BANK TREASURERS IN ENDTIMES: SEASON TWO

The bank treasury world is a blur of headlines this month, generated mainly by the President of the United States. For example, he directed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to bring down mortgage rates. Commercial banks own more than half of the outstanding Agency MBS, totaling $2.7 trillion, much of which is underwater in available-for-sale portfolios or locked away in held-to-maturity portfolios. The Fed owns another $2.0 trillion, and insurance companies hold $1.0 trillion.

But mortgage rates are already down from their peak in 2023, when the rate on a new 30-year mortgage topped 8% versus just over 6% today. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac combined total assets equaled $8.0 trillion as of September 2025, including $300 billion in investment securities and repo. These agencies have no equity capital supporting their balance sheets, and buying MBS was a contributing factor in their troubles during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), after which they were seized by the Treasury and placed into conservatorship. Buying MBS would likely complicate the Administration’s plan to recapitalize them and return them to the private sector.

He demanded a 10% cap on credit card loans for one year, although details beyond the headline remain unavailable, especially how he could enforce it. Technically, his order carries little legal weight as state usury laws apply to credit card rates. Since banks price loans based on risk, capping rates at 10% when the standard credit card rate is more than twice that would mean they would need to underprice for risk and raise their own risk profiles to meet this demand. The industry held $1.2 trillion in consumer credit card loans on its balance sheet in Q3 2025, of which half was on the books of the four largest banks. Bank executives at these institutions predicted during their quarterly calls with analysts this month that price control ideas like the President’s would end badly.

He escalated his feud with the Fed and campaign to compromise its independence, reminiscent of the feud between the White House and the Fed that led up to the 1951 Treasury accord. In the middle of his own renovation plans at the White House, he directed the U.S. Justice Department to investigate Chair Powell over Congressional testimony he made about renovations underway at the Fed’s headquarters. He is also preparing to name the Chair’s replacement. This month, the Supreme Court will hear his case against Fed Governor Cook, whom he attempted to fire last year. Fed Governor Marin, who is serving on an interim basis, will step down at the end of this month following the FOMC meeting. He took the position when former Fed Governor Kugler resigned last year and her term ends this month. The President will have three open seats at the Fed to fill.

Miki Bowman, whom he appointed as the Fed’s Vice-Chair of Supervision, continued her campaign to rein in the Fed’s examination force. According to a published memo sent by her acting head and deputy head of bank supervision at the Fed’s Board of Governors, examiners must focus on “material risks” over issues described as “processes, procedures, and documentation that do not pose a material risk to a firm’s safety and soundness.” Further reining in the Fed’s exam force, the memo told examiners that they can no longer conduct their own exam unless it is “impossible for the Federal Reserve to rely on the examination of such a depository institution’s primary state or federal supervisor.” Meanwhile, the Fed, FDIC, and OCC are in the middle of a reduction-in-force, begun last year, to cut headcount by 10%, potentially compromising the capacity of bank supervision to conduct timely exams.

These new marching orders come at a sensitive time for the banking industry with the shift to instant payments and intensifying consolidation. Going solo without the other members of the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, including the Fed and the OCC, the FDIC, under its newly confirmed chairman, Travis Hill, published its own guidelines for applicants to set up a stablecoin-issuing subsidiary under the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act (GENIUS). The Fed issued a Request for Information to the banking industry on establishing a new account for noninsured financial institutions to accommodate their payment and settlement needs and help foster innovation. Last month, the OCC approved an application from First National Digital Currency Bank, owned by the Circle Group, to establish a trust bank to issue stablecoins under the GENIUS Act. The President’s order to the U.S. Mint to cease production of the penny coin is leading to shortages, and to help ease some of the stress at retailers, the Federal Reserve announced this month that it will resume accepting pennies from banks and credit unions, a service it had previously suspended.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

Season two of the video game-inspired streaming television show, “Fallout,” dropped last month just in time for the holidays. The billboards around Los Angeles continue to advertise and celebrate the much-anticipated return of the post-apocalyptic series with the rollicking tagline “Let the Endtimes Roll.” But how can Endtimes have a second season, much less rollick or roll anywhere? Because the end times should, by definition, be pretty final. The end is the end.

But it never ends there, and for obvious reasons. Bank treasurers know this truth so very well, because the end would be great as far as some of them sometimes are concerned, at least in their quieter moments. At least the torture would stop. Because it is always End Times, Season Two in bank treasury.

Honestly, bank treasurers should be so lucky to have no tomorrow, because the end times are miserable precisely because they do not end. You wake up the next day and every day after that feeling only more pathetic than you were the day before, with the knowledge that you have more to deal with when you get to the office.

The yield curve is flat to normal today. It might steepen further this year. We might have a normal yield curve. Can you imagine? But for most of the last few years, it was inverted, which is supposed to be existential for the economy and banking, no? Inverted means we are doomed. And anyway, how can bank treasurers borrow short and lend long when lending long yields less than borrowing short? How can banking exist in such harsh conditions, with uncertainty and so much unknown?

How can the model work when the rates are the same long and short? Given the intense competition for loans, how can banks make money for shareholders on ever-narrower spreads? And where do bank treasurers even find the nerve to call their deposits “core” anymore, when soon every financial instrument will come in token form and deposits capable of withdrawal in an instant?

But bank treasurers work in all conditions; it is just harder in some of them than others. Like the characters in sci-fi thrillers, they learn to adapt even in the harshest conditions. They make it all work, which is why they are real bank treasurers, moving through their own version of an apocalyptic hellscape, oblivious, or possibly blind to the dangers all around them.

End times are a popular subject in television, and its main characters always live to see another season. The end does not only have a second season. Successful showrunners are always thinking ahead when a show debuts about a season three and four.

After all, The Walking Dead (TWD) squeezed in eleven whole seasons out of the zombie apocalypse. In fact, if you sum up all the episodes in each season of TWD, you get 177 episodes, each running about an hour. We are not even counting the spinoffs. Yes, the spinoffs, as in “Fear the Walking Dead,” “The Walking Dead: World Beyond,” “Tales of the Walking Dead,” “Dead City,” and the hopeful, “The Ones Who Live.”

Then there are the remakes. Remakes of apocalyptic stories go back a long way in the entertainment industry. In fact, TWD itself was a television series remake of the old George Romero horror classic, “Night of the Living Dead,” which he then remade into the “Dawn of the Dead,” the ”Day of the Dead,” the ”Land of the Dead,” the ”Diary of the Dead,” and his final installment, the “Survival of the Dead.” There is no such concept as “deader than a doornail” in the end-times business. As the robot Sebastian explained to the mutant ghoul Cooper Howard last season on “Fallout,”

“The end of the world is a product. And for those of us who can successfully embrace that, I'd say the future is golden.”

Endtimes With No End

It is always endtimes. Every year is the year everything collapses. Predictions about how the market ends are endless, and it always ends the same way. The economy will collapse in 2026 because the tariffs will finally kick in and get passed on to consumers, who will all lose their jobs to artificial intelligence (AI) and stop spending.

Or inflation will prove sticky, and consumers, already reeling from skyrocketing health insurance costs, will stop spending. Or the Fed will make a mistake and cause a recession, killing jobs and spending. Or interest rates will hurt businesses, which will stop spending and hiring, which will cause consumers to stop spending, which will then feed into a doom loop when businesses retrench, and consumers cut back. Or 2026 will be the year when markets finally choke on U.S. Treasurys. Then watch out, as former Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned this month, with talk of red lines and the end of the Roman empire. Armageddon and apocalypse are always around the corner.

Or geopolitics and future uncertainty cause consumers to stop spending. Maybe 2026 is the year that China finally invades Taiwan? Or the U.S. invades Greenland? Or how about a climate disaster or another pandemic trips up economies and markets? Or a cyberattack on the energy grid brings the world to a halt, as former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta once warned, or just worrying about it will cause problems, or some computer Y2K glitch sends the world back to the Stone Age. Or the world will run out of oil as William Steven, Exxon's former CEO, predicted in 1989 would happen by 2020, and experts again predicted in 2003.

Bank treasurers are always facing endtimes in their line of work. A few years ago, office vacancies were going to cause an imminent financial crisis, and high interest rates were going to be a ticking time bomb for real estate owners. In 2020, the banking system adopted Current Expected Credit Loss, and many bank treasurers in 2019 sought an indefinite delay, fearing the accounting rule alone would be the end of banking, or at least make their lives a lot harder.

The end of the London Interbank Offered Rate and the rise of the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) were going to seize up the leveraged loan market if the risk-free rate were to go 0% while credit fears spiked. Bank treasurers are still worried about the end-of-times level of negative Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income in their bond portfolios, which will cripple their liquidity.

Yesterday, money markets were going to rule the world and disintermediate the banks. Today, the U.S. banking industry holds 72% of its deposits on its balance sheet in commercial loans. Tomorrow, discounted stablecoins will disintermediate it and precipitate a financial crisis. But bank treasurers will soldier on because they have to, and as a global bank’s CFO told analysts this month,

“Geopolitical is an enormous amount of risk…It may determine the fate of the economy. The deficits in the United States and around the world are quite large. We don't know when that's going to bite. It will bite eventually because you can't just keep on borrowing money endlessly…We have to deal with the world we got, not the world we want.”

The economy's strength is its weakness. The AI bubble that drove the economy and markets will burst, exposing its delusional overpromises. Promises for a brighter tomorrow, promises for endless growth and cost savings that will lead to more jobs, not less, and pledges that reality will never catch up with those overpromises and cause the the market to crash one fine morning out of the blue. One day, investors will unload their holdings in Nvidia, the market's highest valued stock, which will take the rest of the market down with it, and cause a recession that will put a stake in consumer spending, in a grand replay of the fall of the Radio Corporation of America, the Great Crash, and the Great Depression that followed.

