BANK TREASURERS IN THE AGE OF AI

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) voted to reduce the range for the Fed funds rate by 25 basis points to 3.50%-3.75%, the lowest level for the overnight rate in three years and 175 basis points below its peak in July 2023 when the range was 5.25%-5.50%. The vote to cut the rate this month masked deep divisions among committee members: Jay Powell and eight others supported a 25-basis-point cut, three opposed, two voted against any cut, and one, Stephen Miran, voted for a 50-basis-point cut. Until the Fed began cutting rates in September 2024, monetary policy decisions were generally unanimous.

The new dot plot published this month reflects these deep divisions at the FOMC, as long-run projections for the mid-point Fed funds rate ranged from 3.875% to 2.375%. But differences among FOMC members concerning monetary policy are not as extreme as those concerning economic projections. Members’ expectations for inflation and unemployment were unchanged primarily since their forecast last September and remained within a narrow range.

No members forecast a recession on their three-year horizon. Government bond traders bid up bonds in secondary trading after Chairman Powell’s press conference, cheered by his comments that recent job gain statistics may overstate the job market’s actual condition, that the FOMC does see evidence that inflation is coming down, and that monetary policy is at the upper end of neutral, suggesting that room for another 25-50 basis point cut in Fed funds next year was not out of the realm of possibility.

The committee also stated its satisfaction that the level of reserve deposits in the banking system met its definition of “ample” and directed its Open Market desk to resume asset purchases in Treasury Bills to maintain reserves at current levels. As this month began, the Fed held Treasury bills totaling $0.2 trillion, compared to the rest of its $3.8 trillion Treasury securities book and $2.1 trillion in Agency mortgage-backed securities. Reserve deposits totaled $2.9 trillion this month, only $0.3 trillion below the level when it began Quantitative Tightening in June 2022, and most of this decline occurred since last September, during the Government shutdown, when the Treasury General Account increased from $0.6 trillion to $0.9 trillion.

Meanwhile, the U.S. banking system holds record levels of loans and deposits, both of which the industry has grown at roughly the same pace since the Fed’s last rate hike in July 2023. With an aggregate industry ratio of loans to deposits of 71%, the industry objectively still has excess deposits that it needs to hold in reserve deposits at the Fed or in bonds. Despite numbers that generally describe a financial system with ample liquidity, frictions appear to put pressure on short-term repo, which appear stressed, with the Secured Overnight Financing Rate consistently trading above the effective Fed funds rate and sometimes through the FOMC’s ceiling.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and related large-language, data-intensive technologies such as machine learning and generative AI are the buzzwords in the bank treasury space this month. Treasurers and thought leaders in banking institutions, large and small, are focused on ways to implement AI projects in 2026 and have high expectations that their efforts will lead to higher growth and improved productivity. Indeed, data-dependent industries have most to gain from the AI technology. AI-related stock prices doubled in the past year and remain at or near record highs. So far, however, shareholders have been frustrated to see returns fall to the bottom line as management plows AI-related efficiency gains into new investments in the technology or into retraining employees in AI-vulnerable positions to take on other, similar-paying positions in their organization. The technology also comes with considerable risks, including costs for data infrastructure and security, and the state of technology is not yet at a level where it can do anything innovative or creative, which remains a future goal.

Part of the challenge that bank treasurers face in integrating AI technology into their departments is identifying effective use cases. Identifying problems AI can solve requires that they lead the way and not defer integration to their IT department or junior staffers. Because only bank treasurers and their senior peers at the bank understand the problems that, until AI, they were unable to solve, and what the technology can and cannot do to connect questions with answers. Use cases today include analyzing loan documents, asset-liability management, liquidity stress testing, cash flow projections, hedge design, and data collection and reporting. Bank examiners are experimenting with ways to incorporate AI into risk monitoring and analysis. Fraud detection remains a leading use case. Bank treasurers are also looking at AI/machine learning software for risk scenario generation, peer analysis, and optimizing the structure of their bond portfolios.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

Submitted for your approval. On March 2, 1962, quite out of the blue (although, back in those days, on television the sky was black and white), an alien spacecraft landed on Earth. The Kanamits, portrayed on the 24th episode of the third season of the 1960s television show, "The Twilight Zone, were a fictional civilization from another planet and another galaxy light-years more advanced than anything human civilization on Earth could have ever imagined then or even now.

They said they came in peace to help the people of Earth overcome their difficulties. Earth was in a bad state, and its people were unhappy. Disease, famine, pollution, and climactic upheaval ravaged its landscape, wars devastated its economies, and death stalked the land. The world was less than a year away from the Cuban Missile Crisis. Man against man was the state of affairs, and uncertainty, insecurity, and desperation were the everyday norm.

From a bank treasury perspective, things seemed okay, at least on the surface. Interest rates were low, with the Fed funds rate just under 3%. Inflation was low, maybe too low at 1%. Unemployment was not fantastic at 5%, reflective of an underperforming economy still climbing out of the 1960 recession, but not awful.

Experts argued over fiscal policy. The deficit hawks argued for budgetary restraint, and the Keynesians wanted a stimulative tax cut. All of this was not too different from today, even if the data from the 1960s might have made more sense, with inflation and unemployment more closely aligned. But disagreements were not publicized. Fed policy officials certainly did not air their disagreements in a “fractious” vote on a rate cut, as they do these days at the FOMC.

Bank treasurers were worried at the time, though not because the financial system was at risk. Not that they ever need a reason to worry. If problems are not manifest, they will worry about what they do not see. From experience, having seen the movie, bank treasurers know all too well how small tails can turn into fat tails with a finger's snap. So, of course, they worried back then.

