It just makes cents!”

Rounding Tax

But everyone still uses cash, so everyone still needs to care about pennies, even bank treasurers with a lot more problems on their hands than what they can carry in their pockets. The Atlanta Fed’s consumer payment survey found that cash use is on the decline, but it still accounted for 14% of consumer purchases in 2024. Additionally, 83% of consumers surveyed reported using cash to make a purchase in the last 30 days.

Getting rid of pennies will make for some hard choices at the cash register for people who like to pay with cash, because paying with it is a losing proposition when it comes to pennies. Rounding never works in the payer’s favor. Ask the Canadians, who said goodbye in 2012 to their maple-leaf-twigged coins.

Let’s say you need to pick up a gallon of whole milk on your way home. According to FRED, the cost of milk is $4.13. Perhaps you pick up a dozen eggs while passing through the dairy aisle, which costs $3.49. Finally, on your way to the checkout line, you remember you need white bread and grab a pound of it, which costs $1.87. Your total comes to $9.49, and no sales tax is involved because you only purchased food staples.

The price is right, but without pennies in the world, you will need to think strategically. No purchase will be simple anymore. You could just eat the penny and pay $9.50 for the milk, eggs, and bread. Or you could leave something with the cashier at the register. Leaving the bread, for example, would be great from a penny perspective because it would bring your total down to $7.62, and rounding down gets you two extra pennies. On the other hand, leaving the eggs would bring the total to $6.00, which is even. The only thing you do not want to do is just buy the milk, because then you will need to pay $4.15 and eat two pennies.

Of course, if after waiting for the person ahead of you to count out every stupid coin in their change purse, you could not resist the impulse purchase to splurge on the latest $6.99 edition of People magazine, there would be some sales tax involved. In New York City, the tax on the magazine would bring its full cost up to $7.61, and your total at the cash register would be $17.10, which would be a great outcome penny-wise, but ounce-wise, foolish. Paying with cash would mean you get back 90 cents in change to carry around in your pocket, a lump of quarters, dimes, and nickels all together weighing about a full ounce.

That will be the new rule going forward, the rounding rule. If you pay cash and you do not have pennies, you round up to the nearest nickel when the last digit in the price is 3, 4, 8, or 9, and round down when the last digit is 1, 2, 6, or 7. And here is another fun fact. The way merchants set prices means you will end up rounding up more than you will be rounding down. The rounding rule will result in a tax on rounding, which will cost U.S. consumers approximately $6 million per year. Talk about rounding errors!

But rounding is not so simple. Let’s say you are the newly elected mayor of the City of New York, and you want to raise property taxes on landlords to fund your new transportation program for people who count their pennies as their life’s savings. A landlord comes into the tax office carrying cash to pay a bill, which, by law, is based on multiplying a specific rate by the assessed property value. In the landlord’s case, this comes to $XXX, XXX.02. Without pennies, the clerk and the landlord are in a predicament.

First of all, if you are the government, you cannot tell a taxpayer that their cash is no good. Cash is legal tender for all debt, as it says on the money, and that applies to New York City and its socialist-minded mayor, too. The clerk must accept cash, regardless of whether they have any change on their desk or in mason jars. But in no world does the landlord round down and not owe the two cents. The landlord is going to get shaken down for every penny owed.

So, if the clerk has no pennies for change, the landlord’s choices are either to eat the three cents or pay some other way that does not involve cash, such as by check, credit card, ACH, and possibly one day even by stablecoin. The clerk cannot simply round down, change the amount due, and eliminate the two cents on the tax invoice as per the rounding rule, even if the law were to change to allow the clerk to accommodate penniless landlords. That would be akin to the clerk offering a cash discount, which would not be fair to most landlords who do not pay by cash and would waste the clerk’s time making change.

It could get worse and more complicated. Let’s say a business owner comes in to pay taxes, and that business owner can only pay cash. Say, it is one of those cannabis stores in the city responsible for that unique smell in the air around Midtown Manhattan that cannot get a bank account and can only pay in cash. If the business owner needs to pay two cents in taxes on top of the nickels, dimes, quarters, half-dollars, and dollar coins owed, and rounds up to the nearest nickel, does the clerk enter a tax credit for three cents, or what?