Bank treasurers have seen it all before. Every year is the same because end times are cyclical or rhyme. What goes up goes down, and if last year's stock predictors forecast a correction that never came, it will for sure come this year, or next year, or for sure the next one. Nothing can go on forever, even lucky streaks and economic expansions that every year defy the doomsaying for one reason or another. Never say never, as the late economist Irving Fisher learned the hard way when he famously opined just before the Great Crash,

"Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau."

Because the price of equity cannot go to infinity, those in the prediction business can always say with confidence that the sky will fall tomorrow. We are always overdue for a recession, for a market correction, or just a traditional mark-to-market in overvalued property markets, where office loans are in trouble and multi-family developers are hopelessly over-extended. But then the sun will come out the next day after tomorrow, because even endtimes have goodtimes.

Cyclical Predictions

Samuel Benner was a farmer who lived in Ohio in the second half of the 19th century. He studied market cycles dating back to 1780 and, in 1872, published his market predictions extending to 2059. Though you would not want to put money on his calls, Benner’s cycles called the 1929 crash and the GFC, though his Crash would have been in 1927 and his GFC in 2007.

According to his theory, booms and busts repeat in cycles every 18, 16, and 20 years. There are years when market “panics occur and will occur again,” years of “good times, high prices, and time to sell stocks and value of all kind,” and then there are years of “hard times, low prices, and a good time to buy stocks, corner lots, goods, and etcetra, and hold till the boom reaches the years of good times; then unload.”

If you listen to Benner, we are in the middle of his 18-year cycle, and the last panic was in 2019. Hard times are not until 2035. The good news is that 2026 is supposed to be peak good times, which certainly has a ring to it with equity markets, commodity markets, and all manner of value at sky-high levels. So, there is a time to reap and a time to sow. Let the goodtimes roll!

A century ago, Nikolai Kondratiev, a Russian economist, published his controversial theory of long historical economic cycles that overlap with shorter business boom-and-bust cycles. Each of his K-waves, as economists call them (and not to be confused with K-waves that refer to a Korean cultural transcendence), lasts about 50 years, plus or minus a year or two or three, driven by technological advances, geopolitical shifts, or other economic changes. Even if things slow down while a K-wave is still growing, they do not stay that way for long, and even if things speed up, they eventually fall back under the wave.

The world is clearly in a growth phase, as the chairman, president, and CEO of a large regional bank based in the southeast observed this month on his quarterly earnings call, assuring analysts that loan growth had a bright future regardless of the uncertainties,

“The momentum in the economy appears to be very good today. I think, as uncertainty emerges, whether it be, Venezuela, Iran or oil prices or whatever the uncertainty could possibly be, people will take stock, but I think people are generally biased for growth and so I expect C and I will improve.”

K-waves have four phases corresponding to the seasons of the year: spring, which K-wave enthusiasts believe we are in now, when prices are rising, economies are growing, and the futures are forever brightening, summer, when prices are overheating and the economy is stagnating, fall, when prices are starting to fall and finally winter, when the economy is in recession and collapsing.

The first K-wave began around the year 1800, coinciding with the start of the Industrial Revolution. Steam engines drove, and textile looms dressed factory workers. Around the 1820s, the growth trend began to falter, culminating in a series of panics and recessions that led to the Civil War. The steel and rail industry drove economic growth in the second half of the 19th century, and ended in the Panic of 1907 and then World War I. Then came the mass-production K-wave, which gave way to cars and then to information technology in another K-wave in the second half of the last century. We are just at the start of the sixth K-wave, where AI, nano-tech, and healthcare still promise a brighter tomorrow.

It’s Always Endtimes for the Fed

The Fed’s independence is constantly under threat, its political status waxing and waning in tune with some version of a Brenner cycle or K-wave. It gets stronger in times of crisis, when it assumes powers such as quantitative easing that balloon its balance sheet multiple-fold beyond what its founders could have ever imagined. Its powers wane after a crisis passes, as the public begins to chafe under its heavy hand in the economy and markets, and calls for accountability and transparency grow louder to rein it in. Success breeds failure, and out of the ashes it rides again. Right now, however, its days seem numbered.

Today, the Fed we know and love is at risk, and if it goes, the world, as far as bank treasurers are concerned, will end. There is no hope. President Trump will install a new Fed chair this year, to his Treasury Secretary’s liking, who will cut interest rates regardless of whether or not they warrant cutting, and that will be that. Recalcitrant Fed governors better watch out, and even Fed presidents who are appointed by the boards of the individual regional Feds and approved by the Board of Governors, which is appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, who serve as alternative voters on the FOMC, are not safe in their seats.

Terrible! As the chairman, president, and CEO of one of the four largest global banks in the U.S. told an interviewer last month,

“The market will punish people if we don’t have an independent Fed.”

We are doomed. His words echo what another influential senior bank executive said back in the summer,

"The independence of the Fed is absolutely critical, and not just for the current Fed chairman, who I respect, but for the next Fed chairman…Playing around with the Fed can often have adverse consequences, absolutely opposite of what you might be hoping for.”

With inflation still above the Fed’s 2% target, if it cuts the Fed funds rate aggressively the way the Administration demands, it will blow its credibility. Goodbye to a presumption that its monetary policies have any ulterior motive other than the economy’s well-being, with stable prices and maximum employment. It is time to head for the hills as Treasury yields hit the ceiling because Treasury markets are doomed. We are all doomed. Yet, threats to the Fed’s independence are nothing new, and in fact go back to the first Independence Day, 250 years ago, when it was just a glint in the first Treasury Secretary’s eye.

Political independence sounds like a no-brainer. Of course, you do not want politicians meddling in technical details entailed in the Fed’s conduct of monetary policy, or trying to prevent it from looking out for the long-term interests of the economy politicians and bankers designed it to support. Most people in this country (at least bank treasurers hope) get that powerful politicians should not force the Fed to bend to their wishes to manipulate interest rates up or down (usually down) for their short-term particular benefit or the benefit of constituents. That cannot possibly sound to them like that will end well in the long run. The Fed should manage interest rates solely to stabilize prices and maintain full employment.

But this aspiration ignores a few realities, both practical and political. Practically speaking, the Fed is a creature of the politicians who created it. As one writer called it, the Fed is “The Creature From Jekyll Island.” What ultimately evolved into the Fed we know today was the brainchild of a group of senior bankers and the then head of the Senate Finance Committee, Nelson Aldrich, who met in secret in 1910 on a secluded golf course off the coast of Georgia. And what legislators giveth they can taketh away. There is nothing sacrosanct about the Fed and its independence.

For the record, until 1935, the Treasury secretary sat and was a voting member of the FOMC. Even after that, it was not as if the FOMC had much say about interest rates, which they patriotically and dutifully suppressed, keeping long-term debt yields at 2.5% during the war years. Threatening the Fed’s independence has always been a bipartisan pursuit by officials of the executive branch.

Trump is not the first president to threaten its independence and will not be the last. Following World War II, Harry Trumandemanded that the Fed target rates to help the war effort against North Korea and China. Raising rates was tantamount to aiding the communists, or, as Truman said in 1950,

"…exactly what Mr. Stalin wants.”

Or as Trump goaded Jay Powell, who he appointed in 2017, and was confirmed in 2018, at a press conference in 2019,

"My only question is, who is our bigger enemy, Jay Powel or Chairman Xi?"

Tom McCabe, who was the Fed chair in 1950, tried to explain to Truman why he could not guarantee successful debt auctions if the Treasury were willing to pay no more than the then-raging high inflation rate, according to the Minneapolis Fed. Instead of leaving the Fed alone, Truman shot the messenger and fired him.

The Treasury accord of 1951 was born from the confrontation between Truman and McCabe, which established a Chinese wall between the Government’s financing needs and the Fed’s conduct of monetary policy. But that was not the way Lyndon Johnson and, after him, Richard Nixon saw the Fed’s role. Both belabored, hectored, and intimidated Fed Chair Arthur Burns to hold rates down even as inflation from their guns-and-butter policies stoked the inflation monster. For that matter, Ronald Reagan did not exactly have a great relationship with Paul Volcker, and maybe that was why, in 1987, as soon as he could, he replaced him with Alan Greenspan.

He was not alone. Don Regan, his Treasury Secretary, was blunt with his senior staff at a meeting,

“I don’t know why we need an independent Federal Reserve Board.”

The Fed is the devil, as Republican Congressman George Hansen from Idaho railed in the early 1980s when it had interest rates in double-digits,

“We are destroying the small business. We are destroying Middle America. We are destroying the American dream.”