Because bank treasurers always have to worry about something, even good news is worrisome. The Glass-Steagall Act was still the law of the land in 1962, and the memory of the 1929 Great Crash and the Great Depression it caused still haunted both sides of the political aisle. Partisan thoughts to roll back regulations as unfair and anti-banking, uneconomical and overbearing as ever there were, were the furthest thing from Congressional minds on both sides of the aisle back then.

The law served as a veritable wet blanket over risk-taking. Thus, no banks failed that year, which is why bankers worried that the financial system was not taking enough risk. As Wright Patman, then chair of the House Banking and Currency Committee, said in 1963,

“I think we should have more bank failures. The record of the last several years of almost no bank failures and, finally last year, no bank failure at all, is to me a danger signal that we have gone too far in the direction of bank safety.”

You could almost hear the robot on “Lost in Space” say, “Warning. Danger Will Robinson, danger!” They said they came to serve man and asked to speak with Earth’s leaders. Still, they were not exceptionally verbal, as the Kanamit representative explained, addressing members of the United Nations,

“Our own methods of communication are mental rather than verbal. Hence, the voice you hear me speaking with is totally mechanical. Your words, or rather your thoughts, are fed into an automatic translator and my responses are in turn electronically altered to simulate those vocal sounds and language known to you.”

Like Alexa and Siri, they heard even one’s innermost thoughts, could anticipate wants without you even asking, and, creepy as that sounds, they only wanted to help us. On their planet, there were no wars, and people were well fed, but not so well fed that they needed to jab themselves with GLP-1 to keep their weight down. People settled their differences with words, not fists. Society was inclusive and connected. Everyone respected everyone else, and there were no wants. Energy issues were nonexistent; there was no pollution, waste, or inefficiencies. The Kanamits powered their lives with clean atomic energy, but had no nuclear waste to worry about.

The Kanamit representative went on,

“I hope that the people of Earth will understand and believe when I tell you that our mission upon this planet is simply this - to bring to you the peace and plenty which we ourselves enjoy, which we have in the past brought to other races throughout the galaxy. When your world has no more hunger, no more war, no more needless suffering, that will be our reward!”

They left behind a mysterious book written in their language. “To Serve Man” was what it said on the front cover. At least those few words were as much as the brightest minds, unaided by modern-day large language models, working for months, were able to decipher, under the direction of Michael Chambers, a lead character on the show. Translating the Kanamit language was beyond anything any coder had ever seen, a language so complex that the human mind could not fathom, let alone understand, without millions of hours of work trying to decode and read beyond page one.

While they toiled day and night to decipher the Kanamit language and the book, the world grew increasingly excited that the Kanamits could do as they said and rid it of all its troubles. It was so easy to believe that utopia was just one press away on the F9 key. The people of Earth fought for a place in line to visit the Kanamit planet, where they heard visitors would find an entire world of things they could take for free, quite like open AI and ChatGPT

AI Just Wants to Serve Bank Treasurers, Not Replace Them

But some were suspicious of their intentions, much as concerns today about the promises AI and machine learning technologies offer the world. It could be nothing; the Kanamits could have only wanted to serve man, but something could be sketchy. AI might be wonderful, but it might also be sinister because not everything is as it seems.

Machine learning technology is conquering breast cancer. It can find patterns that no human could detect from seemingly random dots, and AI can detect fraud, find forgeries, prove, and establish identities that were once too obscure to find. It can predict the weather, save time, prevent errors, and take on mental tasks too tedious and taxing for mere human minds.

It can drive cars, cutting down on highway fatalities. Yes, WAYMO robo-taxi were caught passing a stopped school bus. Some of them are starting to act almost human, edging through crosswalks at red lights and making illegal U-turns. Regardless, it can help thedisabled live fuller lives and the abled live enhanced lives. It is always on the job, unlike humans, who need rest occasionally and never need financial incentives to get their work done; it performs flawlessly, even if it hallucinates occasionally and cannot tell time or get or take a joke.

Building Good Ideas Is Not Enough

AI can be the way forward for everyday tasks, much as the dishwasher and vacuum cleaner were when they went on the market. Think of any invention, from radios, television, internet, WiFi, cars, trains, planes, refrigerators, freezers, toaster ovens, coffee makers, and last but not least, cell phones. No, actually, the list goes on and on, an endless list of inventions that were economic and socially transformative. As the president and CEO of a global bank said last October, AI must revolutionize everyday processes,

“When you wash dishes by hand, it’s one process — the dishwasher results in a clean plate, but the way it washes the dish is completely different.”

However, just building it will not get "Them" to come. Inventions take off when the total addressable market — the TAM, as private equity investors like to call it — sees them as solving an immediate problem better than any other solution. They become household products when everyone just needs them and wants them at hand right away. They have to be so fundamental that once people have them, no one can imagine a time when they did not exist.

Those digital LED-illuminated hand calculators that came on the mass market in 1971 were a great idea in search of a problem. Because at first, people who had them loved to go around showing off how it added "2+2" by pressing Enter for "4," which was nifty but not particularly helpful. It did save bank treasurers' time adding up long columns of numbers on a hard copy of the bank general ledger, and some bank treasurers in those days liked to carry their calculators in their shirt pockets, armed and ready to add, subtract, multiply, and divide at a moment’s notice. But no one generally walked through busy streets holding them, as people do with cell phones today, glued to their screens while running through airports or crossing roads in front of moving cars.

And even cell phones went through a “what do we do with this” phase, when people who had one would call others just for the novelty of it. But later on, HP-12C calculators came on the market, and bank treasurers could suddenly do bond math with them. That is when calculators really took off in the banking world, that aha moment. That is when they became a household product, much like cell phones when they became smart.