Miss Them When They Are Gone

Are you getting mad yet? Or wondering what pennies really have to do with your bank treasury world? Leaving aside the fact that your bank takes coin shipments from the Fed to distribute to the public at large and then sends them back to the Fed when the public brings them back in for the paper equivalent, and ignoring the fact that most treasurers and CFOs have some operational responsibilities on their plate, you probably do not have time to think about small change like pennies. But you should.

Can you imagine, though? Ironically, the new limit on FedNow instant digital transactions is up to one penny less than $10 million. The end of the physical penny means mass extinction for an entire lexicon of idiomatic expressions no one will ever say again, because no one will even have these things anymore to think of the word.

No more penny pinching, penny-ante, lucky pennies, or bad pennies. A penny saved will not be a penny earned if there are no pennies. No one will offer pennies for your thoughts, tell you that you are being penny-wise and pound-foolish, accuse you of being so mean you would steal a penny off of a dead man's eyes (weird one, right?), or be worth every penny, or not have a penny to your name, much less two pennies to rub together.

What will you put in your penny loafers, or in your wishing wells? What will Penny Pockets do? How will we remember the Beatles' "Penny Lane?" How will you be in for a penny, in for a pound, or count on pennies from heaven, much less count them at all? How will you give anyone your two cents, or keep your two cents to yourself, when you do not even have one cent? There will be no pennies to put in the slot and wait patiently for something to happen, as Winston Churchill once said when Great Britain still had pennies in circulation,

“We are told at every turn that we must hand matters over to experts of all kinds. It reminds me of the machines in the railway stations and outside post offices. Put a penny in the slot, the machine does the rest. Well, we put our penny in the slot and nothing happens. And all we can do, so we are told, is to go on putting in pennies and being patient.”

And nothing will happen when all the pennies in the world amount to so little. A person could pick up pennies for a lifetime and not have much to show for it. Bank tellers will not even take them unless the customer already put them in paper wrappers, which cost $15.99 for a box of 1,000 online when you pay with a credit card.

Pennies, Repo, and a Steamroller

Forgive the shameless, but as our readers must admit, a clever transition to more pressing issues in the bank treasury world. Thus, when pennies are all lost in mason jars, drawers, and landfills, repo traders will need to find something else to pick up other than pennies in front of a steamroller. Because trading repo is basically a riskless business, most of the time. Bank treasurers have cordial relations with repo traders who frequently call into their funding desks, seeking overnight cash or collateral, but worry constantly that when things go wrong, the consequences can be severe. That is when repo traders get flattened.

Repo is simple and low risk. Technically, I sell you securities and simultaneously enter into a forward purchase agreement with you for the securities at a price that reflects both the funds you paid me plus interest for the term of the repo. Economically speaking, I give you a financial asset as collateral for a short-term loan based on its fair value at the time of the loan. During the term of the repo, you may hold my financial asset, but I still earn the interest on it. At maturity, I repay the loan plus an amount equal to the computed interest rate on the loan, and you return my financial asset.

However, even the most risk-free trade is not entirely risk-free. It does not take just a Global Financial Crisis (GFC) to expose the vulnerabilities in the system and unleash that steamroller. All it takes is a slight panic to grow into a bigger deal. Repo is about trust. A trader’s word is their bond, and trust, as veteran repo traders know, can evaporate very fast in the repo market.

A $12 trillion repo market is a massive steamroller. Settlement risk is a key vulnerability in bilaterally cleared repo, and an increase in fails is a harbinger of worse to come. Currently, failures are up a bit but not to levels last seen when the GFC hit or when Covid struck. Regulators would like to keep it that way. Market regulators are pushing to get all repo centrally cleared, even “specials,” to help reduce the steamroller risk in the trade by the end of June 2027. However, even after that deadline, not every repo will clear through the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation, for instance, if one of the counterparties is a local government still struggling with a lack of funds.