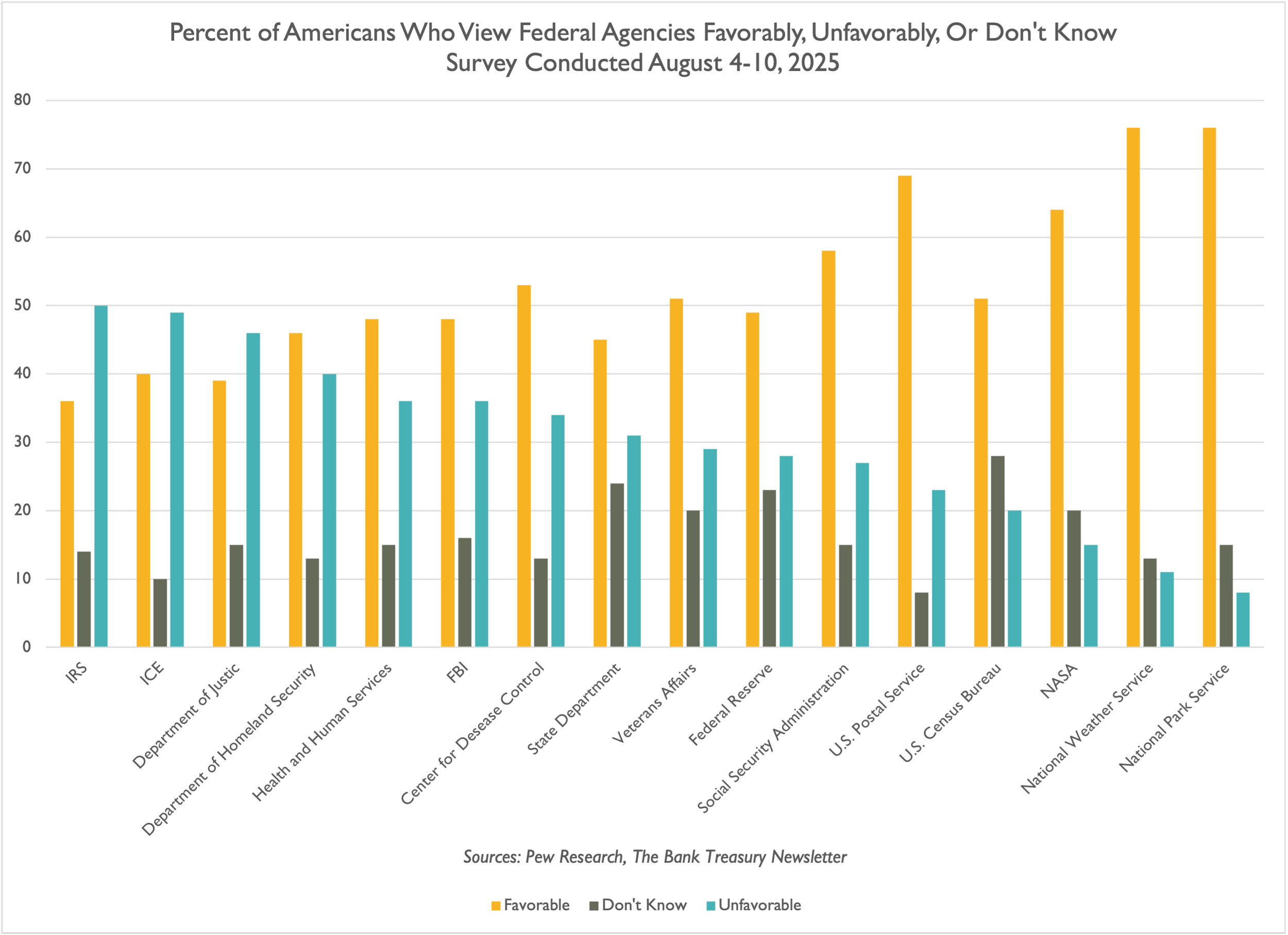

History is not on the side of Fed independence, and yet, it will probably muddle through the current storm. It will learn to adapt because that is what it has always done. Plus, politically speaking, the public is not going to care, and the Fed is not exactly a super popular institution with John Q. Public, so it is on its own, living with the new order. According to a 2025 Pew Poll, for example, the Fed is not high up in the public’s esteem even if it does not rank as low as the Internal Revenue Service (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percent of Americans Who View Federal Agencies Favorably, Unfavorably, Or Don't Know

Plus, it is not like the Fed is doing a bang-up job with the economy or the markets to encourage politicians to leave it alone. "Got it" does not mean you call inflation temporary when it was clearly something much scarier. "Got it" does not mean that a few months before you start raising rates in your December 2021 dot plot, you suggest that rate hikes will go slow and easy, but a few months later, you turn them into fast and hard. “Got it" does not mean you take four years with a restrictive monetary policy to bring inflation back into line with your 2% long-term inflation goal and wait for the lag effect to kick in for so long that Vladimir and Estragon never waited so long for Godot.

"Got it" does not mean after failing to bring inflation back in line with 2%, you surprise the markets in September 2024 and inexplicably cut the Fed funds rate by 50 basis points, and then cut by 25 basis points twice more before the end of 2024 for a total of 100 basis points. The market was certainly not impressed with the Fed's grasp of the fundamentals, which is no doubt why the yield curve bear steepened in response to the cuts, something that has never happened in any previous cutting cycle going back nearly 40 years. "Got it" does not mean having a 12-member FOMC group vote split its votes in favor and against cutting rates, looking at the same data as it did last month.

If the Fed tells the public to trust it, it has to deliver. It has to. Otherwise, maybe it is not such a bad idea that politicians rein it in.

The Fed's very structure speaks to the delicate compromise between Fed independence and political influence. Because, politically speaking, the Fed cannot act like a bunch of philosopher-kings out of Plato's Republic, who the unknowing public must leave alone and still pay to do their thing without answering any questions from the People's representatives or meeting any yardstick. This country is a democracy, afterall. The People will ultimately dictate the price of money.

And not only do presidents try to assert political control. In 1993, for example, Congressman Henry Gonzales, chairman of the House Banking Committee, tried to change the Fed's structure to allow Presidents to appoint the Fed's presidents, or at least to strip them of their voting rights. As Senator Paul Sarbanes of Sarbanes-Oxley fame pointed out in support of his proposal,

"Although most Government agencies, including the Fed, make extensive use of private citizens as advisers, in no other agency is actual decision-making power vested in individuals who are formally accountable to private parties instead of to the public."

Fed Independence: Let Freedom Ring

Go back 250 years, and the same debates raged. Alexander Hamilton, the nation's first Treasury secretary, no less, was a big believer in an independent central bank, and he pushed George Washington, over Thomas Jefferson's objections, to sign the legislation that created the First Bank of the United States. The bank would be 80% owned by the bankers and 20% owned by the Treasury. It could issue its own money, and the Treasury would leave its money on deposit with it.

But it was also an institution that, as discussed in a Kansas City Fed study, concentrated power in the hands of Northeastern bankers and merchants to the disadvantage of farmers in the South. Chartered for 20 years in 1792, it came up for renewal in 1812, when Thomas Jefferson's protégé and fellow farmer, James Madison, was president, and he refused. British investors in the bank probably did not help its cause. But in 1816, dealing with the aftermath of the War of 1812 and the burning of the White House, and maybe trying to figure out where to put the ballroom in the new White House, he decided that Hamilton was right and rechartered the bank.

An independent central bank is a bank that stays out of political trouble, as Nicholas Biddle, President of the Second Bank of the United States, once said,

“There is no one principle better understood by every officer in the Bank than that he must abstain from politics. We believe that the prosperity of the Bank and its usefulness to the country depend on its being entirely free from the control of the officers of the Government, a control fatal to every bank which it ever influenced. In order to preserve that independence it must never connect itself with any administration – and never become a partisan of any set of politicians.”

Biddle was an innovator, instituting what today the Fed calls open market operations to buy and sell securities from the public to ease or tighten credit availability. Unfortunately, Biddle did not listen to his own advice and got involved in a political feud between Speaker of the House Henry Clay and Andrew Jackson, a feud that Clay ultimately lost. But it did not help his cause that the commercial bankers at the time hated it.

Frankly, the bankers were jealous because they wanted to hold the Treasury’s deposits. But doing business directly with the public was not a great way to win their favor, either and that was exactly what Biddle was doing. Jackson, for his part, was adamantly against it, as he told Congress right after he got elected President in 1828,

“Both the constitutionality and the expediency of the law creating this bank are well questioned by a large portion of our fellow citizens, and must be admitted by all that it has failed in the great end of establishing a uniform and sound currency.”

Jackson was determined to kill the bank at any cost. In 1833, he withdrew the Treasury’s funds from the Second Bank of the United States and deposited them in politically aligned private commercial banks. That will show them, he told Vice-President Martin Van Buren,

“The Bank … is trying to kill me. But I will kill it.”

In 1836, the Second Bank of the United States passed into history. Actually, after it lost its charter, the bank became a private bank, which Biddle called the United States Bank of Pennsylvania. But only five years later, what was once one of the most powerful financial forces in the country failed when the bottom fell out of the cotton market, and its loans defaulted.

Endtimes for the “M” in “CAMELS”

The Fed’s independence problem does not just end with its conduct of monetary policy. Politicians are bipartisan in their views about its performance as a bank supervisor, too, and they are not good. And for good reason. The Fed is one of three Federal authorities that supervise banks, along with the FDIC and the OCC, and often all three agencies, in addition to the institution’s state bank supervisor, conduct overlapping exams.

Supervision is a resource-constrained activity, as the Fed and other examination agencies perennially struggle to attract and retain staff to help prevent the next bank crisis. A 10% reduction-in-force pushed by Trump adds to its constraints, and thus, bank supervision struggles to fulfill its mission of preventing the next bank crisis. But resource constraints are only part of the problem; it could also improve its communication skills.

There is a lot to bank exams that are opaque because examination communications are secret, but often the examinees are confused by their examiners. Poor bank treasurers sometimes find themselves duplicating the same work for one agency and another, and dealing separately with competing requests. Sometimes, what passes muster with one bank examiner in one agency, another examiner at another agency will find wanting; sometimes examiners from different agencies will offer conflicting guidance, and sometimes they will slap an institution with a formal complaint, such as a Matter Requiring Attention or Matter Requiring Immediate Attention, without clearly explaining the steps needed to clear them.

And there are so many exams, too, horizontal exams, liquidity exams, compliance, consumer lending, and safety and soundness, to name a few, which overlap and are duplicative. When they finish all that, the auditors will usually be waiting for them in the conference room.