AI needs to be a household product, a smartphone, and for that to happen, it needs a strong use case, stronger than any known ones to date. AI cannot just be a good idea. There are lots of good ideas, but to be a household product, it needs to solve THE problem. Before iPhones and Samsungs, people used Motorolas and Blackberries and saw no reason why surfing the internet during a meeting was a critical need. Today, who gets through meetings without looking at their smartphones?

AI Use Cases

Not to say that AI isn't already helping humankind, like helping bank treasurers detect fraud, track cash flows, and improve the efficiency of customer service delivery. Bank treasurers are even starting to use it to design hedging programs. The key to success with these efforts is when bank treasurers themselves lead by example using the technology, as this KPMG study concluded. Pilot programs do not work when they are handed off to an intern to figure out.

What bank treasurer today isn't thinking hard about liquidity planning? AI can help with that, and the return on investment is high. Think about it this way. Holding cash used to be a no-brainer a couple of years ago, when the Fed's overnight rate for reserves was at its highest point on the yield curve. But the Fed just cut rates again, and holding cash no longer pays as well as it did. On the other hand, instant payments are changing the way cash flows on and off the balance sheet, making liquidity planning both critically essential and much more complex than before. AI can put all that together.

AI technology can analyze historical data, incorporate internal data alongside macro data, market, and economic trends, enabling bank treasurers to make instant, more accurate decisions about liquidity planning than ever before. And the real payoff is that they may not need to hold as much cash as they think, and can instead invest in more profitable loans or the bond portfolio, and generate more net interest income growth and net interest margin. At least that could be in theory, when AI becomes a household item. Right now, it is not.

It could serve as a bank treasurer's co-pilot, a side-kick even if it cannot do jokes well. Think about how hard it is to design and execute a hedging program with the market moving everywhere all at once. You've got news feed to think about, live market data, and a lot of uncertainty to figure out while executing a complex delta hedge using one of those accounting-friendly interest rate swap SOFR futures contracts Eris Innovations created.

AI can ingest tons of raw data, analyze it, spot trends, and find optimal hedging solutions instantly. Bank treasurers can hit the bid and lift the offer with confidence and good timing. All a bank treasurer needs to do is execute the trade, and even that could be automated if wanted. AI is just here to serve bank treasurers, not replace them.

AI Transformations Begin With Questions

But AI is still in a calculator phase despite its promise. To go beyond a pilot project, AI needs broader take-up. Successful innovations reach a point where demand inflects. Demand inflects when people reimagine processes, when washing dishes by hand no longer seems quaint but downright unsanitary. The president and CEO of the global bank asked the question that bank treasurers need to ask themselves,

“How do we get our teams to look at a process end to end and completely re-imagine how they’ve done it manually in the past to now?”

How? It starts with a good question. In the novel, "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy," a supercomputer named Deep Thought took 7.5 million years to work through the answer to the meaning of life, and after all that time, it revealed that it was the number "42." Unfortunately, the data scientists who built the computer had no idea what the ultimate question it solved was, so its answer was meaningless.

AI is like an expensive exercise bike that, unused for its intended purpose, becomes a coat rack. To make AI popular, managers need to get their people to use it to do the most odious, awful chore a bank treasurer can imagine. As the above-quoted bank executive went on to say, let the bank treasurer use it to fill out a performance appraisal,

“There are ways to make it popular with your organization by eliminating some of the greatly dreaded annual processes you have. I think I heard the cheer around our firm globally when we told everybody that they would be able to do the performance reviews — the AI tool we have will do the first draft of them.”

Well, there you go. What manager would want to do something so fundamental as to tell an employee that they were terrible at their job while sounding constructive and picking out the things they were good at when there is not much to say? A few key strokes in ChatGPT would get that chore done in seconds. But managers are advised to still check over its work.

Our corporate sponsor friends at ORSNN, a whole-loan electronic trading platform, use AI much like transcription services that turn audio files into written documents in minutes, but even more advanced than that. ORSNN’s AI lets buyers and sellers on its platform upload loan documents in minutes to create a visual representation of the loan on a computer screen. As bank treasurers know, going through a whole loan file the old-fashioned way is not fun. It is a real chore. There are details, there are mistakes, and sometimes the information is not presented in a uniform structure.

That is why they usually have their college intern working on the trading desk do it, and then wait at least a week for the poor kid to complete the analysis and prepare the file for trading. Using ORSNN to buy or sell whole loans gets customers to use AI to solve problems as a matter of course.

The World Bank also uses an AI application like ORSNN's to help facilitate cross-border payments. It calls its application SHASTRA, meaning "Shaping Capital Markets by Enabling a Single Source of Truth for All." SHASTRA pulls out trade terms from dealer term sheets for funding and asset-liability management (ALM) transactions.

AI can be a game-changer in scenario risk modeling, which is a super tedious process. Straterix, a risk-modeling and scenario-projection software company, uses machine learning to project a bank's financial data across thousands of potential scenarios and calculate the potential that a bank's financial performance deteriorates, stays the same, or improves over a set horizon in mere seconds. The Straterix technology works through the permutations for each scenario: if A happens, then B, or then C, and then if D, or E, or F, and shows all of its work, fully transparent.

In fact, it can tell bank treasurers the probability distributions of those outcomes using only publicly available call reports, without looking at any proprietary data. And bank treasurers do not have to worry that they will not be able to explain how machine learning can do this, what the heck does stochastic regression mean, any more than they need to worry about how to explain to their examiners how their HP-12C app on their cell phones works. Every calculation is transparent. All bank treasurers need to know is that the calculations the software produces in seconds would take an intern and a roomful of other interns eons to complete.

Finding patterns and crunching out endless permutations is what machine learning does better, infinitely better, than what a human mind can ever hope to do. Machine learning, in this case, does not replace an intern, but it can make that intern infinitely more productive when using it. But how productive is an open debate.