The repo business requires trust, and trust cannot endure without information. I know just enough about your financial condition to sort of trust that you will not go belly up on me before the repo matures. You know just enough about mine to make the same determination. The only thing you, as the lender, do not know about me when I repo bonds to you and you lend me cash, is whether I actually own the bonds I used as collateral or whether I am rehypothecating Treasurys owned by another counterparty transferred to me in a repo. And because you are unaware of this key detail, if you have any concerns about whether I will repay you, given that my counterparty could go bankrupt, you will not lend me money. Doubts can have a profound cascading effect on the health of a market that turns on trust.

One of the reasons repo market participants are exploring ways to tokenize repos is that it would address the trust issue, especially when using programmable tokens. Settlement issues are a critical stress level for repo. Figure out a way to make the settlements, and you take away stress. That is tokenization. These tokens relieve counterparties of wondering whether they will follow through at maturity to swap cash for collateral, as the coin contains all the information about the asset and its ownership. To have is to hold and to own.

The downside, however, as New York Fed economists discuss here, is that not all transparency is beneficial. If you know that I am short the market and need to cover, your offer might reflect your understanding of my desperate circumstances, you would otherwise not offer in a blind market. And fails to deliver can be strategic. If I worry about liquidity, I may decide to bear the cost rather than part with the asset I am holding.

Bank treasurers are fundamentally like repo traders working in a low-risk space to generate income for the bank, utilizing balance sheet and leverage to intermediate between borrowers with calculable risk and savers who could withdraw all their deposits from the bank in an instant. Repo traders make pennies in match-book repo by using their balance sheets to intermediate between a non-depository financial institution, such as a hedge fund, looking to finance bonds it has bought, and an asset manager looking to the repo market to park cash overnight. They are borrowers for every lender and lenders to every borrower, and make about as much on each matched book trade as royalty in the Middle Ages used to make from clipping coins.

Basel 3 capital rules, including the enhanced Supplementary Leverage Ratio and Net Stable Funding Ratio, have significantly reduced the profits in the repo business, and repo dealers are more selective about the counterparties they are willing to intermediate using their balance sheet as a result. However, the business still generates consistent, low-risk returns, even if trades are not particularly capital-friendly from a regulatory standpoint.

Repo is supposed to be low-risk because the market primarily runs on Treasury collateral, as the New York Fed’s primary dealer statistics attest. If, for some reason, I am unable to repay the money I promised to pay you back, you should not have too much trouble recovering your investment after selling my collateral in the market, which is generally stable and liquid. If you go bankrupt holding my Treasury Bills, I can use the money you loaned me to replace the ones I repo’d.

The value of a Treasury security, pretty much like the national debt, is easily calculable down to the penny and easily realized. Those are the characteristics of a low risk market. And they are also the reason why the repo market ends up with a lot of leverage, with all the participants depending on market liquidity not to get steamrollered

Reserve Deposits Are The Life Blood of Repo

In addition to trust, the repo market depends on an adequate supply of reserve deposits. Reserve deposits circulate through the financial system via banks, which use them to facilitate the sending and receiving of payments. If a bank does not have enough reserves to make a payment, it has to either borrow reserves from another bank, the FHLBs, from the Fed’s daily overdraft window, or from its discount window.

Only banks have accounts at the Fed to hold reserve deposits, so all payment flows, including repo settlement, ultimately depend on banks and their willingness to transfer reserves among themselves. If the flow of reserves in the payment market stops because a bank in the circuit holds up a payment, like flight delays, its single delay will cascade throughout the payment system. Therefore, having sufficient reserves and maintaining trust in the system so that banks can freely send and receive is key to financial stability.

Reserve deposits are the difference between the sum of the Fed’s assets and its liabilities other than reserves. The Fed’s “equity” account equaled $45 billion. Its assets are mostly Treasury and Agency MBS securities, plus the temporary balances its discount window loans and in its Standing Repo Facility (SRP), which recently popped up from $0 to as high as $29 billion at month-end.