Bank supervisors could also spend some time reviewing existing regulations for relevance. Because sometimes the problem a rule on the books addresses no longer exists or is different. After a bank crisis, bank supervisors write many new regulations to plug holes they think led to it, and then spend all their focus identifying any activity that sounds suspiciously like what caused the last crisis. Then comes another crisis, and they write more rules and add more pages in the exam manual because no two crises are ever the same.

The bank supervision story is as cyclical as a Brenner cycle or a Kondratieff wave. Right after a crisis, supervisors get tough, and a few years after, they ease back. Politicians pass laws to beef up the Fed’s powers and then pass laws trying to strip the Fed of its supervisory powers.

Sometimes the political issue is personal. No one likes the Fed examining banks. In the aftermath of the GFC, which the Fed, with its risk-based capital rules, failed to prevent, Senator Chris Dodd, of Dodd-Frank fame, pushed but was unable to cut the Fed out of supervision. Today, the Fed’s supervisory effort, led by its Vice-Chair, Miki Bowman, is working to do precisely that. As she said this month, there is a new sheriff in town in bank supervision,

“Since the mortgage crisis more than 15 years ago, bank regulation has been implemented under an overly granular "more-is-better" approach that has driven significant banking activity out of the regulated system and into less-supervised corners of the financial landscape. This framework is long overdue for a comprehensive review. An unfocused, process-heavy approach to regulation and supervision leaves banks less able to support economic activity, displaces activity into unregulated sectors, and ultimately makes the overall financial system less safe and stable.”

A New Bank Sheriff in Town

From now on, as the acting and deputy acting director of bank supervision stated in a memo about operating principles for bank supervision as dictated by its Vice-Chair, the Fed will get back to basics. Basics are not subjective assessments based on matters unrelated to the bank’s material health and well-being; all that business about climate and gender is gone from the examiner training program. Basics are about numbers and material facts; they are not about processes and form over substance.

Bank examiners are not some kind of Marine boot camp drill sergeant making recruits do push-ups because of a crinkled bed sheet. They are supposed to ensure the bank can shoot straight, which means they have the numbers to back it up. Who cares if a manual is outdated? On the other hand, tell it to the Marines for whom form is substance.

From now on, Fed examiners cannot just conduct bank exams on their own. They have to rely on the FDIC and OCC exams as much as possible. Excuses such as “they do it differently” from those examiners will no longer be a valid reason for a Fed bank examiner to conduct their own exam.

Also, just because a bank examiner has a good idea does not give them the right to conduct an exam to see whether the bank followed their guidance. From now on, Fed examiners will need to take management’s word for it to cross it from their list of to-dos. And all that business discriminating against Federal Home Loan Bank advances and favoring bank treasurers pre-positioning collateral at the discount window ends right now.

The last line in the memo is the kicker:

“The management and risk management components of CAMELS…should not be given more weight than the other components in determining a firm’s composite rating. All component ratings should be considered and weighed based on their materiality to the institution.”

So, we got the memo, but let's see if we understand it. Let's say you are a 24-year-old who got lucky enough to be hired by the Fed as an intern in its examiner training program out of college. Your examiner-in-charge (EIC) on a bank exam to which the Fed assigned you is about five years older and was just promoted into the role after a 20-year veteran examiner left last year when the Fed began reductions in force.

You see something, and you want to say something. Management at the bank either does not understand why you are making a big deal or does not want to be bothered, but you know that their actions are reckless. Yes, it is a little about form over substance. The bank's compliance manual's human resources section is a year out of date. You learned to spot these kinds of red flags in the examiner training class. You bring the matter to your EIC's attention, and the EIC escalates the matter to the examiners at the FDIC or OCC, who, because of staffing shortages, cut back on the exam schedule this year and will not be in the bank until next year or maybe the year after. Now what?

Does anyone remember these comments from the Silicon Valley Bank post-mortem, page ii?

“Overall, the supervisory approach at Silicon Valley Bank was too deliberative and focused on the continued accumulation of supporting evidence in a consensus-driven environment. Further, the rating assigned to Silicon Valley Bank as a smaller firm set the default view of the bank as a well-managed firm when a new supervisory team was assigned in 2021 after the firm's rapid growth. This made downgrades more difficult in practice.”

Which does not necessarily mean that the changes the vice-chair of supervision is pushing are bad. Institutionally, the Fed does tend to add more rules to address problems rather than first establishing that the rules already in place still work. Supervision is a two-way street and requires cooperation with the supervised. There is nothing wrong with extending the benefit of the doubt and leaving management to do its day job.

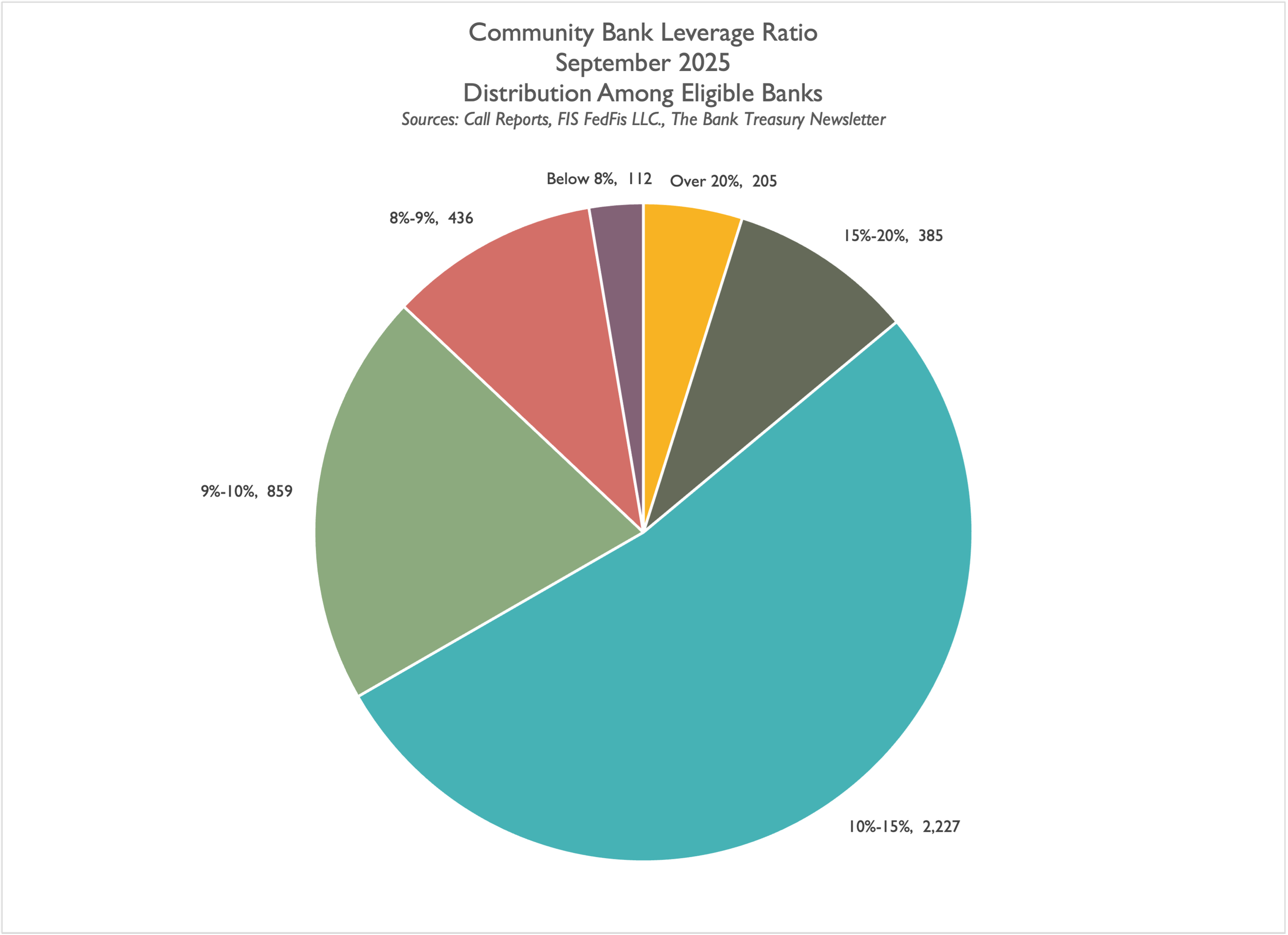

It makes sense to tailor bank regulations based on a bank's size. Community banks are different from the large behemoth banks, which, if they failed, no doubt would be the end of the global financial system. But whether the Community Bank Leverage Ratio (CBLR) minimum threshold should be 10% as regulators conceived initially, 9% as they eventually decided, or 8% as they now propose makes very little difference to the overall picture of the community bank industry. Lowering the ratio from 9% to 8% would bring 436 banks into compliance, which reported a leverage ratio between 8% and 9% at the end of Q3 2025, about 10% of all commercial banks.

Phillip Basil, the director of economic growth and financial stability at Better Markets and a former Fed official, had no kind words for the moves to ease what many bankers believe is a regulatory chokehold on their industry, telling a reporter for Bloomberg Law,

“This essentially dismantles bank supervision as we know it.”

Stablecoin Endtimes

Bank treasurers welcome the brushback on bank supervisors. As far as they are concerned, the move is long overdue. But they still worry that pulling back the beat cops when the industry faces so many rapid changes could cause the next crisis, which will just lead to more bank rules in another bank supervisory cycle. Exhibit A is the rise of stablecoins and instant payments. As a Fed research note discussed this month,

“As these digital tokens gain mainstream acceptance, they could fundamentally reshape the structure and functions of banking and influence the established intermediation role of banks.”