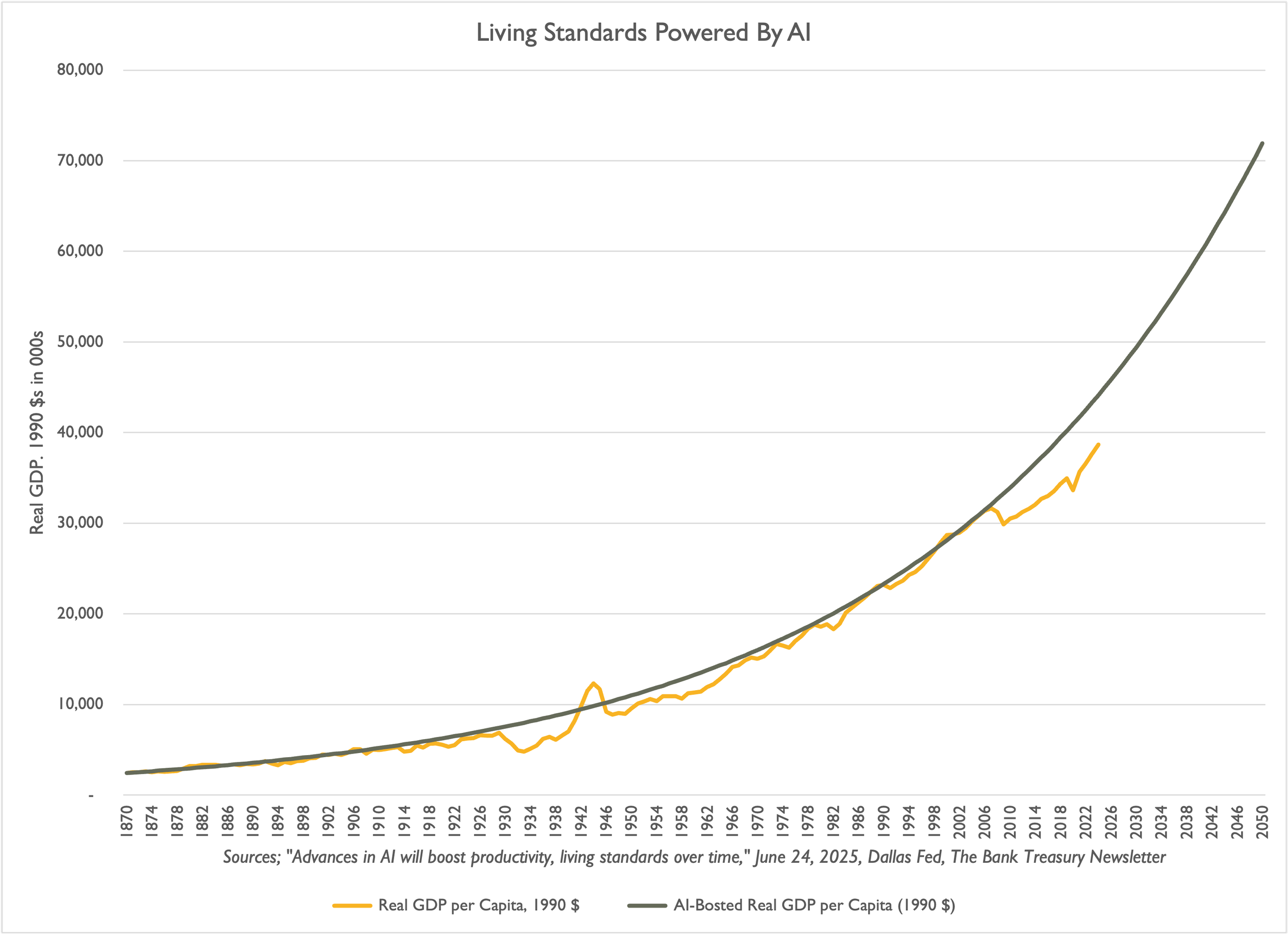

According to a recent Fed study, there are two types of inventions. There are inventions that increase productivity temporarily until the market is saturated with them and then economic trends settle down, like the lightbulb or diswasher. Then there are inventions which transform growth by unlocking future inventions, like an electron microscope or even a smart phone, that lead to sustained higher economic growth, or at least, more informed opinions around a dinner table.

Successful integration of AI technology in bank treasury begins with good questions. A study published last October by Citigroup listed many critical questions that treasurers need to ask and get answered to use AI and get value from it,

“Which tools are appropriate? Is our data sufficient? What approvals are required? Where can we find the right resources? How can we validate GenAI outputs? How do we measure the benefits? Can we explain the results?”

AI’s Promising Economics

On the other hand, these new technologies are not without their risks. If managers are using ChatGPT to write performance appraisals today, if interns can save so much time dissecting loan documents with AI, and if risk managers using machine learning do not have to resort to the seat of their pants to estimate the probability that their institution might run into trouble tomorrow, maybe tomorrow their employers might not need as many managers, interns, or risk analysts, or perhaps not need them at all.

Sure, humans cannot be replaced today, at least that is what everyone is saying. As the chairman and CEO of another U.S.-based global bank said in an interview last month,

“You can’t replace human capital. You can’t replace thinking. All these things that people think are going to happen won't happen exactly the way you’d expect.”

AI is not yet at the stage where humans can trust it with large decisions, like a large loan to a large important customer, as the CEO of an overseas global bank explained,

“Then there are very large decisions, which require the more fundamental issues of client selection. I think that’s going to be human for a while yet.”

There is a very good reason why AI will never replace people. You cannot have a relationship with it, according to the CEO of U.S.-chartered global bank.

“You can’t teach relationship-building, trust, advice-giving.”