There is usually some pressure around quarter-end in the repo market because dealers might be managing their balance sheet for window-dressing purposes and tightening liquidity. Still, up until recently, the level of reserves in the system has been so abundant, as the Fed would call them, that dealers have not needed overnight financing, especially when it is not quarter-end. That is, until recently, as shown in the graph in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Standing Repo Facility ($ Billions)

The Fed’s liabilities include $2.4 trillion of currency in circulation, mostly denominated in $100 bills, but also including the $2.5 billion worth of pennies circulating, including those lost and forgotten in mason jars, desk drawers, charity boxes, and landfills. Its other major liabilities are the TGA and the reverse repo facility (RRP).

Importantly, for our terminology-minded readers, my repo is your reverse repo, unless you are the Fed, in which case my repo, when I receive funds that I pay back at the end of the repo and send collateral that the Fed will return, is also the Fed’s repo. Similarly, my reverse repo is also the Fed’s reverse repo, even though for any other counterparty it would be their repo. Got all that?

When the Mint coins more pennies or prints paper money, or the reverse repo or TGA increase, reserve deposits decrease, unless the Fed’s Treasury and Agency MBS holdings increase instead. The Fed can also do repos with primary dealers and other approved market participants to temporarily add reserves, including its SRF, and it can lend money through the discount window. The Bank Term Funding Facility (BTFP) expired last year, but it was another means for the Fed to add reserves temporarily.

On the liability side of its balance sheet, the Fed has no direct control over the supply of currency in circulation. Bank treasurers place their orders for cash and coins they need from the Fed to replenish their teller cash drawers, and the Fed instructs the Mint to get printing and coining. Every new coin or piece of paper money that enters circulation reduces reserve deposits. The Fed also cannot control how much money the Treasury keeps in its checking account — the TGA — which is now over $940 billion, compared to $660 billion at the beginning of September. The increase in the TGA caused reserves to fall by almost the same amount, to $2.8 trillion this month.

QT Is Irrelevant

The only other factor influencing the balance of reserves is QT, which the Fed announced last month it would discontinue in December. However, despite the media and analyst focus on the Fed’s efforts to reduce its balance, the main objective was to reduce the supply of reserves, which it had described as abundant but are now merely ample. But over the 41 months since it began shrinking its balance sheet, reserves up until September stayed flat at over $3 trillion.

Its total assets fell by over $2 trillion, but reserves were unchanged. Since the beginning of September, the TGA increased by $280 billion and the balance of reserves fell to $2.8 trillion. QT only shaved off $35 billion from its balance sheet. And that $35 billion was partially offset by $6 billion from negative Treasury remittances, because the Fed is still paying out more interest to the banks than it earns on its bond portfolio.

Around and Round Reserves Go

Reserves circulate through the financial system and support the repo market. The Treasury’s TGA account increases when it sells Treasurys to the public and collects taxes and other fees from the public. Conversely, when it pays back principal to the public on maturing Treasuries, pays out Social Security and other benefits, and as came starkly into view in the last two months, when it send paychecks to Federal workers including the TSA and flight controllers, the military, food stamp recipients, and government contractors, its TGA account balance goes down.

It is the same as what happens in your personal checking account. The balance falls when you make payments and increases when you get paid. During a shutdown, the Treasury was able to collect money from bond sales and taxes, and pay out maturing principal and Social Security benefits. However, it could not pay Federal workers, food assistance, or contractors, which left money to accumulate in its TGA.

When the public buys Treasurys in the auction and pays taxes, one of the main ways it remits payment is by withdrawals from its deposit accounts held at banks. As the public withdraws deposits to send to the Treasury, banks immediately withdraw reserves from their accounts at the Fed, which reduces the reserves in the system. Similarly, when a Treasury security held by the public matures, the repayment with interest is simultaneously credited to the public’s deposit account at banks. The banks, in turn, deposit the money in their reserve account at the Fed, which increases reserves in the system.