Changes are already underway. Under the (GENIUS Act), last month, the FDIC proposed procedures for banks to establish subsidiaries to issue stablecoins. Contributing to confusion when least helpful, the Fed and the OCC did not join the FDIC’s proposal, which is strange, since they would also approve subsidiaries for which they are the primary supervisor, not the FDIC. As for form and substance, form is a big part of the requirements that an applicant must meet for approval. As an excerpt from the FDIC’s proposal notes,

“Policies and procedures such as those related to custody and safekeeping, segregating customer and reserve assets, recordkeeping, reconciliation, and transaction processing would be relevant for the FDIC to evaluate the financial condition and resources affecting the ability of the subsidiary to meet the requirements…to maintain the proposed payment stablecoin’s stable value or reasonable expectation thereof, the ability of the subsidiary to meet customer redemption requests, and the accuracy of public disclosures of reserve assets.”

Stablecoins are not the only change in the bank treasury landscape. The Fed plans to create a special payment account for noninsured financial institutions. The account would not include all the bells and whistles of the master account commercial banks get, but, as Board Staff explained in a Request for Information it published last month, the new account would help foster innovation. But potentially it would increase complexity in a system that is already very complex and difficult to supervise as the 2023 stress event in regional banks demonstrated. The fallout if something goes wrong is unimaginable.

The unimaginable tends to become all too real these days. A criminal investigation by the Justice Department into the Fed Chair and the refurbishment he has overseen of the Fed headquarters in the Eccles Building, named after the Fed chair appointed by Franklin Roosevelt and who spearheaded the 1951 Treasury Accord, just adds to the chaos of the times. The End Times are here. The end of everything. But all that comes with the territory, where the endtimes roll year after year, and 2026 will be no exception. The Fed has been here many times, and so have bank treasurers. Let the endtimes roll.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2026, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief

This Month’s Chart Deck

As initially proposed by regulators, the minimum threshold for the Community Bank Leverage Ratio (CBLR), which equates to the Tier 1 leverage ratio, was 10%. Commercial banks with less than $10 billion can opt to report the Tier 1 and total risk-based capital ratios. When they finalized it in 2019, however, they lowered the minimum to 9%, and late last year, they proposed reducing it further to 8%. As of September 2025, the CBLR for 10% of all CBLR-eligible institutions ranged from 8% to 9% (Slide 1).