He might want to reconsider what he holds as an article of faith, as news articles document people forming attachments to chatbots. Chatbots are entering religious institutions, and today, some people even prefer an AI cleric to a human one. Forming attachments to AI is no joking matter. In some cases, the attachment led to a fatal outcome.

Even if AI does not eliminate jobs wholesale, as the car did to horse-and-buggy drivers a hundred years ago, jobs will still be lost. It is inevitable, as Fed Governor Michael Barr conceded in a speech last month,

“AI has led firms to scale back hiring, a development that may be contributing to the recent low levels of job creation in the U.S. economy, a concern for many workers and particularly for newer entrants to the job market.”

Fed Vice-chair Philip Jefferson recognized AI’s promise, but echoed Fed Governor Barr’s concerns,

“AI can enable a worker to complete in seconds or a few minutes tasks that previously took many minutes, if not hours. Already, it is boosting worker productivity…Increased productivity leads to economic growth, which may also create new employment opportunities…At the same time, many people have legitimate concerns that AI will cause job loss. At least for certain firms and workers in certain occupations, this is likely to be true. Indeed, some large employers have recently indicated they are lowering overall hiring plans in light of advances in AI…Some research has also suggested that AI is having a more detrimental effect on the job prospects of younger, less-experienced workers, including recent graduates….”

Bank management recognizes the risks but is focused on the upside, as the president and CEO of a global bank insisted,

“I don’t really want to say to people, ‘I can see this taking our overall headcount down’…If AI results in 10% or 15% efficiency gains, you can reinvest that to grow faster, or you take it to the bottom line.”

AI Drives Efficiences in the Economy, and Some Workers Out of It

AI is about efficiencies, even if it also means fewer jobs. The CEO and president of another global bank were not afraid to say the quiet part outside. AI will lead to job losses, he said, except that it may hurt some departments (think customer service) in a bank more than other departments (treasury, for example),

“The AI conversation is an…opportunity to drive, significant increases in efficiency. What it's going to do to headcount…and anyone who doesn't say that is just either, doesn't know what they're talking about. Most people do, but they're afraid to say it because no one wants to stand up and say that, we should have, that we're going to have lower headcount in the future. It's a difficult thing to say. Now it doesn't mean that it's going to happen next year, and it doesn't mean that it's going to happen in every area of the company.”

The point is not about reducing headcount, he went on to say. It is about making the process more efficient,

“We've rolled out these Gen AI tools within our engineering workforce. We're 30 to 35% more efficient in terms of writing code today. We've not reduced the number of people we have coding today, but we're getting a lot more done, that's real efficiency…It doesn't matter whether it's compliance, whether it's legal, whether it's call centers, whether it's pitchbooks in investment banking, credit memos in the commercial bank, these are all opportunities to do things much more efficiently with AI, than humans have been doing. Now it's not going to totally replace humans, but it does create an opportunity to do things significantly different.”

Bank executives insist that rolling out AI will mean that they will do everything to retrain displaced workers and avoid disruptive lay-offs, as he finished saying,

“We're going to be very careful about doing things in a way that are very responsible. We're trying to be very thoughtful about what it means for retraining workforces, use attrition as our friend.”

The chairman and CEO of a major global bank said the same. Using AI does not excuse being careful and having common sense,

“You shouldn’t do it if you're going to put two million people out of jobs. The way to handle that is retraining, income assistance, slow it down, early retirement, relocation programs, and it’s all doable. And that would have to take both government and business doing that together.”

But the truth about retraining workers is more nuanced, as a New York Fed study found. A customer service representative replaced by a machine could indeed train to use AI and move into a higher-paying job. The New York Fed study estimated 25%-40% of so-called AI-exposed workers could get retrained and earn more money. But a lot depends on conditions in the labor market, and the authors cautioned that they based their findings on an analysis of worker salaries after Covid, when companies had to pay up for skilled workers, which is less the case today.

The Fed’s latest Beige Book report underlined the strength that skilled workers who can use AI enjoy in the bank treasury job market.

“Demand for workers largely remained subdued, with labor supply continuing to outpace labor demand. Still, demand for workers in finance and technology, especially those with AI skills, remained extremely strong, with firms having difficulty filling such positions. A contact in upstate New York's tech sector reported that attracting and retaining these highly skilled professionals had become increasingly difficult, citing competition from larger industry players that have been able to offer more lucrative compensation packages.”

AI is going to make bank staff more productive and worth higher salaries, as AI-enhanced sales staff will be able to take client prospecting to a new level, as the chairman and CEO of a large banking organization based in the Southeast told analysts at an industry conference this month,

“We've created tools and capability using technology, using AI to help rationalize and prioritize client prospecting.”

And it is not all about efficiency, he went on to say.

“I view AI as the propellant…It's not a separate thing. It's not a different thing. We don't stop and say, hey, let's do some AI. AI is the propellant. It's the powered by in terms of the things that we're trying to accomplish…I think it's too easy to just say, oh, it's an efficiency play.”

The chairman and CEO of another large domestic bank headquartered on the East coast would not call AI an accellerant, but rather a propellant to cut headcount,

“AI will definitely be an accelerant in our tech headcount, as we are already using it in the programmer role.”

Investment in AI technology will lead to headcount reductions, but returns on investment, which fall to the bottom line, remain another matter. The chairman and CEO of a large regional bank based in the West cut his headcount, but then reinvested the savings into more technology spending,

“We're down…full-time equivalent employees…I think we've got things going on with AI that will be productive. But at the same time, we've been very much in investment mode with systems over the last decade…We'll keep investing in technology. That's just going to be always a constant.”