Bumpy Ride from Abundant to Merely Ample

The theory today is that if reserves are sufficiently large, or ample in central bank jargon, then slight changes in the level of reserves should not cause any significant stress in the financial system. The Fed refers to it as reserve demand elasticity, which measures the change in the price of reserves—the Fed funds rate—for a given unit change in the level of reserves. When reserves are abundant, even the swing in reserves from the build-up of the TGA should not be causing what we see today, where repo traders are reporting spikes in the general collateral rate for repo above the Fed’s rate for doing an RRP, taking cash from the public, and sending collateral.

Because today it is safe for Fed officials to say that reserves are no longer abundant, they are merely ample, bordering perhaps on the penumbra of scarce. However, there are not enough pennies for them to tell you precisely how to draw a line. Fed officials say today that they are confident reserves are still ample, but that they may reach a point in the future where asset purchases will be needed to maintain reserves at an ample level.

Bank treasurers remember what happened on September 15, 2019, when SOFR blew out by 300 basis points, spiking from 2.25% at the top of the Fed’s band for fed funds at the time to 5.25%. The Fed had just suspended QT that summer, and the balance of reserve deposits on its balance sheet equaled $1.4 trillion, down from $2.4 trillion when it began QT 1 in October 2017.

The Fed had no intention of returning reserve levels to where they were before the GFC, when reserves were scarce and equalled $10 billion. Back then, its balance sheet did not even equal $1 trillion. However, with $1.4 trillion in reserve deposits at the time in the system, the Fed believed they were sufficient to maintain market stability.

But reserves were not as ample as they thought, especially when tax payments and Treasury auction settlements all converged into one giant drain of reserves from the system. As Lorrie Logan explained, who today is president of the Dallas Fed, but in October 2019 was still working as an official at the New York Fed managing the Fed’s SOMA portfolio,

“In mid-September, upward pressure emerged in funding markets as corporate tax payments and the settlement of Treasury securities increased demand for securities financing and sharply reduced reserves in the system. Consistent with the directive from the FOMC, the Desk responded with temporary open market operations to foster conditions that would maintain the federal funds rate within the target range.”

And today, Fed officials are again confident that they can manage a transition from abundant to ample reserves, even though, if it were not for the change in the TGA, reserves they described as abundant 41 months ago would be unchanged. Indeed, as the government reopens, the TGA will fall and replenish the balance of reserves to where they were before September. In the meantime, they are counting on the SRF to meet temporary needs. But Lorrie Logan said it then, and her words remain as relevant today as they were then. The reality is that the Fed cannot compute reserves down to the penny. And sometimes, being short a penny can matter in a pinch. As she continued,

“It’s worth noting that the quantity of reserves needed to maintain an ample reserves framework is subject to uncertainty and may change over time. Banks’ demand for reserves is not static. It shifts in response to changing financial conditions and will evolve through time as banks adjust their business models and respond to changes in the economic and regulatory environment. In addition, the level of reserves needed to maintain an ample reserves regime is more than the sum of individual banks’ reserves demand, particularly when there are frictions that result in inefficient redistribution of reserves.”

Yes, frictions. Frictions are pennies; they are not just rounding errors, and they add up to something. Frictions can be informational, when I know something you do not, and you have to keep guessing, or when rumors and misinformation lead to financial panics. Certainty and exactitude are beneficial in such situations. When there are plenty of pennies in the world, but you happen not to have enough for exact change, that is a friction, just as when the balance of reserves before last September was holding unchanged above $3.1 trillion, but the Fed still had to address turbulence in the repo market from time to time through the SRF and BTFP.