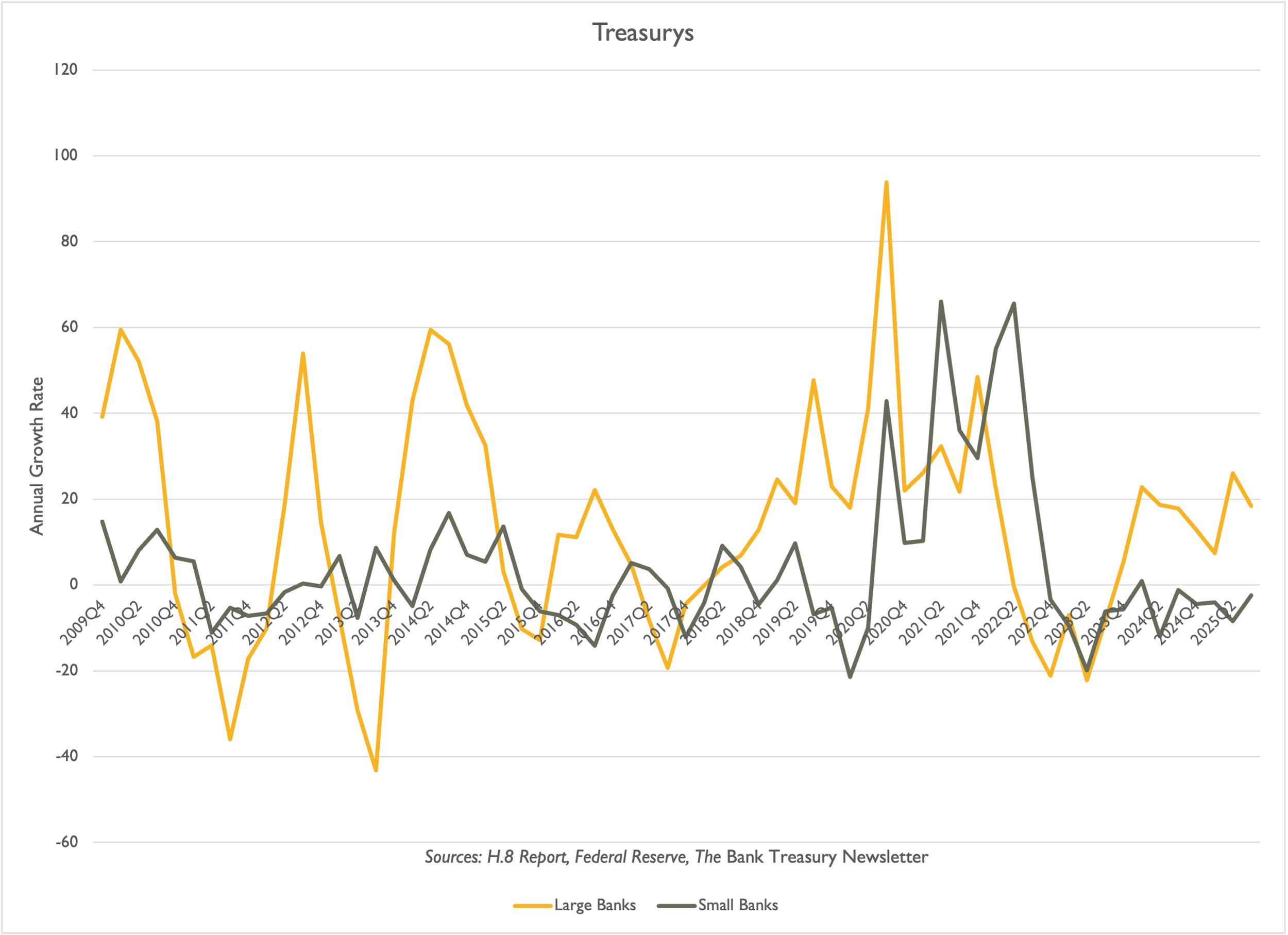

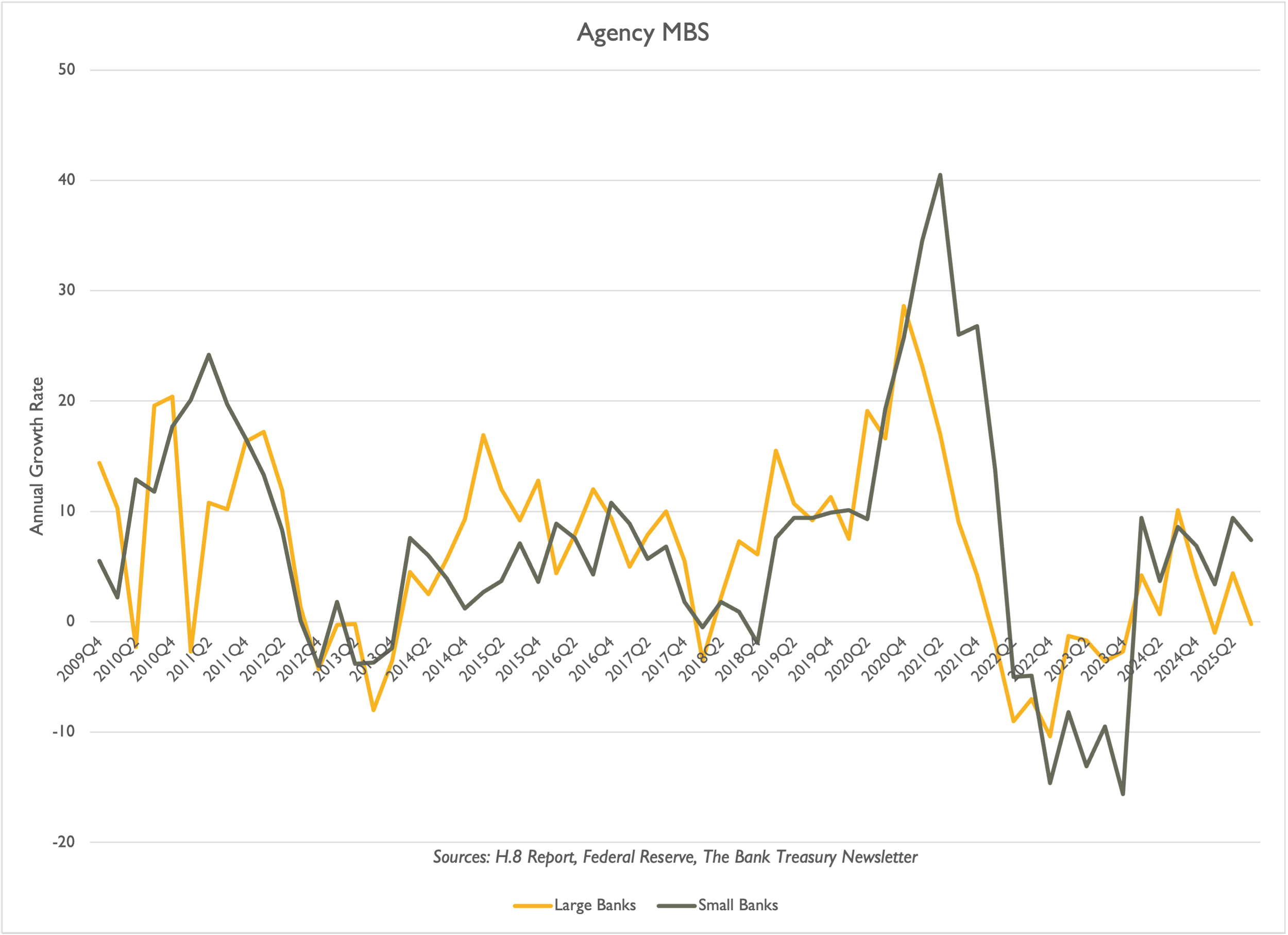

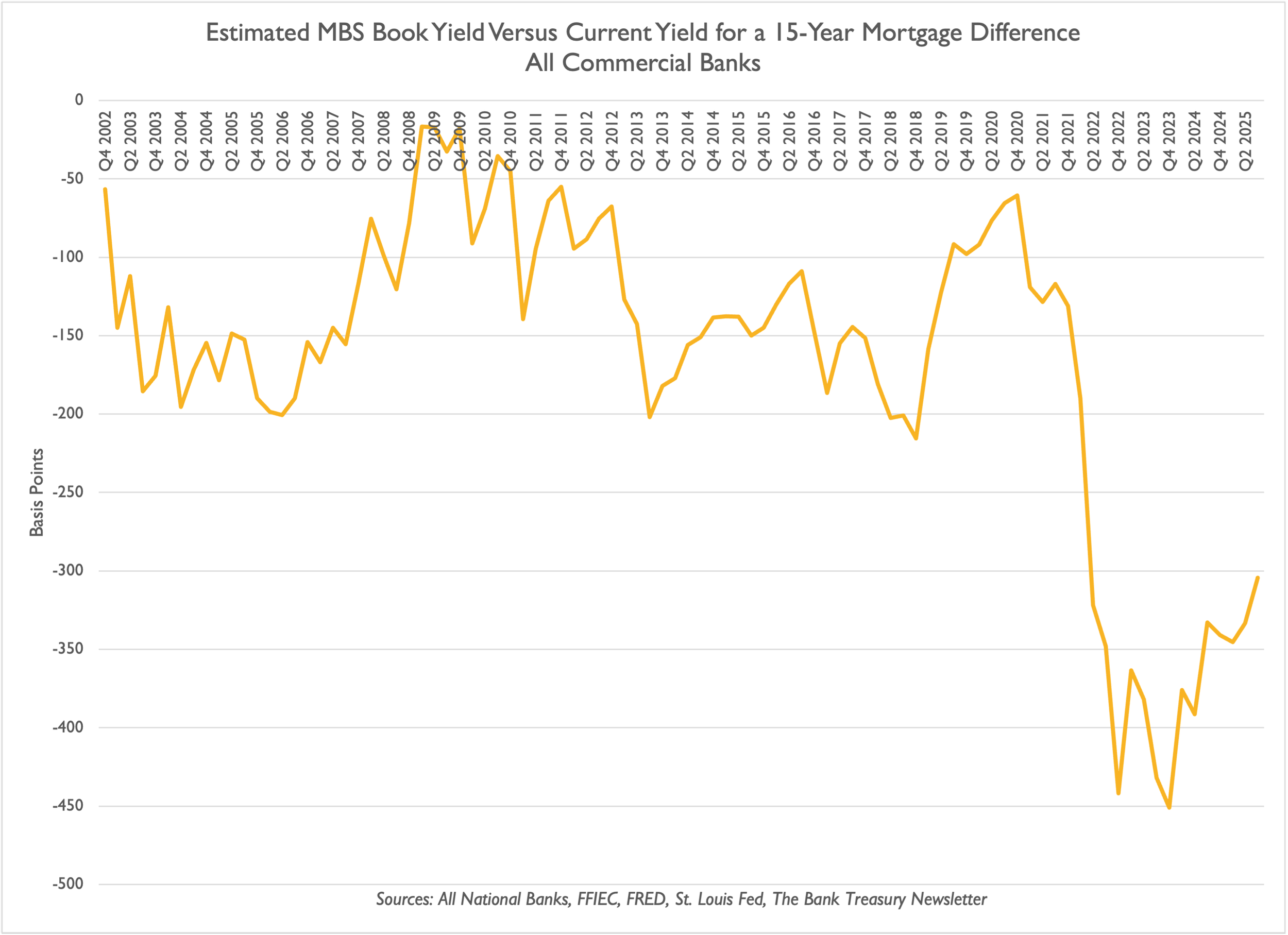

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac plan to buy up to $200 billion of outstanding Agency MBS this year to bring down 15- and 30-year mortgage rates, which currently stand at 5.6% and 6.0%, respectively. While large banks (H.8 definition) are ramping up purchases of Treasurys (Slide 2), small banks have been buying Agency MBS (Slide 3). Their book yield on their MBS portfolio remains well below the current coupons issued by the Agencies. The difference between a current coupon and the book yield in their portfolios is still 3 points (Slide 4).