AI Singularity

When do shareholders finally see returns on investment in AI materially improve performance, move beyond promise to reality? According to the chairman and CEO of a large Northeastern-based institution, banks reach that point when technology transforms the process, and managers reimagine how the bank operates. AI cannot answer that question for them, but AI can be the tool to help them,

“You're at a point in time where with the kind of innovation that we're seeing in technology in AI, gen AI, large language models becoming more sophisticated -- there's opportunities to just say, hey, in three to five years, like how do we want our call centers to be interacting with our customers? How do we want the fraud process to work? How do we want to be onboarding our customers? How much self-service can we offer to our customers, and they can solve their problems without handoffs from one department to the next.”

A Rand study this year identified five stages in the evolution of AI. First, it learns a language to communicate with humans and starts performing basic tasks. Then, as technology advances, it begins to perform basic reasoning and problem-solving at a high school level. Then it progresses enough that bank treasurers start relying on it and stop checking its work all the time. AI becomes autonomous for routine stuff, but all the creative fun stuff stays with the human treasurer and staff, who are getting older because no interns get hired anymore to work and learn.

The banking industry’s take-up with AI is somewhere between stages 2 and 3. In the next stage, AI becomes more innovative and creative, which is when bosses reach a point where they can switch to a cyber-staff. The final stage is when a machine, even the CEO, runs the entire company. Scientists call this stage the AI singularity stage, the stage when AI achieves artificial general intelligence (AGI).

Andrés Pazos, a Country Manager at Amazon Alexa in Spain, spoke at a recent industry conference, believed that singularity is still far off,

“Right now, we’re still in narrow AI—algorithms performing specialized tasks. The next step is AGI: systems that can outperform most humans across a wide range of tasks. Beyond that is artificial superintelligence—AI that surpasses human capability altogether. That’s still more science fiction for now.”

One day, the next Fed chair will not come down to Kevin Hassett or Kevin Warsh, but maybe to a humble machine named IRA, short for Interest Rate Analyst. The Fed could just run an AI program that decides whether, after this month's rate cut, 2026 should be a year to cut fast or cut slow. The tech isn't there yet for that, but AI is nonetheless central to central banks. The wizards who designed it had central bank economists in mind.

A BIS study published last October found that central banks are already using AI to help with policymaking. Fed staff work with vast data sets and complex decision-making processes, viewing it as boosting efficiency and improving policymaking effectiveness. Central banks have more work to do on data governance, human capital investment, and information technology infrastructure. But AI is already transforming the way they run payment systems, collect and analyze data, and supervise banks. They are still mostly in an experimental phase, but in supervision, for example, regulators are using it for tasks such as financial risk assessment, governance assessment, and regulatory reporting.

Regardless of how advanced the technology becomes, AI will never be better than its data, and data security and integrity are key issues the BIS consistently flags. Data infrastructure, reliability, and accuracy are the central focus of BCBS 239. Straterix’s machine learning software, for example, needs at least 30 data points to generate reliable results. But call report line items change from quarter to quarter, which require calculations to make adjustments for those changes and data breaks. Sometimes adjustments to fit the data to outliers lead to risks of their own, as a Brookings study found.