And central banking is not an exact science, so the Fed will always want to err on the side of caution and not define ample reserves down to the penny. It will be more, you will know it when you see it. Currently, based on the frictions it is experiencing, it believes it may have already crossed a line from abundant to ample, even though the TGA is likely to fall significantly in the next couple of months and push reserve deposits back to their levels when the Fed initiated QT in June 2022. The Fed’s decision to end QT next month reflects ignores that likelihood. As John Williams, president of the New York Fed, said this month,

“This decision was based on clear market-based signs that we had met the test of reserves being somewhat above ample. In particular, repo rates have increased relative to administered rates and have exhibited more volatility on certain days. Accordingly, we have been seeing more frequent use of the SRF. And the effective Federal funds rate has increased somewhat relative to the IORB after years of that spread being at a stable level. These developments were expected as the supply of reserves closed in on ample.”

Circulation Issues

Unlike reserve deposits, pennies are not liquid, much like the cash sitting in bank vaults. However, the penny ecosystem operates much the same way as reserves. The Mint produces pennies and ships them by truck to the 12 Federal Reserve banks, including those in Philadelphia and Kansas City. The reserve banks load them into their own trucks and drive them over to banks that distribute them in their branches, who then distribute them to merchants who still need to make change every day for the 14% of the population that uses it regularly.

The public takes the change home and is supposed to bring the pennies back to the merchant the next day to buy milk with exact change. But that never happens. Instead, the public separates the pennies, and probably also the nickels and dimes, from the quarters because you still need quarters for the parking meter. But even that use will disappear over the next few years when e-payments for the meters become the norm.

Which is the nub of the circulation and economic problem with pennies. When Covid hit, the Mint had a coinage capacity problem on its hands. Because no one wanted to touch pennies or any kind of physical money that someone else touched, and giving away disposable pens at the doctor’s office was a thing, too. Merchants still gave out clean pennies for change, but never took back pennies when the public returned the next day to buy something with exact change. The public wanted more pennies and could not understand why, if they left all their change in mason jars at home, they did not have spare change when they needed it.

Bank treasurers thought it was all about panic and shortages in reserves. Oh, no, bigger problems were going on. And it happened before Covid. Many times in fact. Louise L. Roseman, Director of the Division of Reserve Bank Operations and Payment Systems, described what happened in 1999, during her testimony before the Subcommittee on Domestic and International Monetary Policy of the Committee on Banking and Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, back on March 28, 2000,

“During 1999, the Federal Reserve experienced exceptional demand for all denominations of coins. In several regions, the demand for pennies, and later in the year, for other denominations, at times exceeded the Federal Reserve's ability to meet orders. The average number of coins flowing out of Reserve Banks during 1999 (minus coins flowing into Reserve Banks) was nearly 30 percent higher than in 1998. That number, in turn, was 27 percent higher than in 1997.”

Pennies are in a class by themselves, she continued,

“Coin circulates much differently than currency. This is especially true for pennies, which do not circulate with the same frequency as other coin denominations. The Mint and Federal Reserve have experienced other periods in the 1980s and 1990s when the demand for pennies exceeded the Reserve Bank inventories and the Mint's production capacity. The location of the coin, not the amount of coin, is quite often the problem. People tend to accumulate coins in desk drawers, jars, or on the tops of dressers.”

Penny Dreadful: Lost Seigniorage

Pennies do not have a lot going for them. People use them sometimes, but it is more from a necessary evil perspective, because they don't want to pull out a credit card for a one-penny item, and they just happen to have the penny in their pocket. Pennies are a bother. Nobody seems to be losing much sleep knowing they will wake up one morning and all the pennies have gone. However, pennies are also an economic loser for the U.S. Mint, and the truth is that minting money in a capitalistic system like ours is about generating revenue.

It is called "seigniorage," which, as the Bank of Canada explained in a 2022 note, refers to the practice of minting money at a cost that is less than the value of the money produced. The U.S. Mint, like any business, generates revenues and incurs a cost of goods sold. Take the numbers for 2024. It coined 3.2 billion pennies, which was worth $32 million. Each of the copper-alloyed zinc blanks used to make the coins, plus the electricity and maintenance costs to run the minting machinery, makes each coin cost approximately 3 cents to produce.