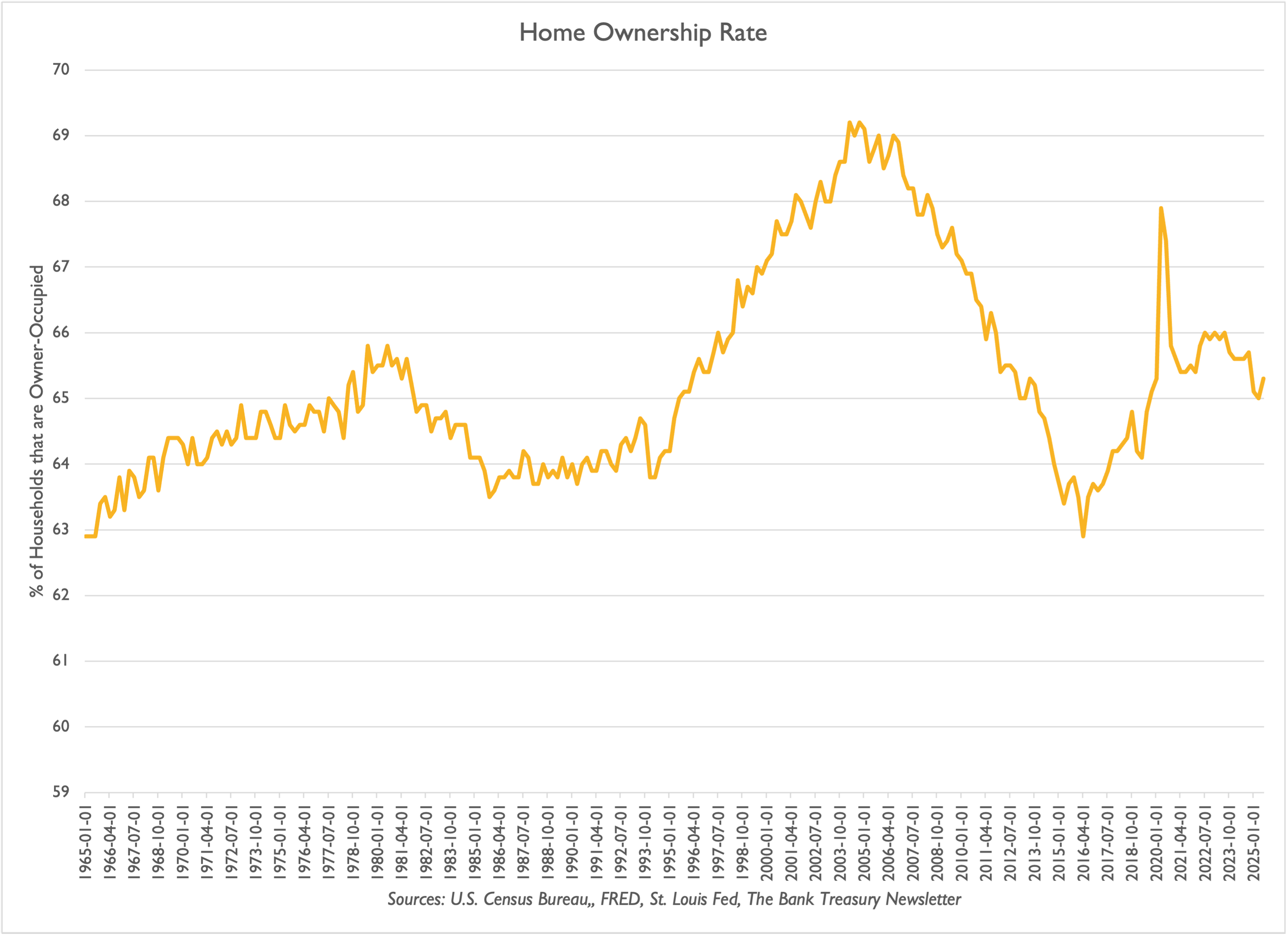

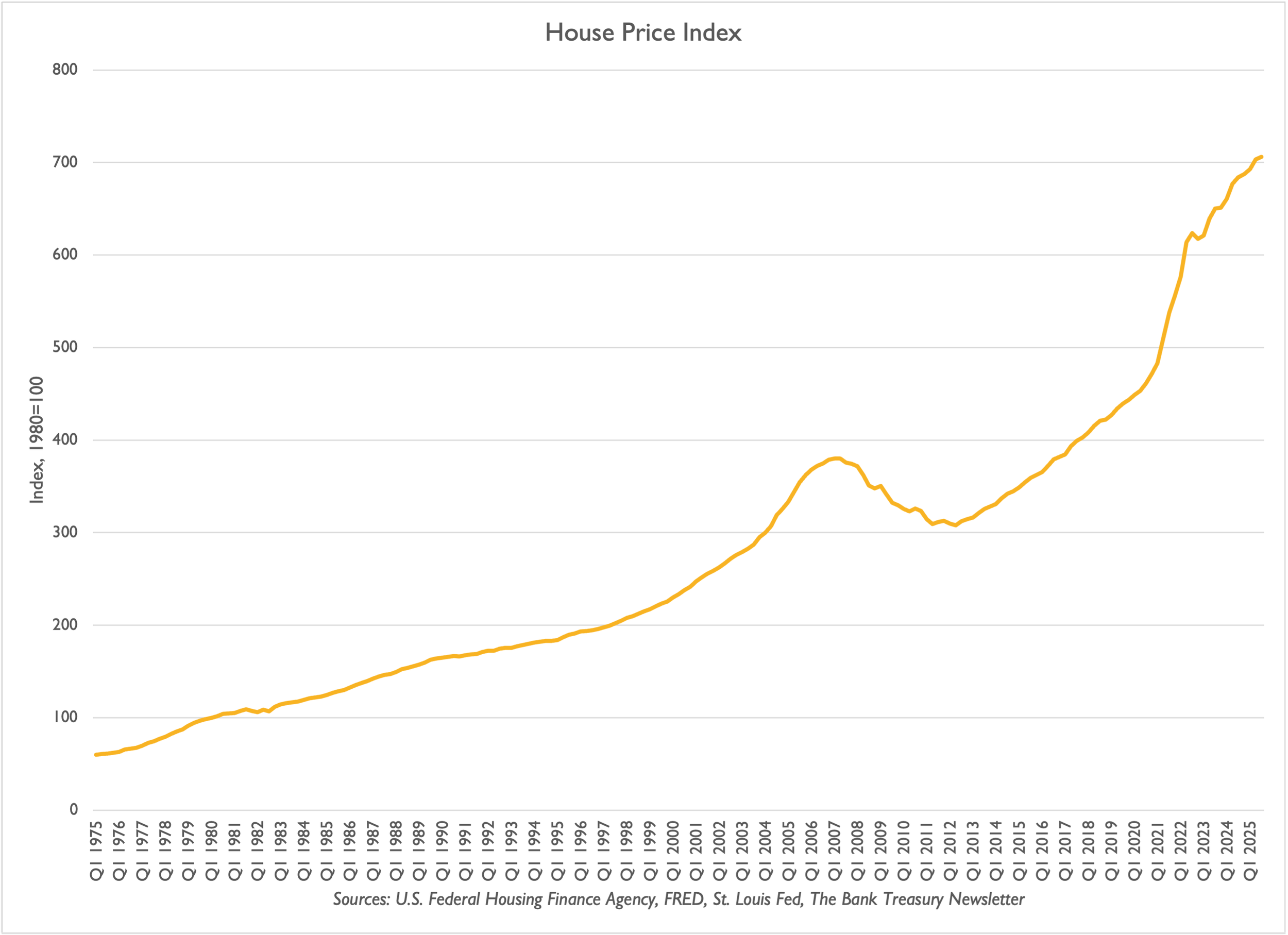

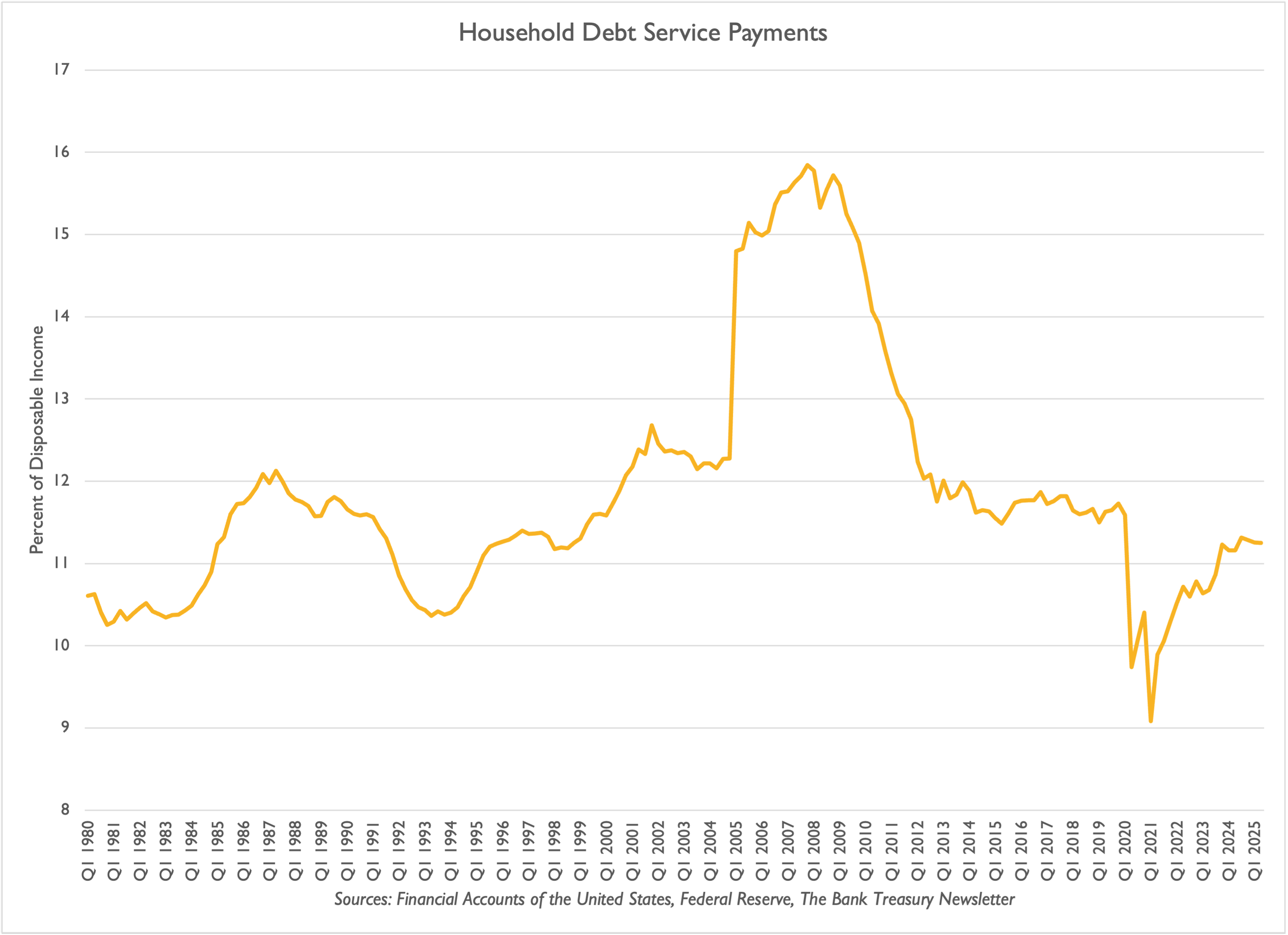

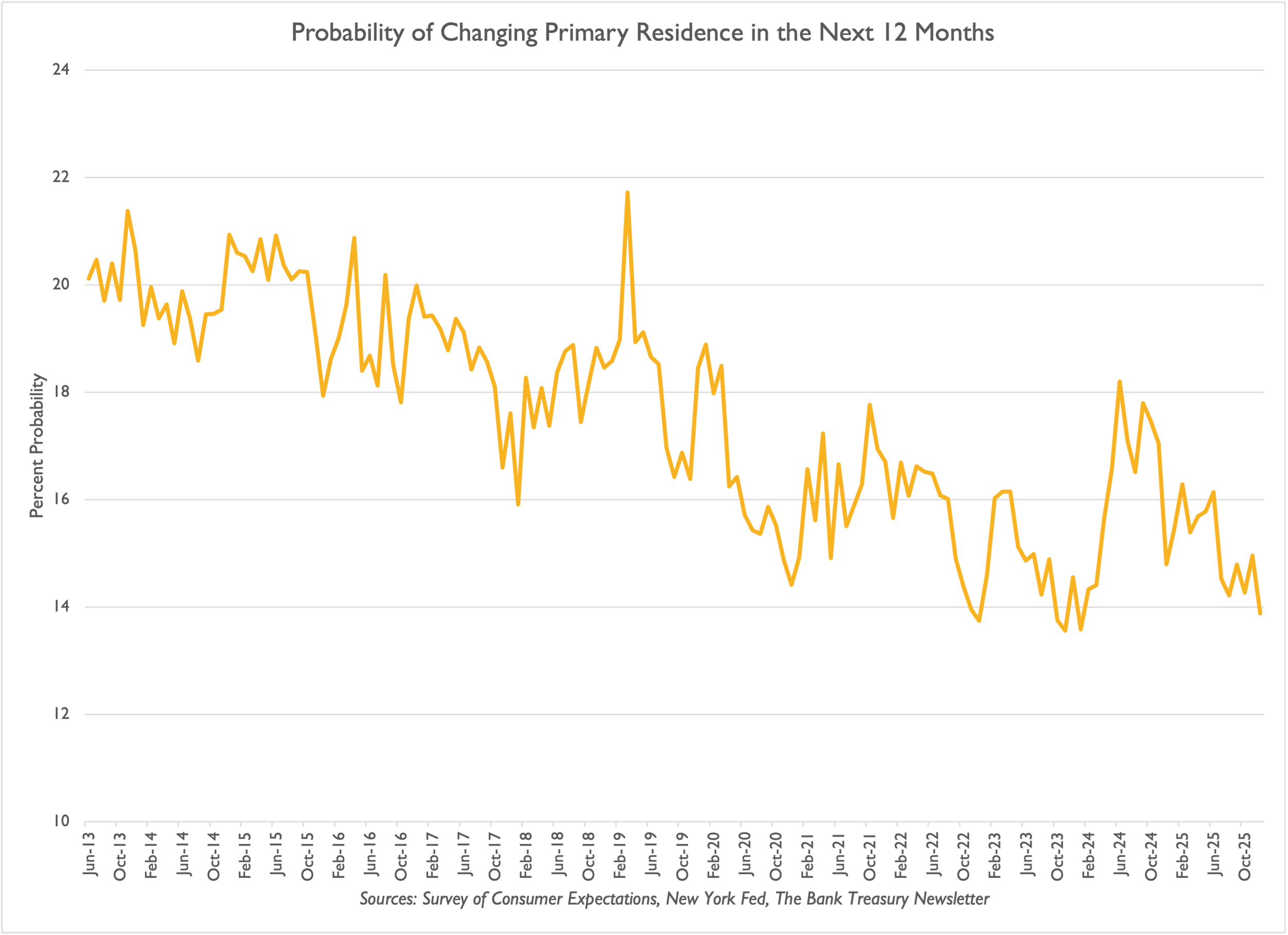

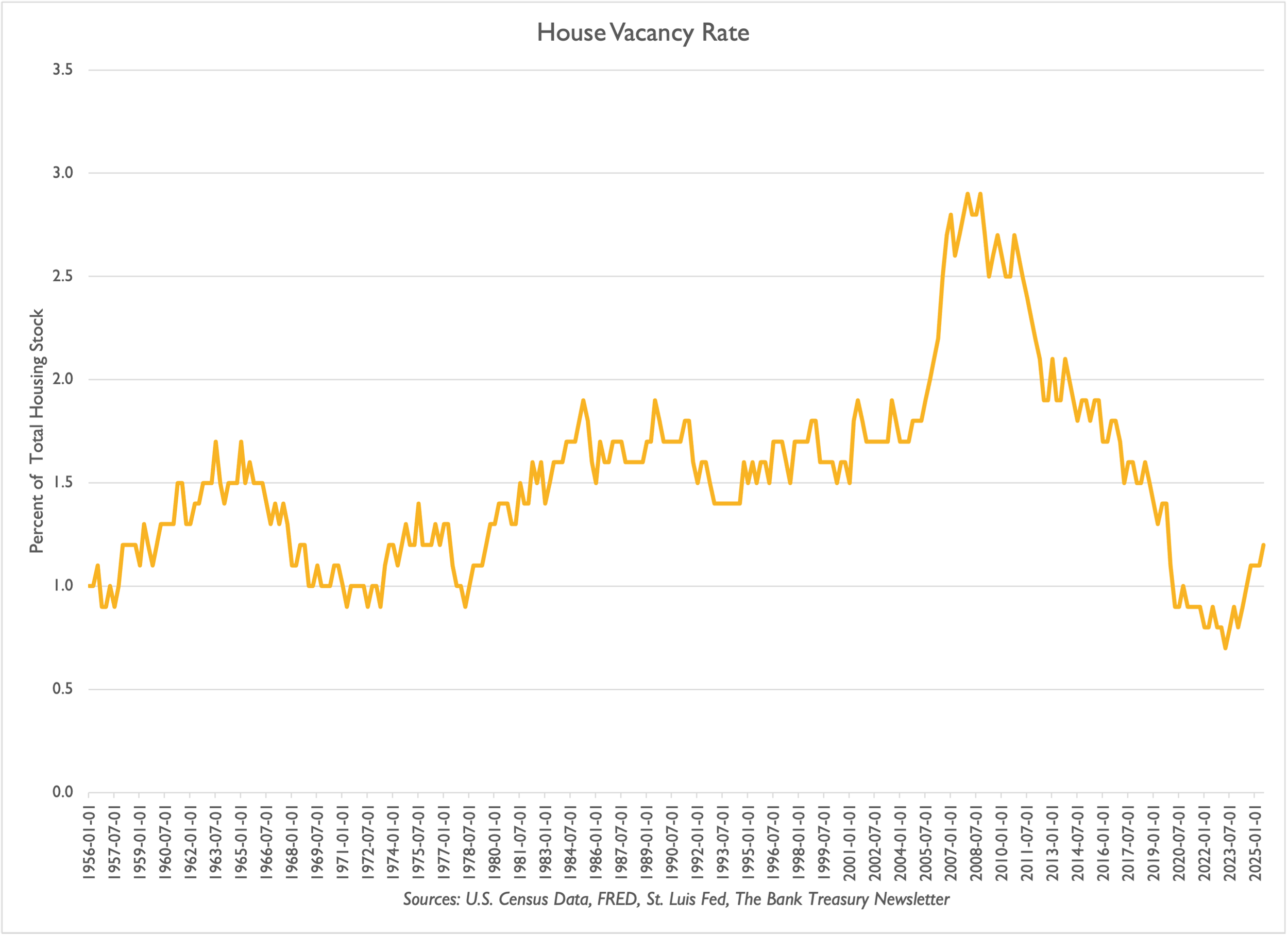

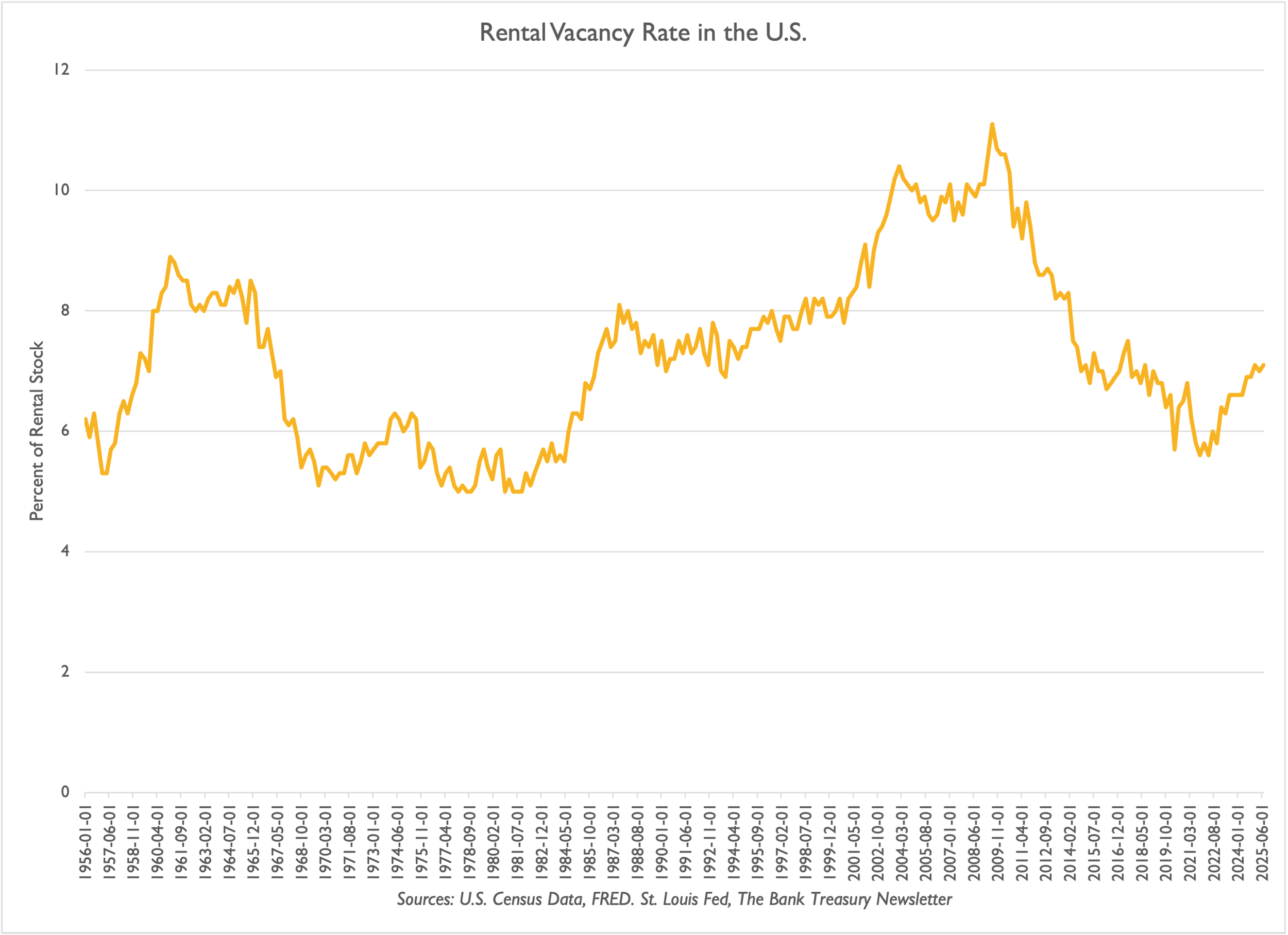

Fundamentally, the public’s demand for mortgage loans reflects a stagnating home-ownership trend (Slide 5), driven by soaring home prices (Slide 6). Sellers may also be less motivated than they have been, because paying a pandemic-era rate on their loans, they can afford to stay in their homes (Slide 7). They are also less likely to move than they have in years (Slide 8). Priced out of the market, the lack of first-time homebuyers is also contributing to the longer time it takes to sell a home (Slide 9) or even to rent an apartment (Slide 10).

Regulators Want To Lower The CBLR To 8%

Large Banks Are Buying Treasurys…

…While Small Banks Are Adding Agency MBS

Bond Portfolio Book Yields Are Still Underwater

Home Ownership Trends Are Stagnating

Home Prices Are Still Soaring

Homeowners Can Afford To Pay Their Mortgages

People Are Less Inclined To Move

It Is Taking Longer To Sell A Home

It Is Taking Longer To Rent An Apartment