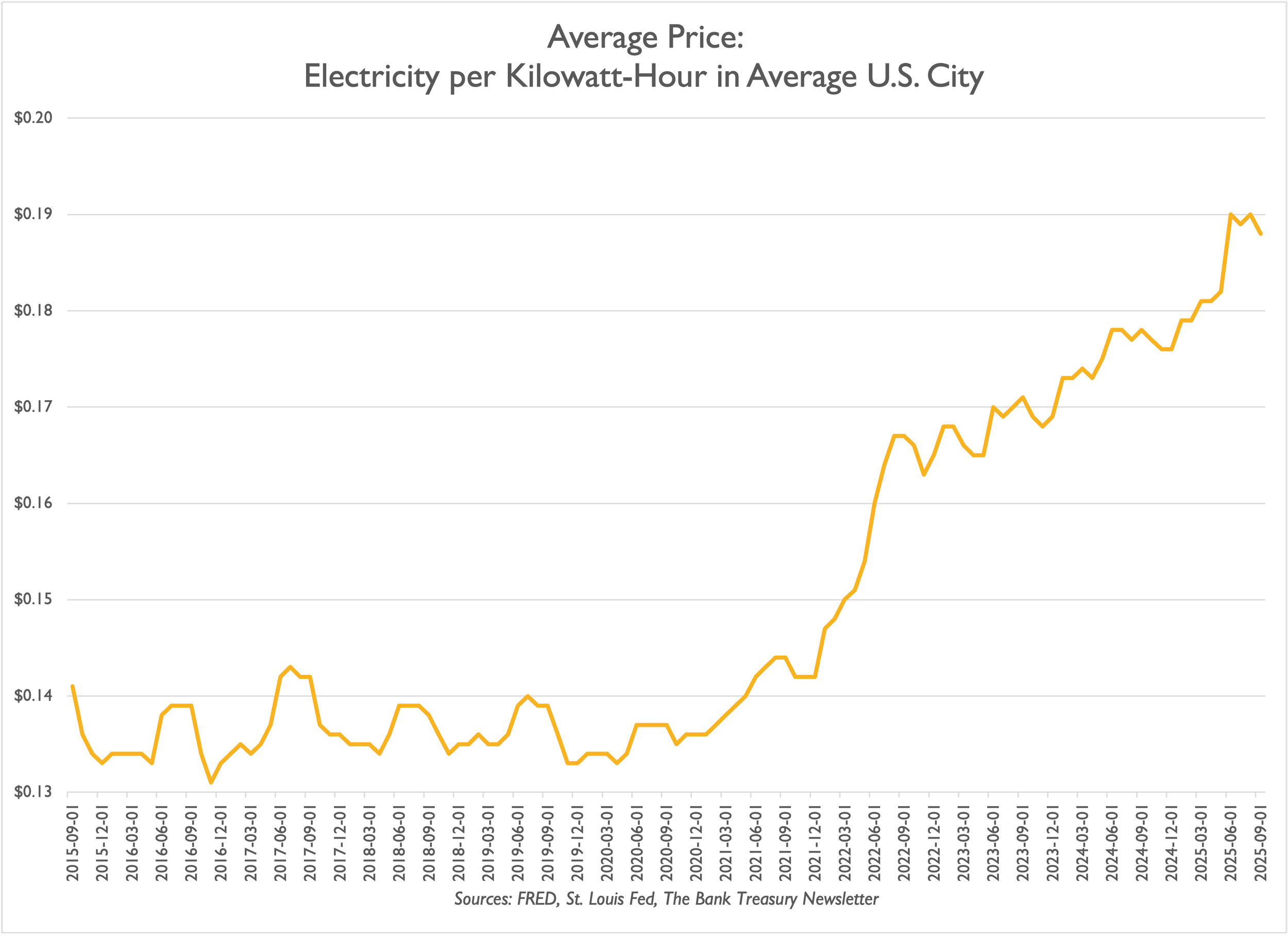

Companies find they pay the price when they do not pay sufficient attention to ensure data security. They also need to worry about whether they have enough capacity to run large data sets and balance power needs with the return on their use. Consequently, data center design and construction businesses are booming. Google, Amazon, Apple, and Meta reportedly will spend $400 billion next year on data centers on top of the $350 billion they paid this year.

Beyond data security and job losses, according to IBM research, there are many other reasons that bank treasurers who are looking for ways to incorporate AI and machine learning into their work lie awake at night. AI raises bias risks; it heightens vulnerability to cybersecurity attacks, you have to worry about data privacy, its environmental harms, the potential for intellectual property infringement, and misinformation. Using AI for insurance underwriting, for example, can reduce an insurer’s costs, but it also could cost it customers, turned off by the fact that a machine was deciding whether or not to approve a claim.

No one wants to talk to machines, no matter how smart they are supposed to sound. Machines do not care about a human’s issues, such as the need for life-saving treatments that are unlikely to help. A Pew poll published last September found that 53% of Americans believe that AI will erode their creativity. However, they disagreed on whether it would help or hinder their ability to form meaningful human relationships. A minority thought it would help them make difficult decisions.

The reason AI will probably never be trusted to make hard decisions may have nothing to do with its capabilities. Maybe we could replace the FOMC with AI. Maybe CFOs and bank treasurers will be more machine than human in a few years, but blaming a machine for bad decisions is nowhere near as satisfying as blaming a fellow human being. Anyone who has ever had the frustration of yelling at an AI bot customer service rep after getting picked up and put on hold multiple times while pleading to talk to a human being will know precisely why humans can never be out of the picture entirely when AI takes over the world.

Some data scientists are warning the public about AI’s existential threat to humankind. Because what happens if AI develops consciousness and, like Hal 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey, calmly concludes that man is the enemy. They can still hear it tell Dave, the astronaut, that it tried to kill when it locked him out of the spacecraft and would not let him back in. “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.” An open letter written in March 2023 by the Future of Life Institute explained why this worry may not be science fiction,

“Contemporary AI systems are now becoming human-competitive at general tasks, and we must ask ourselves: Should we let machines flood our information channels with propaganda and untruth? Should we automate away all the jobs, including the fulfilling ones? Should we develop nonhuman minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete and replace us?”

Maybe your editor-in-chief watches too many science fiction movies and television. But what if? For example, AI this year passed the Turing Test. Alan Turing designed the test in 1950. It says that a machine can think like a human if it could fool a human reviewer of its written responses to interactive questions. Well, guess what, AI crossed that line in the sand this year.

AI might already be a superintelligence by next month, according to some experts. But some self-serving tech entrepreneurs believe that AGI could come by the end of the decade if an extreme asteroid tail risk strike does not take our world out beforehand, or, considering that AI stocks grew in value to new heights this year (Figure 1), the eventual bursting of the AI stock bubble does not devastate the financial system instead.

Figure 1: NASDAQ Global AI and Big Data Index

Should bank treasurers fear AI? The CEO of a large global bank welcomed the technology, despite all the fears. AI is going to make our lives great.

“I would say embrace it. Technology has downsides—it’s used by bad people—but embrace it…Employees in the developed world will be working 3.5 days a week in the next few decades and will have wonderful lives.”

AI offers the promise of a better life, but like the Kanamits, something may be off. At the end of the episode, Michael Chambers got the good news. He finally got his ticket, and he was going to the Kanamit planet. But standing in line waiting to board the rocket ship, his assistant suddenly approached and warned him not to go. Because his team finally translated the book, the Kanamit representative left that day after speaking with members of the United Nations.

He had to know, but it was too late. Because that book “To Serve Man” was a cookbook. While the Kanamits force-feed him in preparation for the big meal, he turns to the camera to warn the audience,

“You still on earth or on the ship with me? Well, it doesn't make very much difference because sooner or later...We'll all of us be on the menu...All of us.”

As the light fades on his sorry fate, the narrator closes the scene,

“The recollections of one Michael Chambers with appropriate flashbacks and soliloquy. Or more simply stated, the evolution of man, the cycle of going from dust to dessert, the metamorphosis from being the ruler of a planet to an ingredient in someone's soup.”