But there is more to the numbers than just the cost of goods sold. You have selling, general, and administrative (SGA) expenses, which tack on another 0.66 cents. Finally, you have distribution costs to pay for the gas needed for trucks to haul them to the Federal Reserve banks, for 0.03 cents, leaving the total unit cost equal to 3.69 cents in 2024. In dollar terms, last year the Mint lost $86 million and some change on seigniorage, making pennies that no one wants, except for charity boxes that would gladly accept donations rounded up to the nearest nickel.

Numbers like these are terrible, but even worse when you compare them to expenses from prior years. In 2023, the cost of goods sold was 2.72 cents per coin, and the year before that it was 2.43 cents. And someone at the Mint must be getting a bonus because SG&A expenses went from 0.26 cents in 2022 to 0.33 cents in 2023, before doubling to 0.66 cents in 2024. A decade ago, the Mint was estimating its cost of goods sold as a third of that. (See the first five slides in the chart deck this month for more details.)

But if you think pennies are upside down on seigniorage, wait until you look at the costs for nickels, which might be worth more than plug nickels but still not enough to be economical. It cost the Mint 13.78 cents to make one nickel worth 5 cents. Fortunately, it only made 202 million nickels in 2024, so the Mint only lost $17.7 million making them. Compared to the dime and the quarter, which combined to generate $201 million in seigniorage last year, pennies and nickels collectively cost taxpayers $103 million. Pennies definitely needed to go, but if you are a nickel these days, it's best to hide in the closet.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2025, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief

This Month’s Chart Deck

This month, the Treasurer of the United States, Brandon Beach, pushed the last copper-alloyed zinc blank coin through the U.S. Mint’s coining machine and made the last penny. After 232 years, the U.S. Mint will no longer produce pennies, leaving the public with just nickels, dimes, and quarters (plus the occasional and rare half-dollar) with which to make change. In 2024, the Mint added 1.3 billion pennies into circulation, far exceeding the production totals for the other coins it makes (Slide 1). The truth is that the Mint spent 3.69 cents last year to produce pennies, and production costs doubled over the last decade, especially since Covid (Slide 2). The penny’s unprofitability is dragging down the seigniorage profits it makes from its entire coin production line (Slide 3).

Part of the reason the coin is so unprofitable is that, due to the increasing use of non-cash payment alternatives, the public does not return coins, especially pennies, back into circulation. The Mint continues to produce them, but the public often stores them away or even discards them (Slide 4). Even if it does not throw them out, the coins it does save are not worth its bother to deposit in banks or use for payments (Slide 5) in retail transactions.

Bank supervisors proposed easing capital requirements on large global banks subject to the enhanced Supplementary Leverage Ratio, which the industry complains is a binding constraint preventing them from investing in more Treasuries. But Slide 6 suggests that capital constraints may not be the only factor holding large banks back from buying more Treasurys, which already represent 8% of the balance sheet for all commercial banks. It probably also does not help the industry’s appetite to buy more bonds when existing bond portfolios are still underwater (Slide 7).

The Fed is paying close attention to the volatility in the Treasury repo market, which officials believe is a sign of stress in short-term liquidity that may be related to Quantitative Tightening (QT), which the Fed plans to suspend next month. For example, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) has been highly volatile lately when compared to the rate the Fed sets for awards under its Reverse Repo Facility (RRF) (Slide 8), where it borrows cash and sends collateral to money market funds. Fails to deliver and receive are also up among primary dealers as a sign of stress (Slide 9). However, the bar graph in Slide 10 presents clear proof that the drop in the balance of reserve deposits, which directly correlates with a stable trading market for Treasurys, is almost entirely due to the increase in the Treasury General Account (TGA) balance because of the shutdown and not because QT is reducing reserves in the system.

Losing Money Making Pennies And Nickels

Penny Production Costs Skyrocketed Last Year

Pennies and Nickels Are A Drag On Seigniorage

The Dirty Truth No One Admits

Remembering Piggy

Banks Have Limited Capacity For More Treasurys

Bond Holdings: Still Digging Out

Repo Stress Increasing

Delivery Fails Elevated

Shutdown Leaves TGA Up, Reserves Down