The world certainly hopes that is not the case for AI.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2025, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief

This Month’s Chart Deck

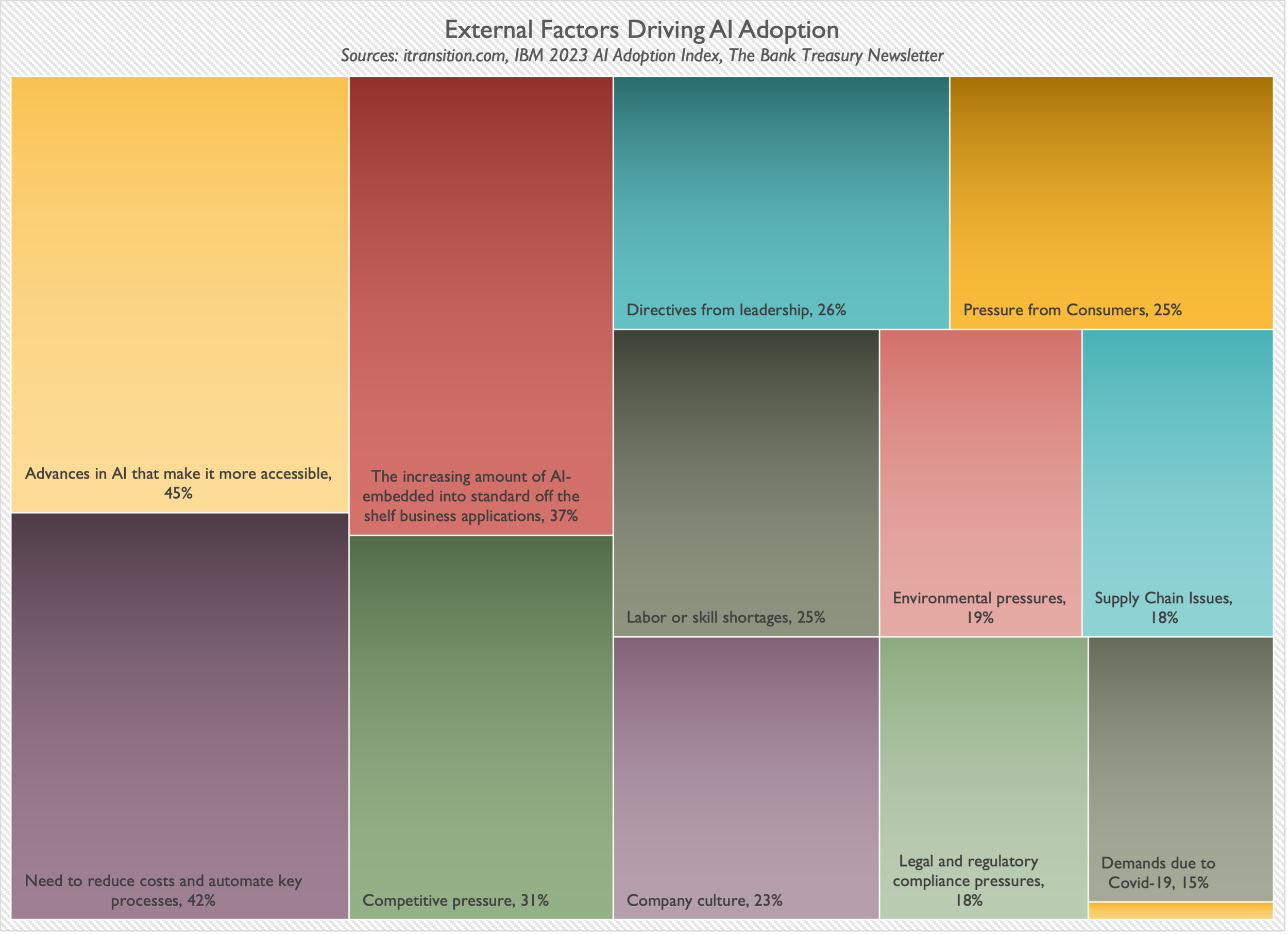

From the largest to the smallest banks, finding scalable and identifying profitable opportunities to integrate the latest artificial intelligence (AI) technology into operations is among every bank treasurer’s list of top priorities for 2026. Adoption at this stage is still experimental, but the key thing is that familiarity with the technology breeds more opportunities to incorporate it that may not be obvious at the outset. Building on the discussion in this month’s newsletter, the slides in the chart deck examine the use cases bank treasurers can already see for it, the general uncertainties and reservations they have about it, and the economics and realities that are pushing them towards and away from adoption.

One of the top reasons senior business executives give for not wanting their staff to use Gen AI is that it will sap creativity (Slide 1). But for central banks (including the Fed, the ECB, the Bank of England, the Bank of China, and the Bank of Japan), where economists rely on data management and analysis to do their work, AI technology is a godsend, which they view as helping them with payments management, economic analysis, and bank supervision (Slide 2). The public is still skeptical, and the majority opinion that AI could help with creative thinking, problem-solving, complex decision-making, or even serving as a companion is a definite no (Slide 3).

AI adoption comes at a cost, as electricity to power data centers increases demand and raises consumer prices (Slide 4). That demand will increase because data suggest the technology could be more popular than the PC was when it entered the mass market 40 years ago (Slide 5). The most-cited tasks workers report using AI for are creating communication content, followed by performing administrative tasks and summarizing documents (Slide 6). One thing users see is how much time AI saves them (Slide 7), especially when they use it regularly. Economists believe that AI will power economies (Slide 8), assuming it does not lead to a great AI singularity that replaces all humans.

The technology is more user-friendly, one of the top reasons executives give why they have increased their focus on this topic, looking for ways to put it to good use in their businesses (Slide 9), but one of their top reasons holding them back is that they worry they do not have the right talent in their institutions to execute (Slide 10).

What Worries You Most About AI?

AI Use Cases For Central Banks

Jury Is Still Out On AI

AI Strains Power Supplies And Raises Costs

AI More Successful Than The PC 40 Years Ago

Top AI Use Cases

AI Saves Time

AI-Powered Prosperity

What’s Pushing You?

What’s Stopping You?